Companies that make up a business combination frequently retain their legal identities as separate operating centers and maintain their own record-keeping. Thus, inventory sales between these companies trigger the independent accounting systems of both parties. The seller duly records revenue, and the buyer simultaneously enters the purchase into its accounts. For internal reporting purposes, recording an inventory transfer as a sale/purchase provides vital data to help measure the operational efficiency of each enterprise.

Despite the internal information benefits of accounting for the transaction in this manner, from a consolidated perspective neither a sale nor a purchase has occurred. An intercompany transfer is merely the internal movement of inventory, an event that creates no net change in the financial position of the business combination taken as a whole.

Thus, in producing consolidated financial statements, the recorded effects of these transfers are eliminated so that consolidated statements reflect only transactions with outside parties. Worksheet entries serve this purpose; they adapt the financial information reported by the separate companies to the perspective of the consolidated enterprise. The entire impact of the intercompany transactions must be identified and then removed. Deleting the actual transfer is described here first.

The Sales and Purchases Accounts:

To account for related companies as a single economic entity requires eliminating all intercompany sales/purchases balances. For example, if Arlington Company makes an $80,000 inventory sale to Zirkin Company, an affiliated party within a business combination, both parties record the transfer in their internal records as a normal sale/purchase.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The following consolidation worksheet entry is then necessary to remove the resulting balances from the externally reported figures:

Cost of Goods Sold is reduced here under the assumption that the Purchases account usually is closed out prior to the consolidation process.

In the preparation of consolidated financial statements, the preceding elimination must be made for all intercompany inventory transfers. The total recorded (intercompany) sales figure is deleted regardless of whether the transaction was downstream (from parent to subsidiary) or upstream (from subsidiary to parent). Furthermore, any markup included in the transfer price does not affect the elimination. Because the entire amount of the transfer occurred between related parties, the total effect must be removed in preparing the consolidated statements.

Unrealized Gross Profit—Year of Transfer (Year 1):

Removal of the sale/purchase is often just the first in a series of consolidation entries necessitated by inventory transfers. Despite the previous elimination, unrealized gross profits created by such sales can still exist in the accounting records at year-end. These profits initially result when the merchandise is priced at more than historical cost. Actual transfer prices are established in several ways, including the normal sales price of the inventory, sales price less a specified discount, or at a predetermined markup above cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Regardless of the method used for this pricing decision, intercompany profits that remain unrealized at year-end must be removed in arriving at consolidated figures.

All Inventory Remains at Year-End:

In the preceding illustration, assume that Arlington acquired or produced this inventory at a cost of $50,000 and then sold it to Zirkin, an affiliated party, at the indicated $80,000 price. From a consolidated perspective, the inventory still has a historical cost of only $50,000.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, Zirkin’s records now report it as an asset at the $80,000 transfer price. In addition, because of the markup, Arlington has recorded a $30,000 gross profit as a result of this intercompany sale. Because the transaction did not occur with an outside party, recognition of this profit is not appropriate for the combination as a whole.

Thus, although the consolidation entry TI shown earlier eliminated the sale/purchase figures, the $30,000 inflation created by the transfer price still exists in two areas of the individual statements:

i. Ending inventory remains overstated by $30,000.

ii. Gross profit is artificially overstated by this same amount.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Correcting the ending inventory requires only reducing the asset. However, before decreasing gross profit, the accounts affected by the incomplete earnings process should be identified. The ending inventory total serves as a negative component within the Cost of Goods Sold computation; it represents the portion of acquired inventory that was not sold.

Thus, the $30,000 overstatement of the inventory that is still held incorrectly decreases this expense (the inventory that was sold). Despite Entry TI, the inflated ending inventory figure causes cost of goods sold to be too low and, thus, profits to be too high by $30,000. For consolidation purposes, the expense is increased by this amount through a worksheet adjustment that properly removes the unrealized gross profit from consolidated net income.

