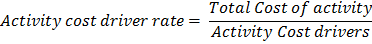

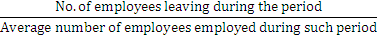

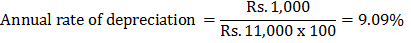

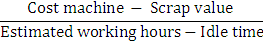

In this article we will discuss about:- 1. The Reporting of Investments in Corporate Equity Securities 2. Accounting for an Investment—the Equity Method 3. Accounting Procedures Used in Applying the Equity Method 4. Excess of Investment Cost Over Book Value Acquired 5. Elimination of Unrealized Profits in Inventory 6. Fair-Value Reporting Option for Equity Method Investments.

Contents:

- The Reporting of Investments in Corporate Equity Securities

- Accounting for an Investment—the Equity Method

- Accounting Procedures Used in Applying the Equity Method

- Excess of Investment Cost Over Book Value Acquired

- Elimination of Unrealized Profits in Inventory

- Fair-Value Reporting Option for Equity Method Investments

1. The Reporting of Investments in Corporate Equity Securities:

In a recent annual report, JB Hunt Transport Services describes the creation of Transplace, Inc. (TPI), an Internet-based global transportation logistics company. JB Hunt contributed all of its logistics segment business and all related intangible assets plus $5 million of cash in exchange for an approximate 27 percent initial interest in TPI, which subsequently has been increased to 37 percent.

The company accounts for its interest in TPI utilizing the equity method of accounting and stated, “The financial results of TPI are included on a one-line, and non-operating item included on the Consolidated Statements of Earnings entitled ‘equity in earnings of associated companies”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Such information is hardly unusual in the business world; corporate as well as individual investors frequently acquire ownership shares of both domestic and foreign businesses. These investments can range from the purchase of a few shares to the acquisition of 100 percent control.

Although purchases of corporate equity securities (such as the one made by JB Hunt) are not uncommon, they pose a considerable number of financial reporting issues because a close relationship has been established without the investor gaining actual control. These issues are currently addressed by the equity method. It deals with accounting for stock investments that fall under the application of this method.

At present, accounting standards recognize three different approaches to the financial reporting of investments in corporate equity securities:

i. The Fair-Value Method.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. The Consolidation of Financial Statements.

iii. The Equity Method.

The financial statement reporting for a particular investment depends primarily on the degree of influence that the investor (stockholder) has over the investee, a factor typically indicated by the relative size of ownership.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In many instances, an investor possesses only a small percentage of an investee company’s outstanding stock, perhaps only a few shares. Because of the limited level of ownership, the investor cannot expect to significantly affect the investee’s operations or decision making. These shares are bought in anticipation of cash dividends or in appreciation of stock market values.

Such investments are recorded at cost and periodically adjusted to fair value according to the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in its Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 115 (SFAS 115), “Accounting for Certain Investments in Debt and Equity Securities,” May 1993.

Because a full coverage of SFAS 115 is presented in intermediate accounting textbooks, only the following basic principles are noted here:

i. Initial investments in equity securities are recorded at cost and subsequently adjusted to fair value if fair value is readily determinable; otherwise, the investment remains at cost.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

ii. Equity securities held for sale in the short term are classified as trading securities and reported at fair value, with unrealized gains and losses included in earnings.

iii. Equity securities not classified as trading securities are classified as available-for-sale securities and reported at fair value with unrealized gains and losses excluded from earnings and reported in a separate component of shareholders’ equity as part of other comprehensive income.

iv. Dividends received are recognized as income for both trading and available-for-sale securities.

These procedures are required for equity security investments when neither significant influence nor control is present. As will be shown, the procedures for significant influence investments in equity securities, while somewhat complex, adhere more closely to traditional accrual accounting.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Consolidation of Financial Statements:

Many corporate investors acquire enough shares to gain actual control over an investee’s operation. In financial accounting, such control is recognized whenever a stockholder accumulates more than 50 percent of an organization’s outstanding voting stock. At that point, rather than simply influencing the investee’s decisions, the investor clearly can direct the entire decision-making process.

A review of the financial statements of America’s largest organizations indicates that legal control of one or more subsidiary companies is an almost universal practice. PepsiCo, Inc., as just one example, holds a majority interest in the voting stock of literally hundreds of corporations.

Investor control over an investee presents an economic situation not adequately addressed by SFAS 115. Normally, when a majority of voting stock is held, the investor-investee relationship is so closely connected that the two corporations are viewed as a single entity for reporting purposes. Hence, an entirely different set of accounting procedures is applicable.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to SFAS 141R, “Business Combinations,” and SFAS 160, “Non-controlling Interests and Consolidated Financial Statements,” control generally requires the consolidation of the accounting information produced by the individual companies. Thus, a single set of financial statements is created for external reporting purposes with all assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses being brought together.

