The three major categories of methods used to establish product prices are cost-oriented pricing, competition-oriented pricing, and demand-oriented pricing.

A retailer may use one or a combination of the methods. The most common is cost-oriented pricing. A number of methods are prevailed for determination of the products price.

Price is the only element of the marketing mix that produces revenue; other elements produce cost. Prices are the easiest marketing mix element to adjust.

Price also communicates to the market about the company intended value propositioning of its product or brand. Various methods may be adopted to arrive at the international price of different commodities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Some of the pricing methods in marketing are:

A. Cost-Oriented Pricing: 1. Mark-up Pricing 2. Break-Even Pricing 3. Target-Return Pricing

B. Competition-Oriented Pricing

C. Demand-Oriented Pricing: 1. Modified Breakeven Pricing 2. Consumer Market Pricing 3. Industrial Market Pricing.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

D. Market-Oriented Pricing: 1. Perceived-Value Pricing 2. Going-Rate Pricing.

E. Pricing Methods Based on Cost: 1. Cost plus Pricing Method 2. Marginal Cost or Incremental Cost Pricing Method 3. Breakeven Point Pricing Method 4. Pricing Method Based on Rate of Return.

F. Pricing Methods Based on Market Conditions: 1. Pricing at Market Price Level or Going Rate Pricing 2. Pricing below Competitive Level 3. Pricing above Competitive Level 4. Purchasing Power Pricing.

G. Some of the other methods of pricing are: 1. Price Leadership 2. Transfer Pricing 3. Going Rate Pricing 4. Product Tailoring 5. Refusal Pricing 6. Product-Line Pricing 7. Cyclical Pricing 8. Peak-Load Pricing.

Pricing Methods: Cost-oriented, Competition-oriented and Demand-oriented Methods

Pricing Methods in Marketing – 3 Important Methods (With Formula)

The three major categories of methods used to establish product prices are cost-oriented pricing, competition-oriented pricing, and demand-oriented pricing. A retailer may use one or a combination of the methods. The most common is cost-oriented pricing.

Method # 1. Cost-Oriented Pricing:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To generate a profit, product costs must be covered. Cost-oriented pricing (also called cost-plus pricing) has two approaches – mark-up pricing (the more common) and breakeven pricing. The retailer needs to determine its mark-up percentage; one way to do this is to look at traditional product mark-ups within the industry and at the manufacturer’s suggested retail price.

The retailer must also consider the product’s average turnover, the amount of competition for the product, the levels of service required, and the amount of sales time and effort involved in selling the product. All these factors, along with the inclusion of the expected or targeted profit margin, determine the mark-up.

(a) Mark-up Pricing:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In mark-up pricing, two options exist for determining the mark-up percentage: mark-up based on the retail, or selling, price of the product, and mark-up based on the product’s cost. The chosen method is generally selected based on the accounting systems the retailer employs. The vast majority of retailers use mark-up based on selling price, because expenses and profits for the product’s sales are calculated as a percentage of sales.

In addition, this method keeps the mark-up percentage from exceeding 100 percent. Manufacturers and other suppliers most often quote discounts and price reductions from the retail selling prices they provide to the retailer. Finally, retail sales information is easier to acquire than cost information is; thus, it is easier to compare sales to those of competitors (and other stores) than it is to compare costs.

The general formula for developing a mark-up based on the retail price of the product is as follows:

Amount of mark-up = Selling price (retail price) – Cost If a product’s selling price is $ 100 and the cost is $40, the mark-up is calculated as $100 – $40 = $60. To calculate the mark-up percentage, use this formula –

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Mark-up percentage = Amount of mark-up/Selling price Using the example above, the percentage mark-up at retail would be $60/ $100, or 60 percent.

To calculate the selling price rather than the cost, use the following formula:

The product’s cost can also be calculated. Consider the following example. A product’s selling price is $50 and the mark-up percentage, based on cost, is 65 percent, if SP = C + M, then SPI (I + mark-up) will give the cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Let’s calculate this problem using both methods:

Keep in mind that the cost of goods equals the cost, per unit, of the merchandise (invoice price) plus the inbound freight costs associated with getting the merchandise. In addition, any discounts received from the trade as part of a purchase (including quantity discounts) are also taken out.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Break-Even Pricing:

Breakeven pricing is the other method used in the creation of a cost-oriented pricing system. With breakeven pricing, the retailer determines the breakeven point (BEP), or the level of sales needed to cover all the costs associated with selling the product.

The breakeven point is calculated using the following formula:

BEP (in quantity) = Fixed cost/Unit price – Unit variable cost

This formula can be modified to calculate the BEP in dollars by multiplying the BEP (in quantity) by the selling price of the item.

Method # 2. Competition-Oriented Pricing:

In competition-oriented pricing, the retailer identifies the industry leader and then replicates the leader’s prices. In using this method, the retailer assumes that the industry leader is best equipped to select appropriate price levels for its products.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Retailers often ‘shop’ the corn petition to ascertain competitors’ price structures. A representative from the retailer’s organisation visits a competitor’s store to see what prices are set for the product mix. Shopping the competition is not always welcomed by retailing competitors, especially when done in person.

It is understood that environmental scanning should be an on-going, not sporadic process, however, so many retailers see these actions as necessary. Particularly in service retailing, the same information often can be obtained from phone calls to competitors.

For example, a large hotel chain in southern Colorado regularly has disguised ‘shoppers’ call competing hotels and ask for list of prices for the various rooms. Different rates, such as state rates, government rates, AAA rates, and frequent-traveller rates, are checked. The chain then adjusts its prices based on the competitor’s rates.

If competitors raise or lower their prices, the retailer follows suit with price increases or decreases. Competition-oriented pricing assumes that costs, demand, competition, and other factors external to the retail firm remain fairly constant. Therefore, it is safe to follow the leader or follow the general trends within the industry.

Method # 3. Demand-Oriented Pricing:

Under the demand-oriented pricing method, prices are set based on consumer demand. In this approach, retailers often raise prices based on unusual environmental changes. These changes might include unusually-high customer demand (e.g., for fad products), events such as natural disasters, of conflicts in other countries that affect supplies of various products such as gas or oil.

In some instances, retailers raise their prices to exorbitantly high levels, a tactic called price gouging. Although this tactic may appear to be a sound business practice, it is an ethical grey area. Customers may pay the demanded price initially, but they may harbour negative feelings toward the retailer, thus decreasing long-term business and goodwill.

The three major types of demand-oriented pricing are:

(i) Modified breakeven,

(ii) Consumer market and

(iii) Industrial market pricing.