Consequently, if all of the transferred inventory is retained by the business combination at the end of the year, the following worksheet entry also must be included to eliminate the effects of the seller’s gross profit that remains unrealized within the buyer’s ending inventory:

This entry (labeled G for gross profit) reduces the consolidated Inventory account to its original $50,000 historical cost. Furthermore, increasing Cost of Goods Sold by $30,000 effectively removes the unrealized amount from recognized gross profit. Thus, this worksheet entry resolves both reporting problems created by the transfer price markup.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Only a Portion of Inventory Remains:

Obviously, a company does not buy inventory to hold it for an indefinite time. It either uses the acquired items within the company’s operations or resells them to unrelated outside parties. Intercompany profits ultimately are realized by subsequently consuming or reselling these goods.

Therefore, only the transferred inventory still held at year-end continues to be recorded in the separate statements at a value more than the historical cost. For this reason, the elimination of unrealized gross profit (Entry G) is based not on total intercompany sales but only on the amount of transferred merchandise retained within the business at the end of the year.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To illustrate, assume that Arlington transferred inventory costing $50,000 to Zirkin, a related company, for $80,000, thus recording a gross profit of $30,000. Assume further that by year- end Zirkin has resold $60,000 of these goods to unrelated parties but retains the other $20,000 (for resale in the following year). From the viewpoint of the consolidated company, it has now earned the profit on the $60,000 portion of the intercompany sale and need not make an adjustment for consolidation purposes.

Conversely, any gross profit recorded in connection with the $20,000 in merchandise that remains is still a component within Zirkin’s Inventory account. Because the markup was 37½ percent ($30,000 gross profit/$80,000 transfer price), this retained inventory is stated at a value $7,500 more than its original cost ($20,000 × 37½%). The required reduction (Entry G) is not the entire $30,000 shown previously but only the $7,500 unrealized gross profit that remains in ending inventory.

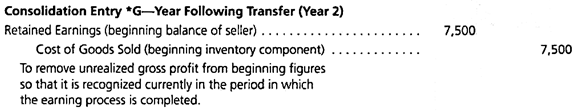

Unrealized Gross Profit—Year Following Transfer (Year 2):

Whenever an unrealized intercompany profit is present in ending inventory, one further consolidation entry is eventually required. Although Entry G removes the gross profit from the consolidated inventory balances in the year of transfer, the $7,500 overstatement remains within the separate financial records of the buyer and seller. The effects of this deferred gross profit are carried into their beginning balances in the subsequent year.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Hence, a worksheet adjustment is necessary in the period following the transfer. For consolidation purposes, the unrealized portion of the intercompany gross profit must be adjusted in two successive years (from ending inventory in the year of transfer and from beginning inventory of the next period).

Referring again to Arlington’s sale of inventory to Zirkin, the $7,500 unrealized gross profit is still in Zirkin’s Inventory account at the start of the subsequent year. Once again, the overstatement is removed within the consolidation process but this time from the beginning inventory balance (which appears in the financial statements only as a positive component of cost of goods sold). This elimination is termed Entry *G. The asterisk indicates that a previous year transfer created the intercompany gross profits.

Reducing Cost of Goods Sold (beginning inventory) through this worksheet entry increases the gross profit reported for this second year. For consolidation purposes, the gross profit on the transfer is recognized in the period in which the items are actually sold to outside parties.

As shown in the following diagram, Entry G initially deferred the $7,500 gross profit because this amount was unrealized in the year of transfer. Entry *G now increases consolidated net income (by decreasing cost of goods sold) to reflect the earning process in the current year.

In Entry *G, removal of the $7,500 from beginning inventory (within Cost of Goods Sold) appropriately increases current income and should not pose a significant conceptual problem. However, the rationale for decreasing the seller’s beginning Retained Earnings deserves further explanation. This reduction removes the unrealized gross profit (recognized by the seller in the year of transfer) so that the profit is reported in the period when it is earned.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Despite the consolidation entries in Year 1, the $7,500 gain remained on this company’s separate books and was closed to Retained Earnings at the end of the period. Recall that consolidation entries are never posted to the individual affiliate’s books. Therefore, from a consolidated view, the buyer’s Inventory and the seller’s Retained Earnings accounts as of the beginning of Year 2 contain the unrealized profit, and must both be reduced in Entry *G.

