Just as related parties can transfer land the intercompany sale of a host of other assets is possible. Equipment, patents, franchises, buildings, and other long-lived assets can be involved. Accounting for these transactions resembles that demonstrated for land sales. However, the subsequent calculation of depreciation or amortization provides an added challenge in the development of consolidated statements.

Deferral of Unrealized Gains:

When faced with intercompany sales of depreciable assets, the accountant’s basic objective remains unchanged: to defer unrealized gains to establish both historical cost balances and recognize appropriate income within the consolidated statements. More specifically, accountants defer gains created by these transfers until such time as the subsequent use or resale of the asset consummates the original transaction. For inventory sales, the culminating disposal normally occurs currently or in the year following the transfer. In contrast, transferred land is quite often never resold thus permanently deferring the recognition of the intercompany profit.

For depreciable asset transfers, the ultimate realization of the gain normally occurs in a different manner; the property’s use within the buyer’s operations is reflected through depreciation. Recognition of this expense reduces the asset’s book value every year and hence, the overvaluation within that balance.

The depreciation systematically eliminates the unrealized gain not only from the asset account but also from Retained Earnings. For the buyer, excess expense results each year because the computation is based on the inflated transfer cost. This depreciation is then closed annually into Retained Earnings. From a consolidated perspective, the extra expense gradually offsets the unrealized gain within this equity account. In fact, over the life of the asset, the depreciation process eliminates all effects of the transfer from both the asset balance and the Retained Earnings account.

Depreciable Asset Transfers Illustrated:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To examine the consolidation procedures required by the intercompany transfer of a depreciable asset, assume that Able Company sells equipment to Baker Company at the current market value of $90,000. Able originally acquired the equipment for $100,000 several years ago; since that time, it has recorded $40,000 in accumulated depreciation. The transfer is made on January 1, 2009, when the equipment has a 10-year remaining life.

The 2009 effects on the separate financial accounts of the two companies can be quickly enumerated:

1. Baker, as the buyer, enters the equipment into its records at the $90,000 transfer price. However, from a consolidated view, the $60,000 book value ($100,000 cost less $40,000 accumulated depreciation) is still appropriate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Able, as the seller, reports a $30,000 profit, although the combination has not yet earned anything. Able then closes this gain into its Retained Earnings account at the end of 2009.

3. Assuming application of the straight-line depreciation method with no salvage value, Baker records expense of $9,000 at the end of 2009 ($90,000 transfer price/10 years). The buyer recognizes this amount rather than the $6,000 depreciation figure applicable to the consolidated entity ($60,000 book value/10 years).

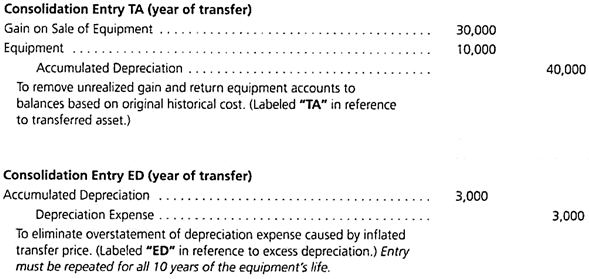

To report these events as seen by the business combination, both the $30,000 unrealized gain and the $3,000 overstatement in depreciation expense must be eliminated on the worksheet. For clarification purposes, two separate consolidation entries for 2009 follow.

However, they can be combined into a single adjustment:

From the viewpoint of a single entity, these entries accomplish several objectives:

i. Reinstate the asset’s historical cost of $100,000.

ii. Return the January 1, 2009, book value to the appropriate $60,000 figure by recognizing accumulated depreciation of $40,000.

iii. Eliminate the $30,000 unrealized gain recorded by Able so that this intercompany profit does not appear in the consolidated income statement.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

iv. Reduce depreciation for the year from $9,000 to $6,000, the appropriate expense based on historical cost.

In the year of the intercompany depreciable asset transfer, the preceding consolidation entries TA and ED are applicable regardless of whether the transfer was upstream or downstream. They are likewise applicable regardless of whether the parent applies the equity method initial value method or partial equity method of accounting for its investment. As discussed subsequently, however, in the years following the intercompany transfer, a slight modification must be made to the consolidation entry *TA when the equity method is applied and the transfer is downstream.