(i) Modified Breakeven Pricing:

Modified breakeven pricing assumes the retailer estimates the market demand for the product and then applies it to the breakeven point. In so doing, the retailer can estimate, or forecast, sales at different price points or levels.

(ii) Consumer Market Pricing:

When using a consumer market approach to pricing, the retailer generates data about prices based on controlled store experimentation. Many techniques can be applied here, but the general idea is that consumers enter the store and are allowed to make product purchases. The prices on the various products are changed, and the retail researcher tracks the price points that are most popular with the consumers. The retailer then implements these price points throughout its locations.

(iii) Industrial Markets Pricing:

A technique much like the consumer market approach is the industrial market approach. With this approach, the retailer sells its products to other businesses in addition to the final consumer. The retailer performs a wholesaling function aimed toward other businesses.

If the retailer is reselling products to intermediaries or industries (such as Home Depot, Office Depot, or Office Max may do), the retailer identifies the benefits of its products compared to competitors’ products and sets prices accordingly.

The assumption is that industrial buyers do not buy as much on emotion as ultimate consumers do. Rather, industrial buyers, or intermediary buyers, purchase more on a need basis. Consequently, by identifying the benefits these buyers are seeking, the retailer is better able to set price. This technique is also used when responding to government bids; in this situation, the government agency purchasing products is treated like another business.

Once product and service prices have been set, retailers need to prepare for the possibility that they will not sell all the products at the established prices.

Retailers must develop initial markups, maintained markups, and gross profit margin projections for the store inventory. In addition, retailers must consider creating markdowns for products, to move slower-selling items off the shelves. We will look at how an initial markup percentage is developed.

The initial markup percentage is a starting point for setting individual product prices. After calculating an initial markup percentage, the retailer can calculate the impact of markups, markdowns, and discounts. Initial markup percentages are usually calculated based on the retail selling price. Initial markups are calculated by taking the estimated retail expenses, adding them to the planned retail profit, and adding that figure to the planned reductions.

This figure is then divided by the planned net sales plus the retail reductions:

The markup is based on the original retail values placed on the merchandise after subtracting out the costs associated with the merchandise. By looking at the actual prices the retailer paid for the merchandise and again subtracting out the costs associated with that merchandise, the retailer can calculate its maintained mark-up percentage –

Another method is to take the average retail prices of products and then subtract out the costs associated with the merchandise and divide by the average retail price:

Finally, the retailer may want to know what its gross margin will look like. The gross margin is the total cost of goods sold (COGS) for the retailer subtracted from the retailer’s net sales:

Gross Margin in Dollars= Net Sales – COGS

Gross margin allows the retailer to adjust for cash discounts and other expenses associated with sales of goods and, services. The retailer may still have to adjust the prices on some merchandise. The process of changing prices is called price adjustment.

Variables in the Initial Mark-up Percentage:

Variables in the initial mark-up percentage can affect the initial price. One variable is the influence members of the retailer’s channel of distribution can have on the organisation. In distributor relationships, members of the channel of distribution have expectations of the other channel members. One expectation may be that the retailer adheres to the manufacturer’s suggested retail price.

The amount of influence a given channel member has is based on the type of supply chain used and the dominance of the channel member. For example, because Wal-Mart purchases in very large quantities, its suppliers give the discounter a smaller mark-up than they would give other retailers that purchase less. Wal-Mart then passes on those savings to its customers, thus creating a competitive advantage.

Related to the influence of channel members are the variables of quantity discounts and shipping arrangements. These variables are negotiated with suppliers and consequently have an impact on the price the retailer sets. In their infancy, e-tailers got into trouble by failing to factor in the shipping and handling costs associated with retailing products to end users. This was one of the significant factors that contributed to the failure of a number of dot-com companies.

Pricing for cyberspace sales can be a difficult task. Although e-tailers have an advantage over brick-and-mortar businesses in that they have lower physical location expenses and a less labour-intensive environment, in other ways they are at a disadvantage – customers can access the prices of competitors with the click of a button’s. Thus, e-tailers should avoid using price as a main tactic in attracting customers. They should also stay away from price wars with well- established retail outlets that have deeper pockets than they do.

Pricing Methods in Marketing – Top 2 Methods

A number of methods are prevailed for determination of the products price.

The different methods of price determination can be classified in two divisions for the sake of convenient study:

(1) Pricing Methods based on cost, and

(2) Pricing Method based on market conditions.

A brief description may be made on this topic as under:

1. Pricing Methods Based on Cost:

The cost of product is inseparable part of price. Hence, one should do study in depth on fixed costs, variable cost, total costs, average costs and marginal costs etc.

Several methods of price determinations on basis of cost are as under:

i. Cost plus Pricing Method:

It is a simplest and ideal method for price determination. The price of a product is determined by adding desirable profit with total cost per unit of product.

It is determined by using the following formula:

Per Unit Price = (Total Cost / No. of units) + (Total estimated profit / No. of units)

Per unit price = Per unit total cost + Per unit desired profit.

The quantum of total estimated profit depends on the necessity of commercial undertaking. Some commercial undertakings determine the product price by adding a certain percentage of profit with total cost per unit of product under this method.

For example-

Price per unit = Total cost per unit + 15% of the cost.

This method can be adopted only when there are no competitors in the market or per unit total cost of product for all competitors is uniform and when they want to yield profit in uniform rate viz., there should be no differential price fixed by competitors in the market. However, it seems impracticable. Services of public utility like – train and road transport, water, electric power provided by the government undertaking exercise this method.

ii. Marginal Cost or Incremental Cost Pricing Method:

Price of a product under this method is determined on the basis of marginal cost or incremental cost. In other words, the price of product equal to per unit changing cost is determined under this method.

This method is often used for entering into market at the initial stage or maintaining the employment of labourers in recession and for continuing the work. Any commercial undertaking cannot use this method for a longer period because the commercial undertaking has to bear certain stable costs coincide the changing costs and requires earning profit in much or less quantum.

iii. Breakeven Point Pricing Method:

Even point pricing method is purported to such quantum of a product at which total cost of production becomes equal to total sales revenue viz., there occurs no profit no loss at that quantum. This method therefore, is called no profit no loss pricing method.

This method is based on assumption that stable cost remains stable in combination and the variable cost per unit remains stable and the business undertaking has to adopt market price. The business undertaking therefore, should do production at least in the quantum in which total cost of undertaking becomes equal to total sales proceeds.

