While none of us want to contemplate our death, or that of our spouse, we all need an estate plan. If you need motivation to reach this decision, remember that every dollar you keep from the folks in Washington or your state capital goes to someone you like a heck of a lot better such as your kids, your younger sister, or your alma mater.

The term estate simply refers to the property owned by an individual. However, estate is more specifically defined as a separate legal entity holding title to the real and personal assets of a deceased person. Thus, estate accounting refers to the recording and reporting of financial events from the time of a person’s death until the ultimate distribution of all property the estate holds.

To ensure that this disposition is as intended and to avoid disputes, each individual should prepare a will, “a legal declaration of a person’s wishes as to the disposition of his or her property after death.” If an individual dies testate (having written a valid will), this document serves as the blueprint for settling the estate, disbursing all remaining assets, and appointing fiduciaries to accomplish these tasks.

When a person dies intestate (without a legal will), state laws control the administration of his or her estate. Although these legal rules vary from state to state, they normally correspond with the most common patterns of distribution. When inheritance laws rather than a will apply, real property is conveyed based on the laws of descent whereas personal property transfers are made according to the laws of distribution.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Each individual state establishes laws governing wills and estates known as probate laws. The National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws developed the Uniform Probate Code in hope of creating consistent treatment in this area.

To date, almost half of the states have officially adopted the Uniform Probate Code. In many of the other states, the rules and regulations applied are somewhat similar to those of the Uniform Probate Code. In practice, however, an accountant must become familiar with the specific laws of the state having jurisdiction over the estate of the specific decedent.

Administration of the Estate:

Regardless of the locale, probate laws generally are designed to achieve three goals:

1. Gather and preserve all of the decedent’s property.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Carry out an orderly and fair settlement of all debts.

3. Discover and implement the decedent’s intent for the remaining property held at death.

This process usually begins by filing a will with the probate court or indicating that no will has been discovered. If a will is presented, the probate court must rule on the document’s validity. A will must meet specific legal requirements to be accepted. These requirements may vary from state to state. For example, would the following signed and dated statement constitute a valid will?

“I want my children to have my money.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Because the writer is dead, the intention of this statement cannot be verified. Was this an idle wish made without thought, or did the decedent truly intend for this one sentence to constitute a will conveying all money to these specified individuals upon death? Did the decedent mean for all noncash assets to be liquidated with the proceeds being split among the children? Or did the writer strictly mean that just the cash on hand at the time of death should be transferred to them? Obviously, in some cases, a will’s validity (and intention) are not easily proven.

If deemed to be both authentic and valid, a will is admitted to probate, and the decedent’s specific intentions will be carried to conclusion. All of the decedent’s property must be located, debts paid, and distributions appropriately conveyed.

Whether a will is present or not, an estate administrator must be chosen to serve in a stewardship capacity. This individual serves in a fiduciary position and is responsible for- (1) satisfying all applicable laws and (2) making certain that the decedent’s wishes are achieved (if known and if possible).

If a specific person is named in the will to hold this position, the individual is referred to as the executor (executrix if female; this text will generically use the term executor) of the estate. If the will does not designate an executor or if the named person is unwilling or unable to serve in this capacity (or if the decedent dies without a will), the courts must select a representative.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A court-appointed individual is known legally as the administrator (female- administratrix) of the estate. An executor/administrator is not forced to serve in this role for free; that person is legally entitled to reasonable compensation for all services rendered.

The executor is normally responsible for fulfilling several tasks:

i. Taking possession of all of the decedent’s assets and inventorying this property.

ii. Discovering all claims against the decedent and settling these obligations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iii. Filing estate income tax returns, federal estate tax returns, and state inheritance or estate tax returns.

iv. Distributing property according to the provisions of the will (according to state laws if a valid will is not available) or according to court order if necessary.

v. Making a full accounting to the probate court to demonstrate that the executor has properly fulfilled the fiduciary responsibility.

Property Included in the Estate:

The basis for all estate accounting is the property the decedent held at death. These assets are used to settle claims and pay taxes. Any property that remains is distributed according to the decedent’s will (or applicable state intestacy laws). For estate-reporting purposes, all items are shown at fair value; the historical cost paid by the deceased individual is no longer relevant. Fair value is especially important because the sale of some or all properties may be required to obtain enough cash to satisfy claims against the estate. If valuation problems arise, hiring an appraiser could become necessary.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Normally, an estate includes assets such as these:

i. Cash.

ii. Investments in stocks and bonds.

iii. Interest accrued to the date of death.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iv. Dividends declared prior to death.

v. Investments in businesses.

vi. Unpaid wages.

vii. Accrued rents and royalties.

viii. Valuables such as paintings and jewelry.