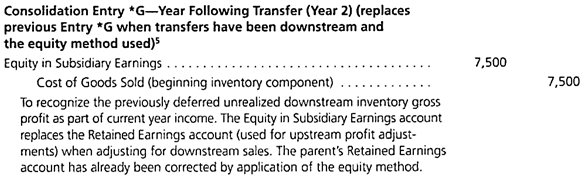

Intercompany Beginning Inventory Profit Adjustment—Downstream Sales When Parent uses Equity Method:

The worksheet elimination of the sales/purchases balances (Entry TI) and the entry to remove the unrealized gross profit from ending Inventory in Year 1 (Entry G) are both standard, regardless of the circumstances of the consolidation. Conversely, in one specific situation, the procedure used to eliminate the intercompany gross profit from Year 2’s beginning account balances differs from the Entry *G just presented. If (1) the original transfer is downstream (made by the parent) and (2) the equity method has been applied for internal accounting purposes, the Equity in Subsidiary Earnings account replaces beginning Retained Earnings in Entry *G.

When using the equity method the parent maintains appropriate income balances within its own individual financial records. Thus, the parent defers any unrealized gross profit at the end of Year 1 through an equity method adjustment that also decreases the Investment in Subsidiary account. With the profit deferred, the Retained Earnings of the parent/seller at the beginning of the following year is correctly stated. The parent’s Retained Earnings does not contain the unrealized gross profit and needs no adjustment.

At the end of Year 2, both the Equity in Subsidiary Earnings and the Investment accounts are increased in recognition of the previously deferred intercompany profit. The Investment account— having been decreased in Year 1 and increased in Year 2 for the intercompany gross profit—thus no longer reflects any effects from the original deferral. For consolidation purposes, Entry *G simply transfers the income effect of the realized gross profit from the Equity in Subsidiary Earnings account to Cost of Goods Sold appropriately increasing current consolidated income.

The remaining balance in the Equity in Subsidiary Earnings account now reflects the same activity represented in the Investment account and is subsequently eliminated against the Investment account.

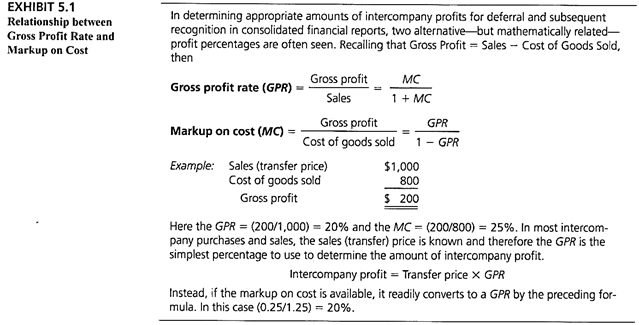

Finally, various markup percentages determine the dollar values for intercompany profit deferrals. Exhibit 5.1 shows formulas for both the gross profit rate and markup on cost and the relation between the two.

Unrealized Gross Profits—Effect on Non-Controlling Interest Valuation:

The worksheet entries just described appropriately account for the effects of intercompany inventory transfers on business combinations. However, one question remains. What impact do these procedures have on the valuation of a non-controlling interest?

The last sentence indicates that alternative approaches are available in computing the non- controlling interest’s share of a subsidiary’s net income. According to this pronouncement, unrealized gross profits resulting from intercompany transfers may or may not affect recognition of outside ownership. Because the amount attributed to a non-controlling interest reduces consolidated net income, the handling of this issue can affect the reported profitability of a business combination.

To illustrate, assume that Large Company owns 70 percent of the voting stock of Small Company. To avoid extraneous complications, assume that no amortization expense resulted from this acquisition. Assume further that Large reports current net income (from separate operations) of $500,000 while Small earns $100,000. During the current period intercompany transfers of $200,000 occur with a total markup of $90,000. At the end of the year, an unrealized intercompany gross profit of $40,000 remains within the inventory accounts.

Clearly, the consolidated net income prior to the reduction for the 30 percent non-controlling interest is $560,000, the two income balances less the unrealized gross profit. The problem facing the accountant is the computation of the non-controlling interest’s share of Small’s income.

Because of the flexibility allowed by SFAS 160, this figure may be reported as either $30,000 (30 percent of the $100,000 earnings of the subsidiary) or $18,000 (30 percent of reported income after that figure is reduced by the $40,000 unrealized gross profit).