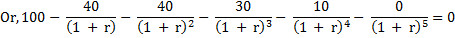

The break-even point is the point where the total revenue (TR) is just equals total cost (TC), which can be founded by using the following formula –

Break-even Point (in units) = Total Fixed Cost / Selling Price – Variable Cost

This method can be adopted only when the industry is suffering from recession or there is an acute competition in the market of any special order is to meet on the basis of total cost.

iv. Pricing Method Based on Rate of Return:

The desired profit is computed at the certain rate of consideration for a certain period of time on the capital invested in the undertaking. The desired profit is then added with the total cost of that period and price per unit is determined.

This method is exercised in order to receive a certain consideration on the capital invested in the commercial undertaking. This method is impractical in the state of competition.

2. Pricing Methods Based on Market Conditions:

The price of a product should be determined by keeping in mind the market conditions otherwise the production may face failures.

A brief description on the methods of determination of price can be made as under:

i. Pricing at Market Price Level or Going Rate Pricing:

The business undertaking follows the prevailing competitive prices in the market for determination of its product price under this method.

This method is adopted only when there is existed a perfect competition in the market and there is no difference between the products of commercial undertaking and that of the products of competitors. This method is adopted for the price determination of bidis, toffees, Kulfis etc., in India. This method is known as customer pricing method too.

ii. Pricing below Competitive Level:

The price of product are determined a little less than the price of competitive products existing in the market. This method is more useful for such commercial undertakings whose products are in the initial stage or who want to enter into new markets or who are inclined to show them as price leader in the market.

iii. Pricing above Competitive Level:

The price of product is determined a little high than the price of competitive products in the market. This method is useful for such commercial undertakings who has acquired much popularity in the market or who want to prove their product as product of the best category. Hindustan Lever Ltd., Mumbai has fixed more price for its Dalda Vanaspati as compared to other manufacturers of this product.

iv. Purchasing Power Pricing:

Some commercial undertakings determine the product price by keeping in mind the purchasing parity of their consumers. This method is generally used for determination of the price for fashionable products.

A number of methods for price determination have their own advantages and disadvantages thus, raising a question that which method is the best out of them? Answer to this question is not possible without a proper study on the objectives of commercial undertaking, the characteristics of its product and the circumstances prevailing in the market.

It can only be said that prices should be determined with such method that can give desired profit to the undertaking. Completion is faced, safe-guard the interests of middlemen ensured and the consumers may thus, receive satisfaction.

Pricing Methods in Marketing – Cost-Oriented and Market-Oriented Methods (With Advantages and Disadvantages)

Price is the only element of the marketing mix that produces revenue; other elements produce cost. Prices are the easiest marketing mix element to adjust. Price also communicates to the market about the company intended value propositioning of its product or brand.

“Price is the cost that a customer pays for the product; it is the only element of the marketing mix which generates the revenue.” – ‘Philip Kotler’

Price is one of the most important elements of the marketing mix.

Various pricing methods are given as under:

1. Cost-Oriented Methods:

With this approach of pricing the price of the product is set on the basis of the total cost of the marketing of the product.

Following methods are the cost oriented methods:

(a) Mark-up Pricing:

The mark-up pricing method is used to add a standard mark-up (profit margin) to the product cost, using following formula –

Unit Cost = V.C. + (F.C./unit sales)

Mark-up Price = Unit Cost/ (1- desired return on sales)

Advantages:

i. Easy to calculate.

ii. Easy to implement.

Disadvantages:

It ignores the current demand, perceived value and competition.

(b) Target-Return Pricing:

With this approach of calculating price, the firm determines the price that would yield its target rate of return on investment (ROI), using following formula-

Target Return Price= unit cost + (desired return x invested capital)/ unit sales

Advantages:

i. Easy to calculate.

ii. Easy to implement.

iii. It covers the return on investment.

Disadvantages:

It ignores the current demand, perceived value and competition.

2. Market-Oriented Methods:

With this the market price is used to as a base to calculate the price of the product.

Following methods are the market-oriented methods:

a. Perceived-Value Pricing:

With this approach the price of the product is set on the basis of the customer’s perception about the product value.

The perceived value is made up of several elements such as:

(a) Buyer’s image of product performance

(b) The channel deliverables

(c) The warranty quality

(d) Customer support

(e) Supplier’s reputation.

b. Going-Rate Pricing:

With this approach the benchmark for setting prices is the price set by major competitors. If a major competitor changes its price, then the smaller firms may also change their price irrespective of their costs or demand.

The going-rate pricing can be further divided into three sub-methods:

(a) Competitors ‘parity method – A firm may set the same price as that of the major competitor.

(b) Premium pricing – A firm may charge a little higher if its products have some additional special features as compared to major competitors.

(c) Discount pricing – A firm may charge a little lower price if its products lack certain features as compared to major competitors.

Price is one of the most important and crucial factors of the marketing mix elements. Any changes in price should be justified with quality of the product in order to maintain the positive value of the product.

Pricing Methods in Marketing – (With Merits and Demerits)

Various methods may be adopted to arrive at the international price of different commodities.

Method # 1. Cost-Oriented Export Pricing:

a. Cost Plus Pricing or Full Cost Method:

Cost plus pricing, also known as full cost approach or markup pricing is a common method of pricing. In this method the price includes a certain percentage of profit margin on the sum total of the full cost of production, marketing costs and an allocation of the overheads i.e. A firm aims at in the export business to earn a reasonable profit and tries to recover the entire production cost incurred by it. Under this approach, the average total cost of each unit of output is computed and then a desired profit mark-up is added to it to arrive at the price, i.e.

The merits of the cost plus approach are:

(i) It covers all costs and leads to fairly stable prices.

(ii) It is designed to provide the target rate of margin.

(iii) It is a rational method and widely accepted.

(iv) It is a simple method.

The cost plus pricing has several demerits which are given below:

(i) The cost calculations are based on a predetermined level of activity.

(ii) It brings an element of inflexibility in the pricing decision.

(iii) It ignores the price elasticity of demand.

(iv) Another drawback is that sometimes opportunity to charge a high price is forgone.

(v) The term cost and its calculation may be quite difficult.

(vi) The cost-based pricing would not be helpful for some of the objectives or tasks like market penetration, fighting competition etc.

b. Marginal Cost Pricing:

Pricing on marginal cost basis means that the prices should be so set that at least the marginal cost (MC) or variable cost is covered. Generally, the Total Cost (TC) is divided into two categories, Fixed Costs (FC) and Variable Cost (VC).