At the time of death, the decedent legally owned a certain amount of assets. The executor’s task is to locate and value each item belonging to the estate as of that date.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Some state laws specify that real property such as land and buildings (and possibly certain types of personal property) be conveyed directly to the beneficiary or co-owner at the time of death, depending on the type of ownership held. Therefore, in these states, the inventory of the estate property that the executor develops for probate purposes does not include these assets. However, such items must still be listed in the filing of estate and inheritance tax returns because a legal transfer has occurred.

Discovery of Claims against the Decedent:

An adequate opportunity should be given to the decedent’s creditors to allow them to file claims against the estate. Usually, a public notice must be printed in an appropriate newspaper once a week for three weeks. In many states, all claims must be presented within four months of the first of these notices.

The executor must verify the validity of these claims and place them in order of priority. If insufficient funds are available, this ordering becomes quite important in establishing which parties receive payment. Consequently, claims in category 4 of the following list, most of which are paid before a beneficiary receives any assets, have the greatest chance of remaining unpaid.

1. Expenses of administering the estate. Without this preferential treatment, the appointment of an acceptable executor and the hiring of lawyers, accountants, and/or appraisers could become a difficult task in estates with limited funds.

2. Funeral expenses and the medical expenses of any last illness.

3. Debts and taxes given preference under federal and state laws.

4. All other claims.

Protection for Remaining Family Members:

A number of states have adopted the Uniform Probate Code. However, other states have passed a wide variety of individual probate laws that differ in many distinct ways. Thus, no absolute rules about probate laws can be listed. Normally, they provide some amount of protection for a surviving spouse and/or the decedent’s minor and dependent children.

Small monetary allowances are conveyed to these parties prior to the payment of legal claims. For example, a homestead allowance is provided to a surviving spouse and/or minor and dependent children. Even an estate heavily in debt would furnish some amount of financial relief for the members of the decedent’s immediate family.

In addition, these same individuals frequently receive a small family allowance during a limited period of time while the estate is being administered. Family members are also entitled to a limited amount of exempt property such as automobiles, furniture, and jewelry. All other property is included in the estate to pay claims and be distributed according to the decedent’s will or state inheritance laws.

Estate Distributions:

If a will has been located and probated, property remaining after all claims are settled is conveyed according to that document’s specifications. A gift of real property such as land or a building is referred to as a devise; a gift of personal property such as stocks or furniture is a legacy or a bequest.

A devise is frequently specific- “I leave 3 acres of land in Henrico County to my son,” or “I leave the apartment building on Monument Avenue to my niece.” Unless the estate is unable to pay all claims, a devise is simply conveyed to the intended party. However, if claims cannot be otherwise satisfied, the executor could be forced to sell or otherwise encumber the property despite the will’s intention.

In contrast, a legacy may take one of several forms. The identification of the type of legacy becomes especially important if the estate has insufficient resources to meet the specifications of the will.

A specific legacy is a gift of personal property that is directly identified. “I leave my collection of pocket watches to my son” is an example of a specific legacy because the property is named.

A demonstrative legacy is a cash gift made from a particular source. The statement “I leave $10,000 from my savings account in the First National Bank to my sister” is a demonstrative legacy because the source is identified. If the savings account does not hold $10,000 at the time of death, the beneficiary will receive the amount available. In addition, the decedent may specify alternative sources if sufficient funds are not available. Ultimately, any shortfall usually is considered a general legacy.

A general legacy is a cash gift whose source is undesignated. “I leave $8,000 in cash to my nephew” is a gift viewed as a general legacy.

A residual legacy is a gift of any remaining estate property. Thus, it is assets left after all claims, taxes, and other distributions are conveyed according to the residual provisions of the will. “The balance of my estate is to be divided evenly between my brother and the University of Notre Dame” is an example of a residual legacy.

An obvious problem arises if an estate does not hold enough funds to satisfy all legacies the will specified. The necessary reduction of the various gifts is referred to as the process of abatement.

For illustration purposes, assume that a will lists the following provisions:

I leave 1,000 shares of AT&T to my brother (a specific legacy).