To determine an appropriate valuation for this noncontrolling interest allocation, the relationship between an intercompany transaction and the outside owners must be analyzed. If a transfer is downstream (the parent sells inventory to the subsidiary), a logical view would seem to be that the unrealized gross profit is that of the parent company. The parent made the original sale; therefore, the gross profit is included in its financial records.

Because the subsidiary’s income is unaffected little justification exists for adjusting the noncontrolling interest to reflect the deferral of the unrealized gross profit. Consequently, in the example of Large and Small, if the transfers were downstream, the 30 percent noncontrolling interest would be $30,000 based on Small’s reported income of $100,000.

In contrast, if the subsidiary sells inventory to the parent (an upstream transfer), the subsidiary’s financial records would recognize the gross profit even though part of this income remains unrealized from a consolidation perspective. Because the outside owners possess their interest in the subsidiary, a reasonable conclusion would be that valuation of the noncontrolling interest is calculated on the income this company actually earned.

The noncontrolling interest’s share of consolidated net income is computed based on the reported income of the subsidiary after adjustment for any unrealized upstream gross profits. Returning to Large Company and Small Company, if the $40,000 unrealized gross profit results from an upstream sale from subsidiary to parent, only $60,000 of Small’s $100,000 reported income actually has been earned by the end of the year. The allocation to the noncontrolling interest is, therefore, reported as $18,000, or 30 percent of this realized income figure.

Although the noncontrolling interest figure is based here on the subsidiary’s reported income adjusted for the effects of upstream intercompany transfers, SFAS 160, as quoted earlier, does not require this treatment. Giving effect to upstream transfers in this calculation but not to downstream transfers is no more than an attempt to select the most logical approach from among acceptable alternatives.

Intercompany Inventory Transfers Summarized:

To assist in overcoming the complications created by intercompany transfers, we demonstrate the consolidation process in three different ways:

i. Before proceeding to a numerical example, review the impact of intercompany transfers on consolidated figures. Ultimately, the accountant must understand how the balances reported by a business combination are derived when unrealized gross profits result from either upstream or downstream sales.

ii. Next, two different consolidation worksheets are produced: one for downstream transfers and the other for upstream. The various consolidation procedures used in these worksheets are explained and analyzed.

iii. Finally, several of the consolidation worksheet entries are shown side by side to illustrate the differences created by the direction of the transfers.

The Development of Consolidated Totals:

The following summary discusses the accounts affected by intercompany inventory transactions:

Revenues:

The parent’s balance is added to the subsidiary’s balance, but all intercompany transfers are then removed.

Cost of Goods Sold:

The parent’s balance is added to the subsidiary’s balance, but all intercompany transfers are removed. The resulting total is decreased by any beginning unrealized gross profit (thus raising net income) and increased by any ending unrealized gross profit (reducing net income).

Expenses:

The parent’s balance is added to the subsidiary’s balance plus any amortization expense for the year recognized on the purchase price allocations.

Noncontrolling Interest in Subsidiary’s Net Income:

The subsidiary’s reported net income is adjusted for any excess acquisition-date fair-value amortizations and the effects of unrealized gross profits on upstream transfers (but not downstream transfers) and then multiplied by the percentage of outside ownership.

Retained Earnings at the Beginning of the Year:

If the equity method is applied the parent’s balance mirrors the consolidated total. When any other method is used the parent’s beginning Retained Earnings must be converted to the equity method by Entry *C. Accruals for this purpose are based on the income actually earned by the subsidiary in previous years (reported income adjusted for any unrealized upstream gross profits).

Inventory:

The parent’s balance is added to the subsidiary’s balance. Any unrealized gross profit remaining at the end of the current year is removed to adjust the reported balance to historical cost.

Land, Buildings, and Equipment:

The parent’s balance is added to the subsidiary’s balance. This total is adjusted for any excess fair-value allocations and subsequent amortization.

Non-Controlling Interest in Subsidiary at End of Year:

The final total begins with the noncontrolling interest at the beginning of the year. This figure is based on the subsidiary’s book value on that date plus its share of any unamortized acquisition-date excess fair value less any unrealized gross profits on upstream sales. The beginning balance is updated by adding the portion of the subsidiary’s income assigned to these outside owners and subtracting the noncontrolling interest’s share of the subsidiary’s dividend payments.