FASB Interpretation No. 46R, “Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities, an Interpretation of ARB No. 51” (FIN 46R; revised December 2003) expands the use of consolidated financial statements to include entities that are financially controlled through special contractual arrangements rather than through voting stock interests.

Prior to FIN 46R, many firms (e.g., Enron) avoided consolidation of entities in which they owned little or no voting stock but otherwise were controlled through special contracts. These entities were frequently referred to as “special purpose entities (SPEs)” and provided vehicles for some firms to keep large amounts of assets and liabilities off their consolidated financial statements.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Finally, another investment relationship is appropriately accounted for using the equity method. JB Hunt’s ownership of 37 percent of TPI’s voting stock is less than enough to control the voting stock. Despite the lack of voting control, however, JB Hunt maintains a large interest in this investee company. Through its ownership, JB Hunt can undoubtedly affect TPI’s decisions and operations.

Especially important is the investor’s ability to influence the amount and timing of dividend distributions. Because of this influence, the receipt of a dividend from an investee does not qualify as an objective basis for recording income to the investor firm. Thus, to provide an objective basis for reporting investment income, the equity method requires that the investor recognize income as the investee earns it, not when the investor receives dividends.

Because managerial compensation contracts often are based on net income, incentives exist for managers to use whatever discretion they have available in reporting net income. The equity method effectively removes managers’ ability to use their influence over the timing and amounts of investee dividend distributions to increase current income (or defer income to future periods). Accordingly, under the equity method the investor recognizes investee income as it is earned by the investee, not when dividends are received.

In today’s business world, many corporations hold significant ownership interests in other companies without having actual control. The Coca-Cola Company alone owns between 20 and 50 percent of dozens of separate corporations. Many other investments represent joint ventures in which two or more companies form a new enterprise to carry out a specified operating purpose. For example, Microsoft and NBC formed MSNBC, a cable channel and online site to go with NBC’s broadcast network. Each partner owns 50 percent of the joint venture.

For each of these investments, the investors do not possess absolute control because they hold less than a majority of the voting stock. Thus, the preparation of consolidated financial statements is inappropriate. However, the large percentage of ownership indicates that each investor possesses some ability to affect the investee’s decision-making process.

To reflect this relationship, such investments are accounted for by the equity method as officially established by Opinion 18, “The Equity Method of Accounting for Investments in Common Stock,” issued by the Accounting Principles Board (APB) in March 1971 and as amended in 2001 by SFAS 142, “Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In February 2007 the FASB issued Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 159, The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities. This statement allows business entities the option to report many financial assets, including those currently accounted for by the equity method, at their fair values.

2. Accounting for an Investment—the Equity Method

:

Now that the criteria leading to the application of the equity method have been identified, a review of its reporting procedures is appropriate. Knowledge of this accounting process is especially important to users of the investor’s financial statements because the equity method affects both the timing of income recognition as well as the carrying value of the investment account.

In applying the equity method, the accounting objective is to report the investor’s investment and investment income reflecting the close relationship between the companies.

After recording the cost of the acquisition, two equity method entries periodically record the investment’s impact:

i. The investor’s investment account increases as the investee earns and reports income. Also, the investor recognizes investment income using the accrual method—that is, in the same time period as the investee earns it. If an investee reports income of $100,000, a 30 percent owner should immediately increase its own income by $30,000.

This earnings accrual reflects the essence of the equity method by emphasizing the connection between the two companies; as the owners’ equity of the investee increases through the earnings process, so the investment account also increases. Although the investor initially records the acquisition at cost, upward adjustments in the asset balance are recorded as soon as the investee makes a profit. A reduction is necessary if a loss is reported.

ii. The investor’s investment account is decreased whenever a dividend is collected. Because distribution of cash dividends reduces the book value of the investee company, the investor mirrors this change by recording the receipt as a decrease in the carrying value of the investment rather than as revenue. Once again, a parallel is established between the investment account and the underlying activities of the investee.

The reduction in the investee’s owners’ equity creates a decrease in the investment. Furthermore, because the investor immediately recognizes income when the investee earns it, double counting would occur if the investor also recorded subsequent dividend collections as revenue. Importantly, the collection of a cash dividend is not an appropriate point for income recognition. Because the investor can influence the timing of investee dividend distributions, the receipt of a dividend is not an objective measure of the income generated from the investment.