I leave my savings account at Chase Bank of $20,000 to my sister (a demonstrative legacy).

I leave $40,000 cash to my son (a general legacy). I leave all remaining property to my daughter (a residual legacy).

Recording of the Transactions of an Estate:

The accounting process that the executor of an estate uses is quite unique. Because the probate court has given this individual responsibility over the assets of the estate, the accounting system is designed to demonstrate the proper management and distribution of these properties.

Thus, several features of estate accounting should be noted:

i. All estate assets are recorded at fair value to indicate the amount and extent of the executor’s accountability. Any assets subsequently discovered are disclosed separately so that these adjustments to the original estate value can be noted when reporting to the probate court. The ultimate disposition of all properties must be recorded to provide evidence that the executor’s fiduciary responsibility has been fulfilled.

ii. Debts, taxes, and other obligations are recorded only at the date of payment. In effect, the system is designed to monitor the disposition of assets. Thus, claims are relevant to the accounting process only at the time that the assets are disbursed. Likewise, distributions of legacies are not entered into the records until actually conveyed. Devises of real property are often transferred at death so that no accounting is necessary.

iii. Because of the importance of separately identifying income and principal transactions in many estates, the accounting system must always note whether income or principal is being affected. Quite frequently, the executor maintains two cash balances to assist in this process.

To illustrate, assume that James T. Wilson dies on April 1, 2008.

The following valid will has these provisions:

I name Bob King as executor of my estate.

I leave my house, furnishings, and artwork to my aunt, Ann Wilson.

I leave my investments in stocks to my uncle, Jack E. Wilson.

I leave my automobile and personal effects to my grandmother, Nancy Wilson.

I leave $38,000 in cash to my brother, Brian Wilson.

I leave any income earned on my estate to my niece, Karen Wilson.

All remaining property is to be placed in trust for my children.

The executor must- (1) perform a search to discover all estate assets and (2) allow an adequate opportunity for every possible claim to be filed. The assets should be recorded immediately at fair value with the creation of the Estate Principal account. This total represents the amount of assets for which the executor is initially accountable.

The following journal entry establishes the values for the assets owned by James T. Wilson at his death that have been found to date:

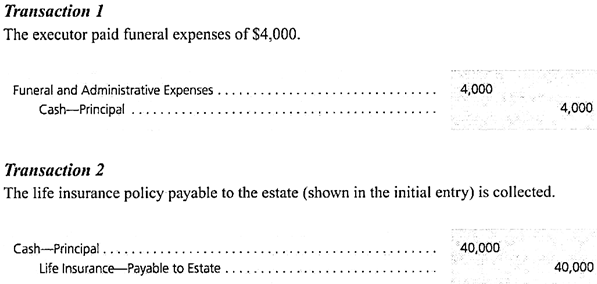

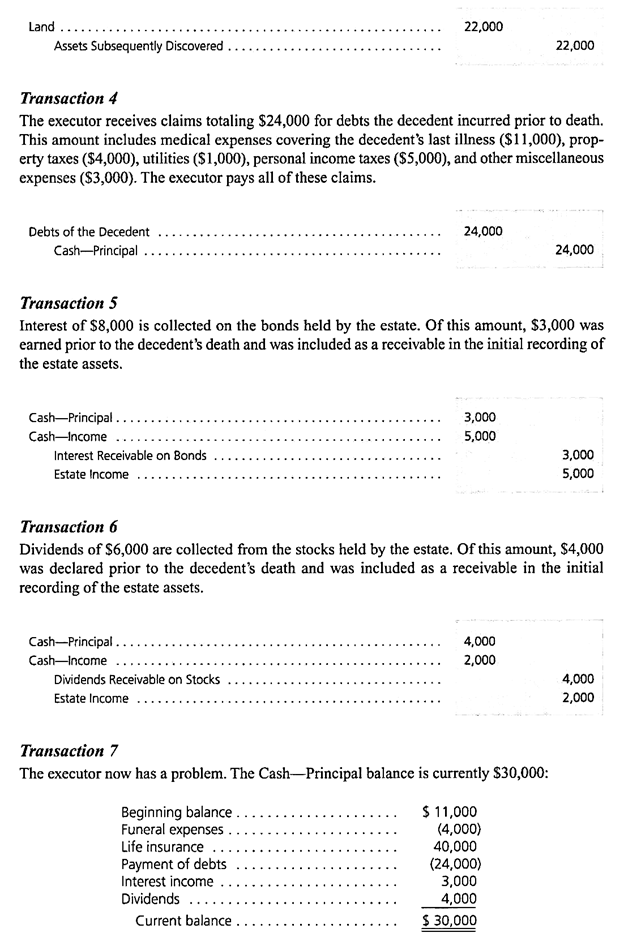

Following is a list of subsequent transactions incurred by this estate with each appropriate journal entry. Because estate income is to be conveyed to one party (Karen Wilson) but the remaining principal is to be placed in trust, careful distinction between these two elements is necessary.