Again, the preceding worksheet entries do not actually remove the effects of the intercompany transfer from the individual records of these two organizations. Both the unrealized gain and the excess depreciation expense remain on the separate books and are closed into Retained Earnings of the respective companies at year-end.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Similarly, the Equipment account with the related accumulated depreciation continues to hold balances based on the transfer price, not historical cost. Thus, for every subsequent period, the separately reported figures must be adjusted on the worksheet to present the consolidated totals from a single entity’s perspective.

To derive worksheet entries at any future point, the balances in the accounts of the individual companies must be ascertained and compared to the figures appropriate for the business combination. As an illustration, the separate records of Able and Baker two years after the transfer (December 31, 2010) follow. Consolidated totals are calculated based on the original historical cost of $100,000 and accumulated depreciation of $40,000.

Because the transfer’s effects continue to exist in the separate financial records, the various accounts must be corrected in each succeeding consolidation. However, the amounts involved must be updated every period because of the continual impact that depreciation has on these balances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

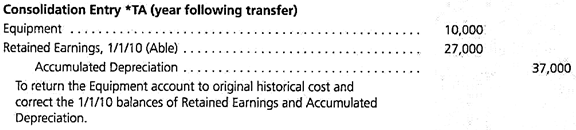

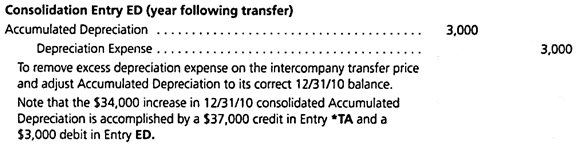

As an example, to adjust the individual figures to the consolidated totals derived earlier, the 2010 worksheet must include the following entries:

Although adjustments of the asset and depreciation expense remain constant, the change in beginning Retained Earnings and Accumulated Depreciation varies with each succeeding consolidation. At December 31, 2009, the individual companies closed out both the unrealized gain of $30,000 and the initial $3,000 overstatement of depreciation expense. Therefore, as reflected in Entry *TA, the beginning Retained Earnings account for 2010 is overvalued by a net amount of only $27,000 rather than $30,000.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Over the life of the asset, the unrealized gain in retained earnings will be systematically reduced to zero as excess depreciation expense ($3,000) is closed out each year. Hence, on subsequent consolidation worksheets, the beginning Retained Earnings account decreases by this amount $27,000 in 2010, $24,000 in 2011, and $21,000 in the following period. This reduction continues until the effect of the unrealized gain no longer exists at the end of 10 years.

If this equipment is ever resold to an outside party, the remaining portion of the gain is considered earned. As in the previous discussion of land, the intercompany profit that exists at that date must be recognized on the consolidated income statement to arrive at the appropriate amount of gain or loss on the sale.

Depreciable Intercompany Asset Transfers—Downstream Transfers when the Parent uses the Equity Method:

A slight modification to consolidation entry *TA is required when the intercompany depreciable asset transfer is downstream and the parent uses the equity method. In applying the equity method, the parent adjusts its book income for both the original transfer gain and periodic depreciation expense adjustments. Thus, in downstream intercompany transfers when the equity method is used, from a consolidated view, the book value of the parent’s Retained Earnings balance has been already reduced for the gain.

Therefore, continuing with the previous example, the following worksheet consolidation entries would be made for a downstream sale assuming that- (1) Able is the parent and (2) Able has applied the equity method to account for its investment in Baker.

In Entry *TA, note that the Investment in Baker account replaces the parent’s Retained Earnings. The debit to the investment account effectively allocates the write-down necessitated by the intercompany transfer to the appropriate subsidiary equipment and accumulated depreciation accounts.

Effect on Non-Controlling Interest Valuation— Depreciable Asset Transfers:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Because of the lack of official guidance, no easy answer exists as to the assignment of any income effects created within the consolidation process. All income is assigned here to the original seller. In Entry *TA, for example, the beginning Retained Earnings account of Able (the seller) is reduced. Both the unrealized gain on the transfer and the excess depreciation expense subsequently recognized are assigned to that party.

Thus, again, downstream sales are assumed to have no effect on any non-controlling interest values. The parent rather than the subsidiary made the sale. Conversely, the impact on income created by upstream sales must be considered in computing the balances attributed to these outside owners. Currently, this approach is one of many acceptable alternatives. However, in its future deliberations on consolidation .policies and procedures, the FASB could mandate a specific allocation pattern.