Intercompany Inventory Transfers Illustrated:

To examine the various consolidation procedures required by intercompany inventory transfers, assume that Top Company acquires 80 percent of the voting stock of Bottom Company on January 1, 2009. The parent pays $400,000 and the acquisition-date fair value of the non- controlling interest is $100,000. Top allocates the entire $50,000 excess fair value over book value to adjust a database owned by Bottom to fair value. The database has an estimated remaining life of 20 years.

The subsidiary reports net income of $30,000 in 2009 and $70,000 in 2010, the current year. Dividend payments are $20,000 in the first year and $50,000 in the second. Top applies the initial value method so that the parent records dividend income of $16,000 ($20,000 × 80%) and $40,000 ($50,000 × 80%) during these two years. Using the initial value method in this next example avoids the problem of computing the parent’s investment account balances. However, this illustration is subsequently extended to demonstrate the changes necessary when the parent applies the equity method.

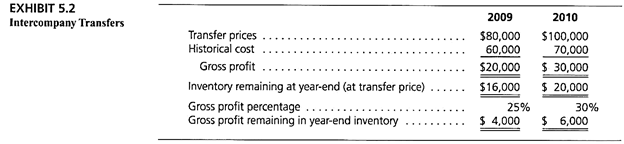

After the takeover, intercompany inventory transfers between the two companies occurred as shown in Exhibit 5.2. A $10,000 intercompany debt also exists as of December 31, 2010.

The 2010 consolidation of Top and Bottom is presented twice. First, the transfers are assumed to be downstream from parent to subsidiary (Exhibit 5.3).

Second consolidated figures are recomputed with the transfers being viewed as upstream (Exhibit 5.4). This distinction is significant only because of a noncontrolling interest.

Downstream Sales:

In the first example, all inventory transfers are assumed to be downstream from Top to Bottom. Based on that perspective, the worksheet to consolidate these two companies for the year ending December 31, 2010, is in Exhibit 5.3.

Thus, only four of these entries are examined in detail along with the computation of the noncontrolling interests in the subsidiary’s income.

Entry *G:

Entry *G removes the unrealized gross profits carried over from the previous period. The gross profit on the $16,000 in transferred merchandise held by Bottom at the beginning of the current year was unearned and deferred in the 2009 consolidated statements.

The 2009 gross profit rate (Exhibit 5.2) on these items was 25 percent ($20,000 gross profit/$80,000 transfer price), indicating an unrealized profit of $4,000 (25 percent of the remaining $16,000 in inventory). To recognize this gross profit in 2010, Entry *G reduces cost of goods sold (or the beginning inventory component of that expense) by that amount and Top’s (as the seller of the goods) January 1, 2010, Retained Earnings. Essentially the $4,000 gross profit is removed from 2009 retained earnings and recognized in 2010 consolidated net income.

Entry *G creates two effects- First, last year’s profits, as reflected in the seller’s beginning Retained Earnings, are reduced because the $4,000 gross profit was not earned at that time. Second the reduction in Cost of Goods Sold creates an increase in current year income. From a consolidation perspective, the gross profit is correctly recognized in 2010 when the inventory is sold to an outside party.

Entry *C:

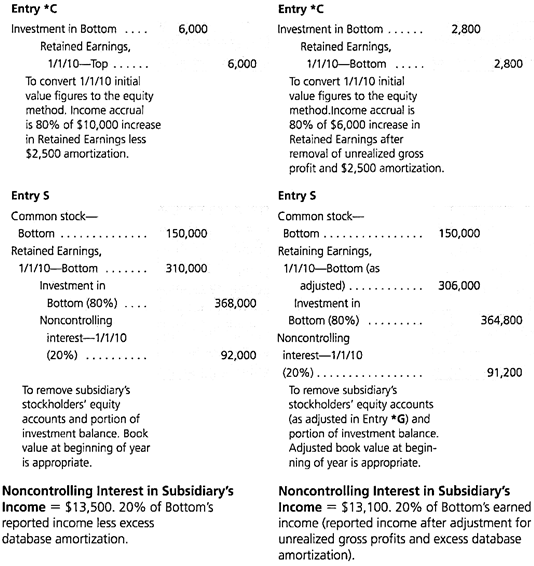

Entry *C as an initial consolidation adjustment required whenever the parent does not apply the equity method. Entry *C converts the parent’s beginning Retained Earnings to a consolidated total. In the current illustration, Top did not accrue its portion of the 2009 increase in Bottom’s book value [($30,000 income less $20,000 paid in dividends) × 80%, or $8,000] or record the $2,000 amortization expense for this same period.