Application of the equity method causes the investment account on the investor’s balance sheet to vary directly with changes in the investee’s equity. As an illustration, assume that an investor acquires a 40 percent interest in a business enterprise. If the investor has the ability to significantly influence the investee, the equity method must be utilized.

If the investee subsequently reports net income of $50,000, the investor increases the investment account (and its own net income) by $20,000 in recognition of a 40 percent share of these earnings. Conversely, a $20,000 dividend collected from the investee necessitates a reduction of $8,000 in this same asset account (40 percent of the total payout).

In contrast, the fair-value method reports investments at fair value if it is readily determinable. Also, income is recognized only on receipt of dividends. Consequently, financial reports can vary depending on whether the equity method or fair-value method is appropriate.

To illustrate, assume that Big Company owns a 20 percent interest in Little Company purchased on January 1, 2008, for $200,000. Little then reports net income of $200,000, $300,000, and $400,000, respectively, in the next three years while paying dividends of $50,000, $100,000, and $200,000. The fair values of Big’s investment in little, as determined by market prices, were $235,000, $255,000, and $320,000 at the end of 2008, 2009, and 2010, respectively.

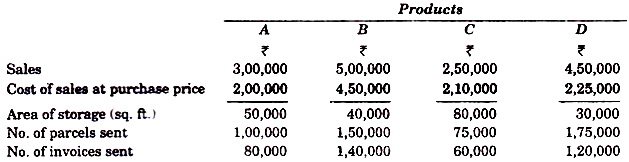

Exhibit 1.1 compares the accounting for Big’s investment in little across the two methods. The fair-value method carries the investment at its market values, presumed to be readily available in this example. Because the investment is classified as an available-for-sale security, the excess of fair value over cost is reported as a separate component of stockholders’ equity. Income is recognized as dividends are received.

In contrast, under the equity method, Big recognizes income as it is earned by little. As shown in Exhibit 1.1, Big recognizes $180,000 in income over the three years, and the carrying value of the investment is adjusted upward to $310,000. Dividends received are not an appropriate measure of income because of the assumed significant influence over the investee.

Big’s ability to influence Little’s decisions applies to the timing of dividend distributions. Therefore, dividends received do not objectively measure Big’s income from its investment in little. As little earns income, however, under the equity method Big recognizes its share (20 percent) of the income and increases the investment account. The equity method reflects the accrual model: Income is recognized as it is earned, not when cash (dividend) is received.

Exhibit 1.1 shows that the carrying value of the investment fluctuates each year under the equity method. This recording parallels the changes occurring in the net asset figures reported by the investee. If the owner’s equity of the investee rises through income, an increase is made in the investment account; decreases such as losses and dividends cause reductions to be recorded. Thus, the equity method conveys information that describes the relationship created by the investor’s ability to significantly influence the investee.

3. Accounting Procedures Used in Applying the Equity Method

:

Once guidelines for the application of the equity method have been established, the mechanical process necessary for recording basic transactions is quite straightforward. The investor accrues its percentage of the earnings reported by the investee each period. Dividend declarations reduce the investment balance to reflect the decrease in the investee’s book value.

Referring again to the information presented in Exhibit 1.1, Little Company reported a net income of $200,000 during 2008 and paid cash dividends of $50,000. These figures indicate that Little’s net assets have increased by $150,000 during the year.

Therefore, in its financial records, Big Company records the following journal entries to apply the equity method:

In the first entry, Big accrues income based on the investee’s reported earnings even though this amount greatly exceeds the cash dividend. The second entry reflects the actual receipt of the dividend and the related reduction in Little’s net assets. The $30,000 net increment recorded here in Big’s investment account ($40,000 — $10,000) represents 20 percent of the $150,000 increase in Little’s book value that occurred during the year.

Although these two entries illustrate the basic reporting process used in applying the equity method, several other issues must be explored to obtain a full understanding of this approach.

More specifically, special procedures are required in accounting for each of the following:

1. Reporting a change to the equity method.

2. Reporting investee income from sources other than continuing operations.

3. Reporting investee losses.

4. Reporting the sale of an equity investment.

1. Reporting a Change to the Equity Method:

In many instances, an investor’s ability to significantly influence an investee is not achieved through a single stock acquisition. The investor could possess only a minor ownership for some years before purchasing enough additional shares to require conversion to the equity method.

Before the investor achieves significant influence, any investment should be reported by the fair-value method. After the investment reaches the point at which the equity method becomes applicable, a technical question arises about the appropriate means of changing from one method to the other.

APB Opinion 18 addresses this concern by stating that “the investment, results of operations (current and prior periods presented), and retained earnings of the investor should be adjusted retroactively.” Thus, all accounts are restated so that the investor’s financial statements appear as if the equity method had been applied from the date of the first acquisition.