TC = FC + VC

Fixed costs remain unchanged irrespective of the volume of output e.g. plant and machinery, building, lighting etc. whereas variable cost vary in proportion to the volume of production e.g. raw material costs, labour costs, fuel and power etc. Thus, under marginal cost pricing method the relevant costs are the variable costs.

The marginal cost approach implies that prices of export goods should be so fixed that atleast the variable costs are recovered. The underlying assumption here is that the fixed costs of production are recoverable from the domestic sale and hence need not be included in export prices.

Thus in export operations, profitability has to be assessed not in relation to average costs but with reference to marginal costs which should generally constitute the basis for export pricing. Fixed cost is excluded from the calculation of the cost of the product.

The principle of marginal cost pricing is generally applicable to situations where:

1. There is excess capacity in the manufacturing units.

2. The major share of the production is not exported.

3. The price in the domestic market can be so adjusted as to cover the fixed costs.

When excess capacity exists, the marginal costs indicate the lower limit up to which a firm can bring down its price without affecting its overall profitability. In other words, an order which may appear to be unprofitable and therefore unacceptable because of adopting the full cost approach (i.e. both fixed cost + variable costs) may appear to be profitable if marginal cost approach its adopted.

The use of marginal costing method can be illustrated with an example.

Example:

Suppose a company with a production capacity of 40,000 units per year, is presently producing and selling 30,000 units a year at a price of Rs.15 per unit is the domestic market.

Further suppose the cost structure is as shown below:

Now suppose the company has an opportunity to sell an additional 6,000 units at Rs.10 per unit to a foreign firm. If the company uses the marginal costing approach to make decisions, then the offer would be accepted since the firm’s marginal cost is only Rs.9, it would gain a profit of Rs. (6000 × 1/-)= Rs.6,000 if it undertakes to export. On the other hand an export price lower than the marginal cost of Rs.9 will not be profitable therefore not acceptable to the firms.

Following are the main advantages of marginal cost pricing:

(i) When idle capacity exists marginal costing is a realistic approach to evaluating an export order.

(ii) Marginal cost pricing will make the firms more price competitive.

(iii) It may help the firm in market penetration.

(iv) It may help the firm to increase its total sales turnover.

(v) It is more realistic in nature.

(vi) It is useful for the products of developing countries. In many of these countries price is still the decisive factor and quality is comparatively less important. Low prices may serve to widen and create markets. High prices may limit the sales to a small segment of the market.

These are certain drawbacks of marginal cost pricing which are:

(i) Once the importers become used to low prices it may be difficult to increase prices later on.

(ii) It is applicable and useful in short run, not in long run.

(iii) It is advisable only when idle capacity with no opportunity cost exists.

(iv) Exporters may undercut each other and this leads to an unnecessary loss of foreign exchange.

(v) Low prices may be quoted on the basis of marginal costs even where foreign markets may be able to pay higher prices.

(vi) If the proportion of variable cost in the total cost is very high, there is no significant gap between marginal cost and full cost.

Method # 2. Market Oriented Pricing:

According to this approach, prices are to be changed in accordance with the changes in market conditions. When market conditions are very good then prices may be charged high and when market is sluggish then the prices may be lowered. It is a flexible approach where prices are set by demand. What is important is a price acceptable to the buyer. Sometimes it is referred to as what the traffic will bear method i.e. charging the maximum possible price given the market conditions.

Thus, the starting point of determining export prices is the price that the buyers are willing to pay for the product rather than the cost of production. The method of calculating market oriented pricing is that first of all “acceptable prices by the buyers” is estimated. Then the firm works backward to find its net prices by deducting from the market price the margins of various middlemen, internal taxes, import duties, export handling and freight charges, insurance and other export- related costs.

The resulting value gives the export base price. If this base price provides an acceptable return to the firms, the exports will be made and if not, the firms can decide not to export when it finds no scope of modifications, adjustments and readjustments in handling charges or commission to middlemen etc.

The major advantages of this method are:

(i) It is very flexible policy.

(ii) Price is based on the market conditions and from the view point of the customers.

(iii) When the product life, cycle is expected to be relatively short, ‘what the traffic will bear’ is an appropriate policy because it will enable the firm to recoup the investment fast.

(i) It is difficult to estimate what the traffic will bear.

(ii) In this method, there is a chance of ignoring the elasticity of demand factor.

(iii) If ‘what the traffic can bear’ may be different in different markets, it could lead to the development of a grey market.

(iv) It neglects the cost-pricing principles.

Method # 3. Price Leadership:

In price leadership the exporter follow the dominant competitors in setting the price. The price leader is the firm which indicates the price trends and other firms follow the leader.

The important alternatives open to the competitors are:

(a) Setting the price equal to that of the competitors.

(b) Setting the price higher than that of the competitors.

(c) Setting the price lower than that of the competitors.

The choice of the alternative is based on such factors as the comparative quality of the product, objective before the firms, the image and reputation of the firms, the uniqueness of any of the product, quicker supply of the product or any other the firm deems fit.

(i) It’s a simple method and follows the main market trend.

(ii) It avoids cut-throat competition.

(iii) It has relevance to the standing and reputation of the firm.

Demerits:

(i) The pricing objective of the exporter may be different from that of the competitors.

(ii) Sometimes the competitor may initiate price change for wrong reasons.

(iii) Sometimes the wrong and unrealistic decisions of the price leader may prove dangerous for the followers.

(iv) It neglects the cost variations among firms. All firms do not have the same cost structure.

Method # 4. Break-Even Price:

Break-even pricing is the price for a level of output at which there is neither any loss nor any profit i.e. Total Revenue (TR) is just equal to the Total Costs (TC) i.e. [TR = TC] Hence the terms break even. If the exporter sells below this price he suffers a loss and if he sells above this price, he earns the profit.

Break-even analysis helps to know the minimum sales required to avoid any loss. If the exporter sells more them the break-even quantity of output, he makes a profit and if the sale is less than the break-even volume, the result will be loss.

The Break-even point is expressed either as a percentage of capacity utilisation or in terms of physical units of output or in terms of total revenue from the sale of output etc.

The lower the break-even point, the higher is the chance of the project making profit and lower the risk of incurring losses. If the break-even point is high, the risk will also be very high.

Method # 5. Fixing the Price in Practice:

Deciding the price by negotiations between the exporter and the buyer is common in practice. This is popular with government and institutional purchases.

At the quoted price, negotiations between buyers and seller take place and the price is determined keeping in view their relative bargaining power, objective before the firm, demand pressures in the market, competitive rates prevailing, break-even price for the seller etc. Non-cost calculations, too, are taken into consideration while pricing for exports, example political overtones, market conditions abroad, export- subsidies to sellers etc.