Because the parent recognized neither number in its financial records, the consolidation process adjusts the parent’s beginning retained earnings by $6,000 (Entry *C). The intercompany transfers do not affect this entry because they were downstream; the gross profits had no impact on the income the subsidiary recognized.

Entry TI:

Entry TI eliminates the intercompany sales/purchases for 2010. The entire $100,000 transfer recorded by the two parties during the current period is removed to arrive at consolidated figures for the business combination.

Entry G:

Entry G defers the unrealized gross profit remaining at the end of 2010. The $20,000 in transferred merchandise (Exhibit 5.2) that Bottom has not yet sold has a markup of 30 percent ($30,000 gross profit/$ 100,000 transfer price); thus, the unrealized gross profit amounts to $6,000. On the worksheet, Entry G eliminates this overstatement in the Inventory asset balance as well as the ending inventory (negative) component of Cost of Goods Sold. Because the gross profit remains unrealized the increase in this expense appropriately decreases consolidated income.

Noncontrolling Interest’s Share of the Subsidiary’s Income:

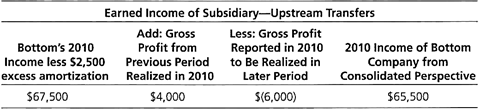

In this first illustration, the intercompany transfers are downstream. Thus, the unrealized gross profits are considered to relate solely to the parent company, creating no effect on the subsidiary or the outside ownership. For this reason, the noncontrolling interest’s share of the subsidiary’s income is unaffected by the downstream intercompany profit deferral and subsequent recognition. Therefore, Top allocates $13,500 of Bottom’s income to the noncontrolling interest computed as 20 percent of $67,500 ($70,000 reported income less $2,500 current year database excess fair- value amortization).

By including these entries along with the other routine worksheet eliminations and adjustments, the accounting information generated by Top and Bottom is brought together into a single set of consolidated financial statements. However, this process does more than simply delete intercompany transactions; it also affects reported income. A $4,000 gross profit is removed on the worksheet from 2009 figures and subsequently recognized in 2010 (Entry *G). A $6,000 gross profit is deferred in a similar fashion from 2010 (Entry G) and subsequently recognized in 2011. However, these changes do not affect the noncontrolling interest because the transfers were downstream.

A different set of consolidation procedures is necessary if the intercompany transfers are upstream from Bottom to Top. As previously discussed upstream gross profits are attributed to the subsidiary rather than to the parent company. Therefore, had these transfers been upstream, the $4,000 gross profit moved from 2009 into the current year (Entry *G) and the $6,000 unrealized gross profit deferred from 2010 into the future (Entry G) are both considered adjustments to Bottom’s reported totals.

Tying upstream gross profits to Bottom’s income complicates the consolidation process in several ways:

i. Deferring the $4,000 gross profit from 2009 into 2010 dictates the adjustment of the subsidiary’s beginning Retained Earnings balance (as the seller of the goods) to $306,000 rather than $310,000 found in the company’s separate records on the worksheet.

ii. Because $4,000 of the income reported for 2009 was unearned at that time, Bottom’s book value did not increase by $10,000 during the previous period (income less dividends as stated in the introduction) but only by an earned amount of $6,000.

iii. Bottom’s earned income for the year 2010 is $65,500 rather than the $70,000 found within the company’s separate financial statements. This $65,500 figure is based on adjusting the timing of the reported income to reflect the deferral and recognition of the intercompany gross profits and excess fair-value amortization.