By mandating retrospective treatment, the APB attempted to ensure comparability from year to year in the financial reporting of the investor company. For example, Frequency Electronics, a firm that specializes in designing, developing, and manufacturing satellite communications equipment, recently reported an increase in its stock ownership of Morion, Inc., a crystal oscillator manufacturer located in St. Petersburg, Russia.

To further illustrate this restatement procedure, assume that Giant Company acquires a 10 percent ownership in Small Company on January 1, 2008. Officials of Giant do not believe that their company has gained the ability to exert significant influence over Small. Giant properly records the investment by using the fair-value method as an available-for-sale security. Subsequently, on January 1,2010, Giant purchases an additional 30 percent of the Small’s outstanding voting stock, thereby achieving the ability to significantly influence the investee’s decision making.

From 2008 through 2010, Small reports net income, pays cash dividends, and has fair values at January 1 of each year as follows:

In Giant’s 2008 and 2009 financial statements, as originally reported, dividend revenue of $2,000 and $4,000, respectively, would be recognized based on receiving 10 percent of these distributions. The investment account is maintained at fair value because it is readily determinable.

Also, the change in the investment’s fair value results in a credit to an unrealized cumulative holding gain of $4,000 in 2008 and an additional credit of $9,000 in 2009 for a cumulative amount of $13,000 reported in Giant’s 2009 stockholders’ equity section.

However, after changing to the equity method on January 1, 2010, Giant must restate these prior years to present the investment as if the equity method had always been applied. Subsequently, in comparative statements showing columns for previous periods, the 2008 statements should indicate equity income of $7,000 with $11,000 being disclosed for 2009 based on a 10 percent accrual of Small’s income for each of these years.

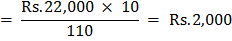

The income restatement for these earlier years can be computed as follows:

Giant’s reported earnings for 2008 will increase by $5,000 with a $7,000 increment needed for 2009. To bring about this retrospective change to the equity method.

Giant prepares the following journal entry on January 1, 2010:

The $13,000 adjustment removes the accounts required by SFAS 115 that pertain to the investment prior to obtaining significant influence. Because the investment is no longer part of the available-for-sale portfolio, it is carried under the equity method rather than at fair value. Accordingly, the fair-value adjustment accounts are reduced as part of the reclassification.

Continuing with this example, Giant makes two other journal entries at the end of 2010, but they relate solely to the operations and distributions of that period.

2. Reporting Investee Income from Sources Other than Continuing Operations:

Traditionally, certain elements of income are presented separately within a set of financial statements. Examples include extraordinary items (APB Opinion 30, “Reporting the Results of Operations,” June 1973) and prior period adjustments (FASB SFAS 16, “Prior Period Adjustments,” June 1977). A concern that arises in applying the equity method is whether items appearing separately in the investee’s income statement require similar treatment by the investor.

To examine this issue, assume that Large Company owns 40 percent of the voting stock of Tiny Company and accounts for this investment by means of the equity method. In 2008, Tiny reports net income of $200,000, a figure composed of $250,000 in income from continuing operations and a $50,000 extraordinary loss. Large Company accrues earnings of $80,000 based on 40 percent of the $200,000 net figure.

However, for proper disclosure, the extraordinary loss incurred by the investee must also be reported separately on the financial statements of the investor. This handling is intended, once again, to mirror the close relationship between the two companies.

Based on the level of ownership, Large recognizes $100,000 as a component of operating income (40 percent of Tiny Company’s $250,000 income from continuing operations) along with a $20,000 extraordinary loss (40 percent of $50,000). The overall effect is still an $80,000 net increment in Large’s earnings, but this amount has been appropriately allocated between income from continuing operations and extraordinary items.

The journal entry to record Large’s equity interest in the income of Tiny follows:

One additional aspect of this accounting should be noted. Even though the investee has already judged this loss as extraordinary. Large does not report its $20,000 share as a separate item unless that figure is considered to be material with respect to the investor’s own operations.

Although most of the previous illustrations are based on the recording of profits, accounting for losses incurred by the investee is handled in a similar manner. The investor recognizes the appropriate percentage of each loss and reduces the carrying value of the investment account. Even though these procedures are consistent with the concept of the equity method, they fail to take into account all possible loss situations.

APB Opinion 18 recognizes that investments can suffer permanent losses in fair value that are not properly reflected through the equity method. Such declines can be caused by the loss of major customers, changes in economic conditions, loss of a significant patent or other legal right, damage to the company’s reputation, and the like. Permanent reductions in fair value resulting from such adverse events might not be reported immediately by the investor through the normal equity entries.