The major advantage deciding price between the exporter and the buyer by negotiation is its greater flexibility and the opportunity to put across and understand the points of both buyers and exporters.

The major disadvantage is that if the bargaining power of the exporter is weak, he may not be able to get a good price.

Method # 6. Transfer Pricing:

Transfer pricing refers to the pricing between two firms which, though situated in two different countries are not independent of each other. This is applicable to multinational corporations (MNCs) when an MNC sells products or services across national boundaries to its subsidiary or affiliate, then the issue of transfer pricing or intra-firms pricing arises.

An MNC’s transfer pricing policy is basically influenced by various factors which are given below:

a. Nature of the subsidiaries.

b. Credit status of the parent company and the concerned subsidiary.

c. The prevailing competition and market conditions.

d. Laws on Income Tax in both the countries.

e. Their respective tariff rates.

f. Government regulations.

The objectives of transfer pricing are as follows:

a. Maximising overall after-tax profits.

b. Reducing incident of customs duty payments.

c. Circumventing the quota restrictions (in value terms) on imports.

d. Reducing exchange exposure, circumventing exchange controls and restricting profit repatriation so that transfer firms affiliates to the parent can be maximised.

e. Transferring of funds in locations so as to suit corporate working capital policies.

f. Window dressing’ operations to improve the apparent (i.e., reported) financial position of an affiliate so as to enhance its credit ratings.

g. Facilitating parent company control.

h. Offering management at all levels, both in the product divisions and in the international divisions, on adequate basis for maintaining, developing and receiving credit for their own profitability.

The objective of transfer price apparently seems simple allocation of profits among the subsidiaries and the parent company, but the differences in the taxation patterns in various markets makes it a complex phenomenon. Transfer prices come under the scrutiny of taxation authorities when it is different from the aim’s length price to unrelated parties.

Types of Transfer Pricing Methods:

Some important types of transfer pricing methods used in International Marketing are as follows:

1. Transfer at Cost:

Companies using the transfer-at-cost approach recognise that sales by international affiliates contribute to corporate profitability by generating scale economies in domestic manufacturing operations. This approach assumes lower costs lead to better affiliate performance, which ultimately benefits, the entire organisation. The transfer-at-cost method helps keep duties at a minimum. Companies using this approach have no profit expectation on transfer sales; rather, the expectation is that the affiliate will generate the profit by subsequent resale.

2. Cost-plus Pricing:

Companies that follow the cost-plus pricing method are taking the position that profit must be shown for any product or service at every stage of movement through the corporate system. While cost-plus pricing may result in a price that is completely unrelated to competitive or demand conditions in international markets, many exporters use this approach successfully.

3. Market-Based Transfer Price:

A market-based transfer price is derived from the price required to be competitive in the international market. The constraint on this price is cost. However, there is a considerable degree of variation in how costs are defined. Since costs generally decline with volume, a decision must be made regarding whether to price on the basis of current or planned volume levels. To use market-based transfer prices to enter a new market that is too small to support local manufacturing, third- country sourcing may be required. This enables a company to establish its name or franchise in the market without investing in bricks and mortar.

4. “Arm’s-Length” Transfer Pricing:

The price that would have been reached by unrelated parties in a similar transaction is referred to as “arm’s-length” transfer pricing. This approach requires identifying an arm’s-length price, which may be difficult to do except in the case of commodity-type products.

The arm’s-length price can be a useful target if it is viewed not as a single point but rather as a range of prices. The important thing to remember is that pricing at arm’s length in differentiated products results not in pre-determinable specific prices but in prices that fall within a pre-determinable range.

5. Tax Regulations and Transfer Prices:

Since the global corporation conducts business in a world characterised by different corporate tax rates, there is an incentive to maximise system income in countries with the lowest tax rates and to minimise income in high-tax countries. Governments, naturally, are well aware of this. In recent years, many governments have tried to maximise national tax revenues by examining company returns and mandating reallocation of income and expenses.

Pricing Methods in Marketing – 4 Major Methods

To set the specific price level that achieves their pricing objectives, managers may make use of several pricing methods.

These methods include:

a. Cost-plus pricing – Set the price at the production cost plus a certain profit margin.

b. Target return pricing – Set the price to achieve a target return-on-investment.

c. Value-based pricing – Base the price on the effective value to the customer relative to alternative products.

d. Psychological pricing – Base the price on factors such as signals of product quality, popular price points, and what the consumer perceives to be fair.

In addition to setting the price level, managers have the opportunity to design innovative pricing models that better meet the needs of both the firm and its customers. For example, software traditionally was purchased as a product in which customers made a one-time payment and then owned a perpetual license to the software.

Many software suppliers have changed their pricing to a subscription model in which the customer subscribes for a set period of time, such as one year. Afterwards, the subscription must be renewed or the software no longer will function. This model offers stability to both the supplier and the customer since it reduces the large swings in software investment cycles.

Pricing Methods in Marketing – Top 10 Methods

The pricing objectives provide guidelines for taking pricing decisions in the actual business world.

Different pricing methods are discussed below:

1. Full Cost or Cost-Plus Pricing:

Most people, when asked how prices are arrived at, will start from the cost of manufacture. The cost plus pricing or full cost pricing or mark-up pricing is widely prevalent in the business world. Many business firms believe that prices should bear equitable relation to costs. Full cost pricing means pricing at a level covering total costs and selling expenses plus a pre-determined mark-up.

A number of studies beginning with the well-known study by two Oxford economists, Hall and Hitch, have shown that business community set their prices by taking cost and adding a fair profit percentage. Sometimes a rigid, pre-determined mark-up is added to costs. Alternatively, the mark-ups are flexible, varying with business conditions. An example of a full-cost formula to determine price might be like this –

Cost of material and direct labour

+ percentage addition to cover overheads (say, 100%)

+ a percentage addition for selling expenses (say, 25%)

+ a fair margin for profit (say, 12%)

Generally many small firms apply full cost pricing in a mechanical way in the belief that costs are a solid basis on which to fix price. However, the definition of cost is beset with difficulties. Costs may mean actual cost or expected cost or standard cost.

2. Break-Even Pricing:

Another cost-oriented pricing approach is break-even pricing or a variation called target profit pricing. The break-even analysis is a device showing the relationship between sales value, variable and fixed cost and profit and loss at different levels of activity. The firm tries to determine the price at which it will break even or make the target profit it is seeking.