Determinations of Bottom’s beginning Retained Earnings (realized) to be $306,000 and its 2010 income as $65,500 are preliminary calculations made in anticipation of the consolidation process. These newly computed totals are significant because they serve as the basis for several worksheet entries. However, the subsidiary’s financial records remain unaffected. In addition, because the initial value method has been applied no change is required in any of the parent’s accounts on the worksheet.

To illustrate the effects of upstream inventory transfers, in Exhibit 5.4, we consolidate the financial statements of Top and Bottom again. The individual records of the two companies are unchanged from Exhibit 5.3: The only difference in this second worksheet is that the intercompany transfers are assumed to have been made upstream from Bottom to Top. This single change creates several important differences between Exhibits 5.3 and 5.4.

1. Because the intercompany sales are made upstream, the $4,000 deferral of the beginning unrealized gross profit (Entry *G) is no longer a reduction in the parent company’s retained earnings, if Bottom sold the merchandise; thus, the elimination made in Exhibit 5.4 reduces that company’s January 1, 2010, equity balance. Following this entry, Bottom’s beginning Retained Earnings on the worksheet is $306,000, which is, as discussed earlier, and the appropriate total from a consolidated perspective.

2. Because $4,000 of Bottom’s 2009 income is deferred until 2010, the increase in the subsidiary’s book value in the previous year is only $6,000 rather than $10,000 as reported.

Consequently, conversion to the equity method (Entry *C) requires an increase of just $2,800:

3. Within Entry S, the valuation of the initial noncontrolling interest and the portion of the parent’s investment account to be eliminated differ from the previous example. This worksheet entry removes the stockholders’ equity accounts of the subsidiary as of the beginning of the current year. Thus, the $4,000 reduction made to Bottom’s Retained Earnings to remove the 2009 unrealized gross profit must be considered in developing Entry S.

After posting Entry *G, only $456,000 remains as the subsidiary’s January 1, 2010, book value (the total of Common Stock and beginning Retained Earnings accounts after adjustment for (Entry *G). This figure forms the basis for the 20 percent noncontrolling interest ($91,200) and the elimination of the 80 percent parent company investment ($364,800).

4. Finally, to complete the consolidation, the noncontrolling interest’s share of the subsidiary’s net income is recorded on the worksheet as $13,100 computed as follows:

Upstream transfers affect this computation although the downstream sales in the previous example did not. Thus, the noncontrolling interest balance reported previously in the income statement in Exhibit 5.3 differs from the allocation in Exhibit 5.4.

Consolidations—Downstream versus Upstream Transfers:

To help clarify the effect of downstream and upstream transfers, the worksheet entries that differ can be examined in more detail.

Effects of Alternative Investment Methods on Consolidation:

Exhibits 5.3 and 5.4 utilized the initial value method. However, when using either the equity method or the partial equity method consolidation procedures normally continue to follow the same patterns. Though, a variation in Entry *G is required when the equity method is applied and downstream transfers have occurred. The equity in subsidiary earnings account is decreased rather than recording a reduction in the beginning retained earnings of the parent/seller with the remaining amount in equity in subsidiary earnings eliminated in Entry I. Otherwise, the specific accounting method in use creates no unique impact on the consolidation process for intercompany transactions.

The major complication when the parent uses the equity method is not always related to a consolidation procedure. Frequently, the composition of the investment-related balances appearing on the parent’s separate financial records proves to be the most complex element of the entire process. Under the equity method the investment-related accounts are subjected to- (1) income accrual, (2) amortization, (3) dividends, and (4) adjustments required by unrealized intercompany gains.

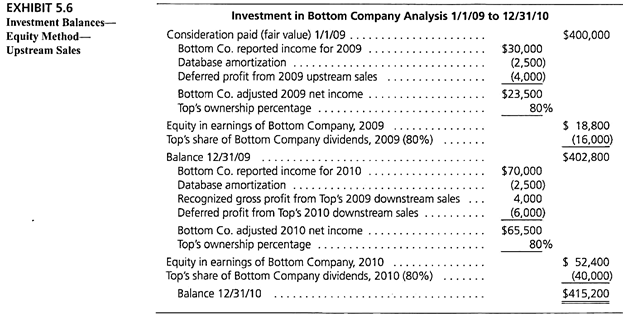

Thus, if Top Company applies the equity method and the transfers are downstream, the Investment in Bottom Company account increases from $400,000 to $414,000 by the end of 2010. For that year, the Equity in Earnings of Bottom Company account registers a $52,000 balance. Both of these totals result from the accounting shown in Exhibit 5.5.