Thus, when a permanent decline in an equity method investment’s value occurs, the investor must recognize an impairment loss and reduce the asset to fair value. However, APB Opinion 18 stresses that this loss must be permanent before such recognition becomes necessary. Under the equity method, a temporary drop in the fair value of an investment is simply ignored.

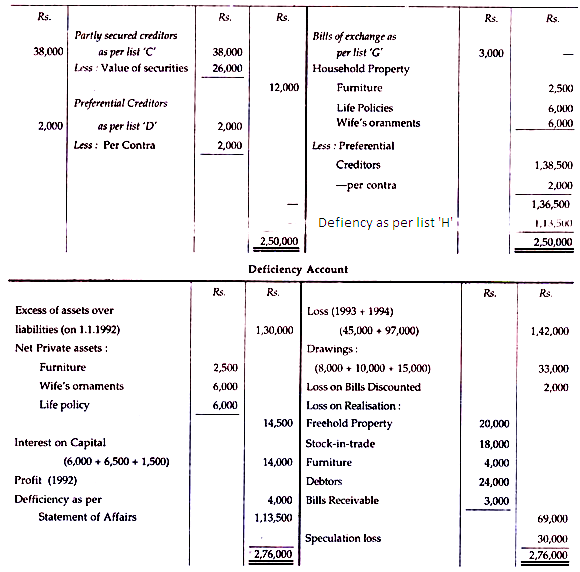

Through the recognition of reported losses as well as any permanent drops in fair value, the investment account can eventually be reduced to a zero balance. This condition is most likely to occur if the investee has suffered extreme losses or if the original purchase was made at a low, bargain price. Regardless of the reason, the carrying value of the investment account could conceivably be eliminated in total.

When an investment account is reduced to zero, the investor should discontinue using the equity method rather than establish a negative balance. The investment retains a zero balance until subsequent investee profits eliminate all unrealized losses. Once the original cost of the investment has been eliminated, no additional losses can accrue to the investor (since the entire cost has been written off) unless some further commitment has been made on behalf of the investee.

4. Reporting the Sale of an Equity Investment:

At any time, the investor can choose to sell part or all of its holdings in the investee company. If a sale occurs, the equity method continues to be applied until the transaction date, thus establishing an appropriate carrying value for the investment. The investor then reduces this balance by the percentage of shares being sold.

As an example, assume that Top Company owns 40 percent of the 100,000 outstanding shares of Bottom Company, an investment accounted for by the equity method. Although these 40,000 shares were acquired some years ago for $200,000, application of the equity method has increased the asset balance to $320,000 as of January 1, 2008. On July 1, 2008, Top elects to sell 10,000 of these shares (one-fourth of its investment) for $110,000 in cash, thereby reducing ownership in Bottom from 40 percent to 30 percent. Bottom Company reports income of $70,000 during the first six months of 2008 and distributes cash dividends of $30,000.

Top, as the investor, initially makes the following journal entries on July 1, 2008, to accrue the proper income and establish the correct investment balance:

These two entries increase the carrying value of Top’s investment by $16,000, creating a balance of $336,000 as of July 1, 2008.

The sale of one-fourth of these shares can then be recorded as follows:

After the sale is completed, Top continues to apply the equity method to this investment based on 30 percent ownership rather than 40 percent. However, if the sale had been of sufficient magnitude to cause Top to lose its ability to exercise significant influence over Bottom, the equity method ceases to be applicable. For example, if Top Company’s holdings were reduced from 40 percent to 15 percent, the equity method might no longer be appropriate after the sale. The shares still being held are reported according to the fair-value method with the remaining book value becoming the new cost figure for the investment rather than the amount originally paid.

If an investor is required to change from the equity method to the fair-value method, no retrospective adjustment is made. Although, as previously demonstrated, a change to the equity method mandates a restatement of prior periods, the treatment is not the same when the investor’s change is to the fair-value method.

4. Excess of Investment Cost Over Book Value Acquired

:

After the basic concepts and procedures of the equity method are mastered, more complex accounting issues can be introduced. Surely one of the most common problems encountered in applying the equity method concerns investment costs that exceed the proportionate book value of the investee company.

Unless the investor acquires its ownership at the time of the investee’s conception, paying an amount equal to book value is rare. Dell Computer Corporation, as just one example, reported a book value of approximately $1.38 per share on October 31, 2006, but on that date, the company’s common stock traded nearly $24 per share on the NASDAQ Exchange. To obtain Dell Computer shares as well as the stock of many other businesses, payment of a significant premium over book value is required.