Break-even chart (Figure 23.1) shows the total cost and total revenue expected at different sales volume levels. The term break-even analysis is somewhat misleading in that the analysis is used to answer many other questions besides determining the break-even point—the volume at which net revenue is zero. In the Figure 23.1 total revenue function TR represents the total revenue that will be obtained if the firm charges a constant selling price per unit for the output.

Similarly, total cost function TC represents the total cost which will be incurred if cost consists of a fixed amount which is independent of the level of output and a constant variable cost per unit. Below an output level of Q, losses are incurred since TR < TC.

For output levels above Q, TR > TC and profits are earned. To determine the break-even point we have to plot the total revenue function. For a product with a constant selling price of Rs. P per unit the total revenue function is constructed by drawing a line through the origin with a slope of P. Next we have to plot the total cost function.

Given that the total cost consists of a fixed component (Rs. F) which is independent of the quantity of output produced and a variable component (Rs. V) which increases at a constant amount for each unit of output produced, then the total cost function is constructed by drawing a line that intersects the vertical cost axis and has the slope of V. Lastly we have to determine the point where total revenue and total cost lines intersect, and drop a perpendicular to the horizontal axis to get the value of Q.

The determination of the break-even point by algebraic methods consists of setting the total revenue and total cost functions equal to each other and solving the resulting equation for the break-even volume. Total revenue is equal to selling price per unit times the quantity sold –

TR = P x Q

And the total cost is equal to fixed cost plus variable cost, where variable cost is the product of the variable cost per unit and quantity produced –

The difference between the price per unit and the variable cost per unit (P – V) is sometimes referred to as the contribution margin per unit. It measures how much each unit of output contributes to meeting fixed costs and net profits. The break-even volume is equal to the fixed cost divided by the contribution margin per unit.

Illustration:

Let us illustrate these concepts with a concrete example. Construct a break-even chart with the following information –

In our figure, this is the volume where TC and TR intersect. In its crude form, the cost-plus pricing has the following limitations – (i) it ignores demand; (ii) it fails adequately to reflect the forces of competition; (iii) it exaggerates the precision of allocated costs; (iv) it may be based on a wrong perception of cost.

In spite of shortcomings, business firms adhere to full-cost pricing for the following reasons:

Firstly, it is said to be an ideal at which firms aim, rather than an attainable objective. Secondly, firms do not want to maximise profit. Price based on full costs are thought to be fair to consumers and competitors. Thirdly, price changes are costly and inconvenient to salesman. Fourthly, full cost is said to be the logical way to maximise long-run profit. Long-run prices tend to equal cost of production in the classical economic theory.

Fifthly, there is less uncertainty about costs than about demand. So by relying on costs, pricing is simplified and the seller need not make frequent adjustments as demand conditions change. It thus reduces the cost of decision making. Finally, it is argued that most alternative policies require that marginal cost should actually be identified and computed, which is practically very difficult.

3. Marginal Cost Pricing or Variable Cost Pricing:

In the cost-plus pricing and the rate of return pricing, prices are based on total costs—fixed as well as variable. Under marginal cost pricing, fixed costs are ignored and prices are determined on the basis of marginal cost. Instead of using full costs as the lowest possible price, this method suggests that variable cost represents the price that can be charged.

Since variable cost is the basis of pricing it is also known as variable cost pricing. In marginal cost pricing the objective of the firm is to maximise its total contribution to fixed costs and profit.

This system has several advantages. First, under marginal cost pricing, prices are never rendered uncompetitive because of higher fixed costs and orders will not be necessarily rejected because the prevailing price is below the average cost. Variable costs are controllable in short-run and hence prices based on variable costs will be flexible.

Secondly, marginal pricing helps a businessman to pursue a far more aggressive pricing policy than full-cost pricing. Such a price policy will increase the sale and possibly reduce marginal cost through increased physical productivity and lower input prices. Thirdly, marginal pricing is more helpful to fix price over the life cycle of the product, which requires short-run marginal cost and separate fixed cost data relevant to each stage of the cycle.

Fourthly, marginal cost pricing is more useful than full-cost pricing because of the prevalence of multi-product, multi-process and multi- market firms which makes the absorption of fixed costs into product costs difficult.

There are certain limitations of marginal cost pricing. First, it is argued that marginal pricing cannot be applied in practice because of administrative difficulties. Many businessmen are not familiar with marginal cost and marginal revenue. It is also difficult for businessmen to estimate future demand and costs accurately as a result of which there exists a discrepancy between planned and actual figures and profits are never maximised.

Secondly, the application of marginal pricing is that it leads to frequent price changes, which are not liked by the consumers. Buyers prefer stable prices and do not like rising prices in periods of temporary shortages.

Thirdly, during a period of business recession, firms using marginal pricing may cut prices in order to maintain business and this may induce other firms to reduce their prices also. This would lead to cut-throat competition. Lastly, it is also maintained that marginal pricing might lead to losses, as overheads are not covered by it.

There is general assumption that marginal costs are always below average costs, whereas they normally exceed the average costs. A rigid application of the full cost pricing may prove disastrous, for it is a mistake not to produce because the price does not cover full cost. Sometimes, it is wise to produce below average cost in order to increase total profit rather than stop production. Marginal cost pricing provides the upper and lower limits of pricing while full cost pricing clings only to the middle point.

4. Rate of Return Pricing:

Pricing to achieve a planned rate of return on investment is popular among a number of business firms. Here, the rate of return is taken as a given target. Whenever there is a change in the unit cost, the price is so adjusted that the target rate of return can be realised. The target rate of return may be set in three different ways. First, it may be set at the total profit as a percentage of total cost. Thus –

5. Going Rate Pricing:

Whereas in naive, full cost pricing the emphasis is on production, in going rate pricing it is on the market. In its simplest form, the going rate pricing prescription is simply to examine the general price structure in the industry, decide one’s own price accordingly going rate pricing is also known as imitative pricing.

This system of pricing is popular for the following reasons:

i. Where costs are difficult to measure this logical first step is a rational pricing policy.

ii. Going rate pricing is very popular in oligopolistic situations. It is followed to avoid a price war with the price leader. Many cases of going rate pricing are situations of price leadership. Where price leadership is well established, charging according to what competitors are charging may be the only safe policy. Going rate pricing may be a way in which firms try to avoid hazards of price war in an oligopolistic market.

iii. It may be less costly and troublesome to the business than the exact calculation of costs and demand and seems to have practical advantages over a highly individualistic pricing policy

Going rate pricing is not confined to small and medium-sized business. Some large American companies faced with what they regarded as a market-determined price, adopted a price set either by the market or by a price leader.