If transfers are upstream, the individual investment-related accounts that the parent reports can be determined in the same manner as in Exhibit 5.5. Because of the change in direction, the gross profits are now attributed to the subsidiary. Thus, both accounts related to the investment in Bottom hold balances that vary from the totals computed earlier.

The Investment in Bottom Company balance becomes $415,200, whereas the Equity in Earnings of Bottom Company account for the year is $52,400. The differences result from having upstream rather than downstream transfers. The components of these accounts are identified in Exhibit 5.6.

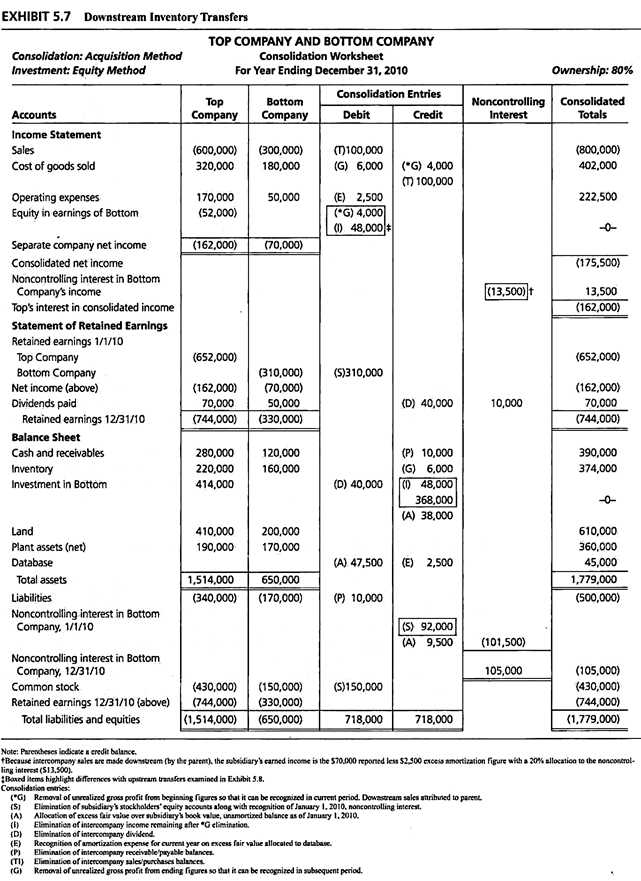

Consolidated worksheets for downstream and upstream inventory transfers when Top uses the equity method are shown in Exhibit 5.7 and Exhibit 5.8.

Special Equity Method Procedures for Unrealized Intercompany Profits from Downstream Transfers:

Exhibit 5.5 shows an analysis of the parent’s equity method investment accounting procedures in the presence of unrealized intercompany gross profits resulting from downstream inventory transfers. This application of the equity method differs for a significant influence (typically 20 to 50 percent ownership) investment.

For significant influence investments, an investor company defers unrealized intercompany gross profits only to the extent of its percentage ownership, regardless of whether the profits resulted from upstream or downstream transfers. In contrast, Exhibit 5.5 shows a 100 percent deferral in 2009, with a subsequent 100 percent recognition in 2010, for intercompany gross profits resulting from Top’s inventory transfers to Bottom, its 80 percent owned subsidiary.

Why the distinction? Because when control (rather than just significant influence) exists, 100 percent of all intercompany gross profits are eventually removed from consolidated net income regardless of the direction of the underlying sale. The 100 percent intercompany profit deferral on Top’s books for downstream sales explicitly recognizes that none of the deferral will be allocated to the non-controlling interest.

When the parent is the seller in an intercompany transfer, little justification exists for it to allocate a portion of the gross profit deferral to the noncontrolling interest. In contrast, for an upstream sale, the subsidiary recognizes the gross profit on its books. Because the noncontrolling interest owns a portion of the subsidiary (but not of the parent), allocation of intercompany gross profit deferrals and subsequent recognitions across the non-controlling interest and the parent appear appropriate.