A number of possible reasons exist for such a marked difference between the book value of a company and the price of its stock. A company’s value at any time is based on a multitude of factors such as company profitability, the introduction of a new product, expected dividend payments, projected operating results, and general economic conditions.

Furthermore, stock prices are based, at least partially, on the perceived worth of a company’s net assets, amounts that often vary dramatically from underlying book values. Asset and liability accounts shown on a balance sheet tend to measure historical costs rather than current value.

In addition, these reported figures are affected by the specific accounting methods adopted by a company. Inventory costing methods such as LIFO and FIFO, for example, obviously lead to different book values as does each of the acceptable depreciation methods.

If an investment is acquired at a price in excess of book value, logical reasons should explain the additional cost incurred by the investor. The source of the excess of cost over book value is important. Income recognition requires matching the income generated from the investment with its cost. Excess costs allocated to fixed assets will likely be expensed over longer periods than costs allocated to inventory.

In applying the equity method, the cause of such an excess payment can be divided into two general categories:

1. Specific investee assets and liabilities can have fair values that differ from their present book values. The excess payment can be identified directly with individual accounts such as inventory, equipment, franchise rights, and so on.

2. The investor could be willing to pay an extra amount because future benefits are expected to accrue from the investment. Such benefits could be anticipated as the result of factors such as the estimated profitability of the investee or the relationship being established between the two companies.

In this case, the additional payment is attributed to an intangible future value generally referred to as goodwill rather than to any specific investee asset or liability. For example, in a recent annual report, Ameritech Corporation disclosed that its long-term investment in Tele Danmark, accounted for under the equity method, includes goodwill of approximately $1.4 billion.

As an illustration, assume that Big Company is negotiating the acquisition of 30 percent of the outstanding shares of Little Company. Little’s balance sheet reports assets of $500,000 and liabilities of $300,000 for a net book value of $200,000. After investigation, Big determines that Little’s equipment is undervalued in the company’s financial records by $60,000.

One of its patents is also undervalued, but only by $40,000. By adding these valuation adjustments to Little’s book value, Big arrives at an estimated $300,000 worth for the company’s net assets. Based on this computation, Big offers $90,000 for a 30 percent share of the investee’s outstanding stock.

Although Big’s purchase price is in excess of the proportionate share of Little’s book value, this additional amount can be attributed to two specific accounts: Equipment and Patents. No part of the extra payment is traceable to any other projected future benefit.

Thus, the cost of Big’s investment is allocated as follows:

Of the $30,000 excess payment made by the investor, $18,000 is assigned to the equipment whereas $12,000 is traced to a patent and its undervaluation. No amount of the purchase price is allocated to goodwill.

To take this example one step further, assume that Little’s owners reject Big’s proposed $90,000 price. They believe that the value of the company as a going concern is higher than the fair value of its net assets. Because the management of Big believes that valuable synergies will be created through this purchase, the bid price is raised to $125,000 and accepted.

This new acquisition price is allocated as follows:

As this example indicates, any extra payment that cannot be attributed to a specific asset or liability is assigned to the intangible asset goodwill. Although the actual purchase price can be computed by a number of different techniques or simply result from negotiations, goodwill is always the excess amount not allocated to identifiable asset or liability accounts.

Under the equity method, the investor enters total cost in a single investment account regardless of the allocation of any excess purchase price. If all parties accept Big’s bid of $125,000, the acquisition is initially recorded at that amount despite the internal assignments made to equipment, patents, and goodwill. The entire $125,000 was paid to acquire this investment, and it is recorded as such.

The preceding extra payments were made in connection with specific assets (equipment, patents, and goodwill). Even though the actual dollar amounts are recorded within the investment account, a definite historical cost can be attributed to these assets. With a cost to the investor as well as a specified life, the payment relating to each asset (except goodwill and other indefinite life intangibles) should be amortized over an appropriate time period.

Historically, goodwill implicit in equity method investments had been amortized over periods less than or equal to 40 years. However, in June 2001, the FASB approved a major and fundamental change in accounting for goodwill. SFAS 142, “Goodwill and Other Intangible Assets,” states that for fiscal periods beginning December 15, 2001, and after, the useful life for goodwill is considered indefinite.

Therefore, goodwill amortization expense no longer exists in financial reporting.” Any unamortized portion of implicit goodwill is carried forward without adjustment until the investment is sold or a permanent decline in value occurs.

The FASB noted that goodwill can maintain its value and can even increase over time. The notion of an indefinite life for goodwill recognizes the argument that amortization of goodwill over an arbitrary period fails to reflect economic reality and therefore does not provide useful information. A primary reason for the presumption of an indefinite life for goodwill relates to the accounting for business combinations.