6. Product Tailoring:

Product tailoring refers to a policy of tailoring the cost of a product to a pre-determined price. It is an inverted cost-price relationship in which the price of the product appears to determine its cost instead of the other way round. In contrast to cost plus theory of pricing we have a price minus theory of cost.

Product tailoring is directly applicable only when the decision is fluid and when the target price is sharply defined by the economic situation with respect to substitutes and demand. This approach has the virtue of starting with market-price realities; it looks at the problem from the viewpoint of the buyer in terms of what he wants and what he will pay. This approach has a general applicability since the consumer is king and product design is generally subject to modification.

7. Refusal Pricing:

Refusal pricing refers to pricing products that are designed to the incremental cost plus a gross margin equivalent to the opportunity cost. Under this system, a floor price is set and the seller is engaged in refusal pricing for he has to decide whether or not to make the product at all; he is not deciding what to charge for the product that he has already decided to manufacture.

But even here, cost sets only a floor for prices, otherwise the seller might miss potential immediate profits and ignore the effects of price upon future business.

8. Product-Line Pricing:

Many companies, selling a wide range of products, gear their pricing strategy to the product-line as a whole rather than to individual products in the line. The problem of product-line pricing is to find the proper relationship among the prices of members of a product group.

Product-line pricing may refer to products that are physically distinct and also to products that are physically the same but sold under different demand conditions. The latter is known as differential pricing or prices discrimination. Price discrimination is thus a particular type of product-line pricing.

There are alternative methods of product-line pricing. In all these methods, prices are determined either by cost or elasticity of demand.

i. According to the first method prices are proportional to full cost and produce the same percentage net profit margin for all products. Under this scheme, each product assumes its full-allocated uniform percentage profit over this full cost. This pattern of product- line prices is produced by a strict adherence to cost-plus pricing.

Relative prices are then determined by the accounting conventions that govern the allocations of common costs among products. In practice these allocations are necessarily arbitrary from economic viewpoint. Moreover, this method gives no consideration to market factors.

ii. According to the second method, prices are proportional to incremental costs. This means that the prices produce the same percentage contribution margin over incremental costs for all products. The difference between the full-cost method and the incremental method is that while in the former method we take into account both average variable and fixed costs, in the latter method we consider only average variable costs.

This method is largely free from the defect of arbitrary allocation of common costs found in the first method since incremental costs usually require little arbitrary allocation of variable overheads. The defect of this method is that this price pattern does not take into account differences in demand and competitive conditions.

If members of product-line differ in superiority over competing products or are able to tap market sectors that can stand differential prices or different degrees of non-price competition, then a pattern of product-line prices that is proportional to incremental costs misses a significant profit opportunity. Incremental cost is a handy tool for product-line pricing; but its utility is destroyed if it becomes a basis for a mechanical cost-plus pricing formula.

iii. According to the third method, price with profit margins is proportional to conversion costs. Conversion costs are costs of converting raw materials into finished products and are equal to the sum of labour and overhead costs. This method of pricing has been advocated by WL Churchill on the grounds that conversion costs reflect the firm’s social contribution whereas purchased costs do not.

iv. According to the fourth method, prices should produce contribution margins that depend upon the elasticity of demand of different market segments. Buyers with high incomes are usually less sensitive to price than those that make up the mass market and it is often profitable to put higher profit margins on products for elite class markets than for mass markets.

v. According to the fifth method, prices should be systematically related to the stage of market and competitive development of individual members of the product line. Many products pass through life cycles. They start as novelties, then develop into distinctive specialties and ultimately degenerate into a common product. Different prices can be charged for the different stages of the life cycle of a product.

Two demand characteristics peculiar to multiple product-line are significant for pricing purpose. The first is the interdependence of the demand for various members of the product-line. Interdependence takes many forms. Products may by substitutes or complementary. The second demand characteristic in multiple- product lines is their importance as instruments for market segmentation and price discrimination.

They provide opportunities for breaking the market into smaller sectors that differ in price elasticity and hence can profitably charge different prices. Product design and pricing are major methods for achieving segmentation. Not only can market segmentation increase profits by setting prices that take advantage of the different elasticity of demand in each sector, it can also increase total sales by penetrating mass markets at prices that cover incremental costs and contribute a little to overheads.

Incremental cost concept is relevant for product-line pricing. Incremental concepts, comparing added revenue with added cost, can alone provide a criterion of whether or not an additional division of market is worthwhile. Incremental cost sets a lower limit for price in the most elastic sector of the market.

9. Cyclical Pricing:

Many pricing decisions of a firm relate to the fluctuations in business condition. Fluctuations in economic activity are known as business cycle. It has upswings and downswings. During the upswing, the demand for the firm’s products increases while during the downswing, the demand for the firm’s products declines. It is common knowledge that the prices of agricultural products and certain raw materials and manufactured goods have been predominantly flexible over the cycle.

But the prices of certain other raw materials and most manufactured products are generally inflexible. This is so because price leaders are reluctant to change their prices frequently and they often attempt to limit price cuts in periods of declining demand. They also refrain from major price increases in periods of rising demand.

There are four reasons for price inflexibility:

i. Demand:

It is a common belief among industrialists that demand for their products is highly inelastic and hence price changes will not lead to any appreciable change in demand. An increasing portion of nation’s output consists of durable goods. For such goods demand is more responsive to changes in consumer preference than to changes in the prices of the goods.

ii. Competition:

From the point of view of price competition, much of industrial pricing is done under oligopoly conditions and even the price leader has to maintain a degree of price stability in order to ward off retaliation from others. This in effect freezes prices and delays change, usually until other prices have started moving.

iii. Costs:

On the cost side, variable cost per unit tends to remain stable over long periods and over wide ranges of output on account of the rigidity of prices of raw materials and labour. Fixed costs per unit vary inversely with volume and with cyclically sensitive material prices. Current full costs, consequently, appear cyclically rigid and the prevalence of cost-plus pricing imparts some rigidity to prices.

iv. Profits:

On the side of profits, many firms, especially the price leaders who have considerable latitude in price making have generally as their goal a “reasonable” profit than profit maximisation. Hence, they may not lower or raise prices appreciably during the course of a business cycle.

The practical problems of cyclical pricing arise as to the degree, the timing and the pattern of cyclical price changes. A cyclical change in the level of net prices may take a variety of forms, viz., (a) changes in list prices, (b) changes in product-mix and product- line differentials, and (c) changes in the structure of discount and merchandising allowances.