However, the decedent bequeathed his brother, Brian Wilson, $38,000 in cash. This general legacy cannot be fulfilled without selling some property. Most assets have been promised as specific legacies and cannot, therefore, be used to satisfy a general legacy. Two assets, though, are residual- the investment in bonds and the land that was discovered. The executor must sell enough of these properties to generate the remaining funding needed for the $38,000 conveyance.

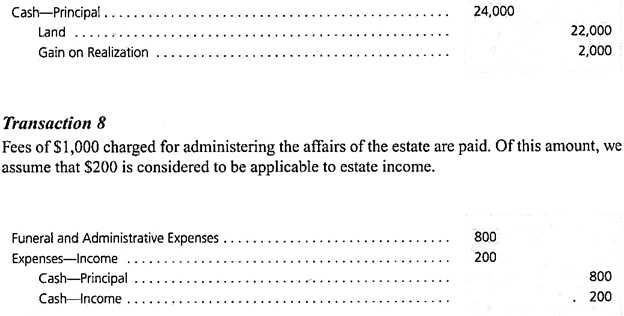

In this illustration, assume that the executor chooses to dispose of the land and negotiates a price of $24,000. Because a principal asset is being sold, the extra $2,000 received above the recorded value is considered an adjustment to principal rather than an increase in income.

Charge and Discharge Statement:

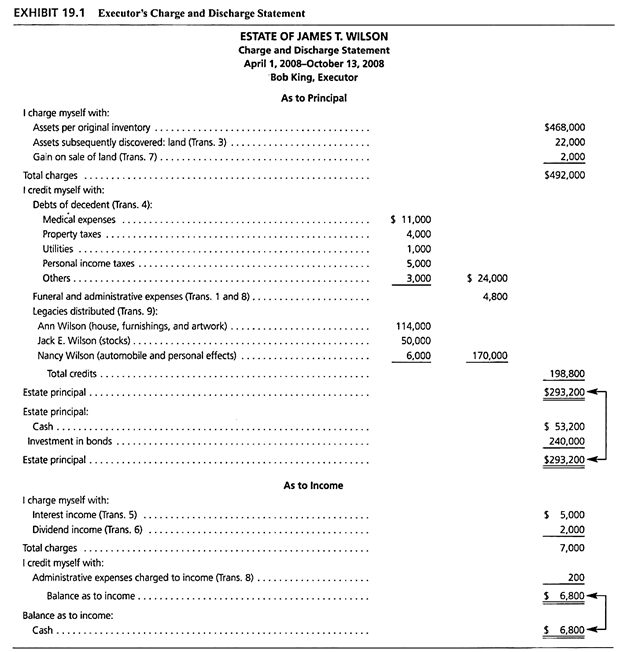

As necessary, the executor files periodic reports with the probate court to disclose the progress being made in settling the estate. This report, which may vary from state to state, is generally referred to as a charge and discharge statement. If income and principal must be accounted for separately, the statement is prepared in two parts.

For both principal and income, the statement should indicate the following:

1. The assets under the executor’s control.

2. Disbursements made to date.

3. Any property still remaining.

Thus, the executor of James T. Wilson’s estate can produce Exhibit 19.1 immediately after Transaction 9. (Transaction numbers are included in parentheses for clarification purposes.)

At this point in the illustration, only three transactions remain- distribution of the $38,000 cash to the decedent’s brother, conveyance of the $6,800 cash generated as income since death to the niece, and establishment of the trust fund with the remaining principal. The trust fund will receive the $240,000 in bonds and the $15,200 in cash that is left in principal ($53,200 total less $38,000 paid to the brother).

The executor would then prepare a final charge and discharge statement and then closing entries to signal the conclusion of the estate as a reporting entity.