The FASB reasoned that goodwill associated with equity method investments should be accounted for in the same manner as goodwill arising from a business combination. One difference, however, is that goodwill arising from a business combination will be subject to annual impairment reviews, whereas goodwill implicit in equity investments will not. Equity method investments will continue to be tested in their entirety for permanent declines in value.

Assume, for illustrative purposes, that the equipment has a 10-year remaining life, the patent a 5-year life, and the goodwill an indefinite life.

If the straight-line method is used with no salvage value, the investors cost should be amortized initially as follows:

In recording this annual expense, Big is reducing a portion of the investment balance in the same way it would amortize the cost of any other asset that had a limited life.

Therefore, at the end of the first year, the investor records the following journal entry under the equity method:

Because this amortization relates to investee assets, the investor does not establish a specific expense account. Instead, as in the previous entry, the expense is recognized through a decrease in the equity income accruing from the investee company.

To illustrate this entire process, assume that Tall Company purchases 20 percent of Short Company for $200,000. Tall can exercise significant influence over the investee; thus, the equity method is appropriately applied. The acquisition is made on January 1, 2008, when Short holds net assets with a book value of $700,000. Tall believes that the investee’s building (10-year life) is undervalued within the financial records by $80,000 and equipment with a 5-year life is undervalued by $120,000.

Any goodwill established by this purchase is considered to have an indefinite life. During 2008, Short reports a net income of $150,000 and pays a cash dividend at year’s end of $60,000.

Tail’s three basic journal entries for 2008 pose little problem:

An allocation of Tail’s $200,000 purchase price must be made to determine whether an additional adjusting entry is necessary to recognize annual amortization associated with the extra payment:

As can be seen, $16,000 of the purchase price is assigned to a building, $24,000 to equipment, with the remaining $20,000 attributed to goodwill. For each asset with a definite useful life, periodic amortization is required.

At the end of 2008, Tall must also record the following adjustment in connection with these cost allocations:

Although these entries are shown separately here for better explanation. Tall would probably net the income accrual for the year ($30,000) and the amortization ($6,400) to create a single entry increasing the investment and recognizing equity income of $23,600. Thus, the first-year return on Tall Company’s beginning investment balance (defined as equity earnings/beginning investment balance) is equal to 11.80 percent ($23,600/$200,000).

5. Elimination of Unrealized Profits in Inventory

:

Many equity acquisitions establish ties between companies to facilitate the direct purchase and sale of inventory items. Such intercompany transactions can occur either on a regular basis or only sporadically. For example, The Coca-Cola Company recently disclosed that it sold $5,125 billion of syrup and concentrate to its 36 percent-owned investee Coca-Cola Enterprises, Inc.

Regardless of their frequency, inventory sales between investor and investee necessitate special accounting procedures to ensure proper timing of revenue recognition. An underlying principle of accounting is that “revenues are not recognized until earned and revenues are considered to have been earned when the entity has substantially accomplished what it must do to be entitled to the benefits represented by the revenues.” In the sale of inventory to an unrelated party, recognition of revenue is normally not in question; substantial accomplishment is achieved when the exchange takes place unless special terms are included in the contract.

Unfortunately, the earning process is not so clearly delineated in sales made between related parties. Because of the relationship between investor and investee, the seller of the goods is said to retain a partial stake in the inventory for as long as the buyer holds it. Thus, the earning process is not considered complete at the time of the original sale. For proper accounting, income recognition must be deferred until substantial accomplishment is proven.

Consequently, when the investor applies the equity method, reporting of the related profit on intercompany transfers is delayed until the buyer’s ultimate disposition of the goods. When the inventory is eventually consumed within operations or resold to an unrelated party, the original sale is culminated and the gross profit is fully recognized.

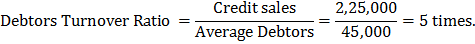

In accounting, transactions between related companies are identified as either downstream or upstream. Downstream transfers refer to the investor’s sale of an item to the investee. Conversely, an upstream sale describes one that the investee makes to the investor (see Exhibit 1.2).

Although the direction of intercompany sales does not affect reported equity method balances for investments when significant influence exists, it has definite consequences when financial control requires the consolidation of financial statements. Therefore, these two types of intercompany sales are examined separately even at this introductory stage.

Downstream Sales of Inventory:

Assume that Big Company owns a 40 percent share of Little Company and accounts for this investment through the equity method. In 2008, Big sells inventory to little at a price of $50,000. This figure includes a markup of 30 percent, or $15,000. By the end of 2008, little has sold $40,000 of these goods to outside parties while retaining $10,000 in inventory for sale during the subsequent year.