In formulating policy on cyclical pricing, several possible policies are as follows:

i. Price rigidity

ii. Price fluctuations that conform to cost changes in –

a. Current full cost

b. Standard full cost

c. Incremental cost

iii. Price fluctuations that conform to prices of substitutes

iv. Price fluctuations that conform to changes in the general price level

v. Price fluctuations that stabilise market share

vi. Price fluctuations that conform to changes in industry demand determinants.

These policies might be characterised more accurately as objectives, since some of them cannot be fully attained.

i. Price Rigidity:

Absolute or approximate stability of the company’s price level over the course of the business cycle is a policy followed by some producers of industrial materials and equipment. It is largely based upon two assumptions – (a) the wide cyclical fluctuations in demand are caused by basic economic changes (e.g., in incomes, profits, expectations etc.) and (b) changes in the firm’s prices within the range of feasibility will be ineffective in altering these conditions or in tempering these cyclical fluctuations in demand.

ii. Price Fluctuations that Conform to Cost Changes:

Confining cyclical changes in price to changes in company costs is another popular cyclical price policy. This policy has several variants depending upon which concept of cost is employed, full cost, incremental cost or some form of standard cost. In essence, it amounts to stabilising some sort of unit profit margin.

iii. Price Fluctuations that Conform to Prices of Substitutes:

The use of substitute products as a cyclical pricing guide is an appropriate price policy in many situations. By keeping the spread between the firm’s product and substitute products stable or by manipulating it to obtain specified volume objectives, this cyclical pricing policy can protect or improve the company’s market position.

It may also stabilise the industry’s share of the vast substitute markets. In industries that have strong price leadership, the cyclical price policy employed by many price followers is of this type.

iv. Conformity to Changes in Purchasing Power:

Keeping the price in line with the falling purchasing power of money is a depression pricing standard that has strong appeal. But this kind of blanket index of purchasing power is an inferior pricing guide.

v. Price Fluctuations that Stabilise Market Share:

Price is an important background determinant of the market share particularly when products and services are dissimilar. Moreover, price policy has a profound effect upon the larger share of the substitute market. Market share can be useful pricing guide for cyclical pricing. The adoption of such a policy presupposes moderately accurate and current information about what is happening in market. It also requires alertness and flexibility in pricing.

vi. Price Fluctuations that Conform to Changes in Demand Determinants:

The demand schedules, both of the industry and of the firm, shift continuously as a result of the changes in general business conditions and changes in special outside conditions affecting that product. If these shifts in demand are pronounced, they should be taken into account in setting. In fact, they are often more important than the elasticity of demand.

To change prices in relationship to some appropriate index of shifts in demand for the product is a form of recession pricing policy. Sometimes it is possible to find a direct relationship between some index like disposable national income and the past fluctuations of the price of product. This functional relationship can then provide a rough criterion of the appropriate price at any given or forecasted level of demand.

The use of any such historical relationship as an absolute recession pricing criterion has severe limitations that destroy its usefulness in most industries. This pricing method implicitly assumes that (a) flexible, rather than rigid, prices are appropriate, (b) changes in the price in the past have adjusted for changes in demand correctly, (c) these past pricing objectives are today’s objectives, and (d) cost behaviour and competitive reactions will be the same as in similar periods in the past.

Pricing over the Life Cycle of a Product:

The innovation of a new product and its degeneration into a common product is termed as the life cycle of a product. A product has a life cycle comprising four stages of introduction, growth, maturity and decline.

The cycle begins with the innovation of a new product and it is often followed by patent protection. At the introductory stage the consumers do not know the product and hence the market is unexplored. This stage is followed by a rapid expansion in its sales as the product gains market acceptance.

Then competitors enter the market with rival products and the distinctiveness of the new product starts diminishing. The speed of degeneration differs from product to product. How long would be the overall life cycle and the duration of each phase would depend upon the type of the product and the degree of innovations affected in a given product line.

At the introductory stage the product is put on the market, hence awareness and acceptances are minimal. So here the emphasis should be on promotional activities so as to acquaint customers with the product and gain acceptance.

In the initial stage, with distinctive speciality a firm can charge a high price but as this characteristic fades away and the product becomes a pedestrian one, it has to either soften the pricing or bring out a change in the product to create some fresh interest so as to compete well with the new products brought out in the market.

The sales of product rises slowly and if the consumers accept it, there follows a period of rapid growth in sales volume. This stage is marked by increase in the number of competitors, major product improvements, penetration of other market segments etc. So, during this phase, emphasis must be given on opening new distribution channels and retail outlets.

When the product reaches maturity, sales growth continues, but at a diminishing rate, due to the declining number of potential customers. Special promotional efforts are needed to cope with such a situation.

Finally, the product reaches a stage of declining sales as it faces competition from better products or better substitutes developed by the competitors. At this stage the product has to be redesigned or the cost of production reduced so that they can continue to make same contribution to the company.

In the introductory stage, a firm with distinctive speciality can charge a high price but as this characteristic fades away the firm has to reduce prices. In a stage of maturity, price reduction alone may not pay off as other firms might do the same. Thus there is a need for continuous review of prices with reference to cost of production, product life cycle, elasticity of demand, selling costs etc. The four stages in the life cycle of a product is shown in Figure 23.2a.

10. Peak-Load Pricing:

Peak load pricing is used when there are definite limits to the amount of goods and services a firm can provide and customer demand tends to vary over time. This is a typical problem with service industries whose services cannot be stored, or storage of which is very expensive. During the peak period, demand is high and capacity is almost fully utilised while during the slack period, demand is low and considerable amount of capacity remains unutilised.

One example is telephone industry where consumption of service varies over the day but capacity must be able to meet the peak consumption of customers. During the peak periods that occur during the daytime, the telephone capacity is fully utilised while during nights there remain considerable amounts of unutilised capacity.

Peak-load pricing suggests that prices should be set at higher levels for the peak periods of demand while lower prices may be charged during the off-peak periods. The most important advantage of peak-load pricing is that it depresses peak demands and stimulates demand in the off-peak period. In this way it seeks to avoid excessive over-utilisation or excessive under-utilisation of capacity. This form of pricing is practised by the telephone and electricity industry.

The rate of telephone service is high during the peak period and low during the slack period. This tends to shift price-sensitive callers to low demand period and thus depress peak demands. Again, the low off-peak rates may help increase revenues by attracting some callers that normally do not use the phone for communication purpose. In this way the telephone industry may operate by avoiding both under-utilisation and over-utilisation of capacity.