The investor has made downstream sales to the investee. In applying the equity method, recognition of the related profit must be delayed until the buyer disposes of these goods. Although total intercompany transfers amounted to $50,000 in 2008, $40,000 of this merchandise has already been resold to outsiders, thereby justifying the normal reporting of profits. For the $10,000 still in the investee’s inventory, the earning process is not finished. In computing equity income, this portion of the intercompany profit must be deferred until little disposes of the goods.

The markup on the original sale was 30 percent of the transfer price; therefore, Big’s profit associated with these remaining items is $3,000 ($10,000 × 30%). However, because only 40 percent of the investee stock is held, just $1,200 ($3,000 × 40%) of this profit is unearned. Big’s ownership percentage reflects the intercompany portion of the profit. The total $3,000 gross profit within the ending inventory balance is not the amount deferred. Rather, 40 percent of that gross profit is viewed as the currently unrealized figure.

After calculating the appropriate deferral, the investor decreases current equity income by $1,200 to reflect the unearned portion of the intercompany profit. This procedure temporarily removes this portion of the profit from the investor’s books in 2008 until the investee disposes of the inventory in 2009.

Big accomplishes the actual deferral through the following year-end journal entry:

In the subsequent year, when this inventory is eventually consumed by little or sold to unrelated parties, the deferral is no longer needed. The earning process is complete, and Big should recognize the $1,200. By merely reversing the preceding deferral entry, the accountant succeeds in moving the investor’s profit into the appropriate time period. Recognition shifts from the year of transfer to the year in which the earning process is substantially accomplished.

Unlike consolidated financial statements, the equity method reports upstream sales of inventory in the same manner as downstream sales. Hence, unrealized profits remaining in ending inventory are deferred until the items are used or sold to unrelated parties.

To illustrate, assume that Big Company once again owns 40 percent of Little Company. During the current year, little sells merchandise costing $40,000 to Big for $60,000. At the end of the fiscal period, Big still retains $15,000 of these goods. Little reports net income of $120,000 for the year.

To reflect the basic accrual of the investee’s earnings. Big records the following journal entry at the end of this year:

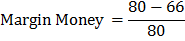

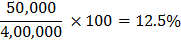

The amount of the gross profit remaining unrealized at year-end is computed using the markup of 33⅓ percent of the sales price ($20,000/$60,000):

Based on this calculation, a second entry is required of the investor at year-end. Once again, a deferral of the unrealized gross profit created by the intercompany transfer is necessary for proper timing of income recognition. Under the equity method for investments with significant influence, the direction of the sale between the investor and investee (upstream or downstream) has no effect on the final amounts reported in the financial statements.

After the adjustment, Big, the investor, reports earnings from this equity investment of $46,000 ($48,000 — $2,000). The income accrual is reduced because a portion of the intercompany gross profit is considered unrealized. When the investor eventually consumes or sells the $15,000 in merchandise, the preceding journal entry is reversed. In this way, the effects of the transfer are reported in the proper accounting period when the profit is earned by sales to an outside party.

In an upstream sale, the investor’s own inventory account contains the unrealized profit. The previous entry, though, defers recognition of this profit by decreasing Big’s investment account rather than the inventory balance. APB Accounting Interpretation No. 1 of APB Opinion 18, “Intercompany Profit Eliminations under Equity Method,” November 1971, permits the direct reduction of the investor’s inventory balance as a means of accounting for this unrealized amount. Although this alternative is acceptable, decreasing the investment remains the traditional approach for deferring unrealized gross profits, even for upstream sales.

Whether upstream or downstream, the investor’s sales and purchases are still reported as if the transactions were conducted with outside parties. Only the unrealized gross profit is deferred, and that amount is adjusted solely through the equity income account. Furthermore, because the companies are not consolidated, the investee’s reported balances are not altered at all to reflect the nature of these sales/purchases.

Obviously, readers of the financial statements need to be made aware of the inclusion of these amounts in the income statement. Thus, the FASB issued Statement No. 57, “Related Party Disclosures,” in March 1982; it required reporting companies to disclose certain information about related-party transactions. These disclosures include the nature of the relationship, a description of the transactions, the dollar amounts of the transactions, and amounts due to or from any related parties at year-end.

Decision Making and the Equity Method:

It is important to realize that business decisions, including equity investments, typically involve the assessment of a wide range of consequences. For example, managers frequently are very interested in how financial statements report the effects of their decisions.

This attention to financial reporting effects of business decisions arises because measurements of financial performance often affect the following:

i. The firm’s ability to raise capital.

ii. Managerial compensation.

iii. The ability to meet debt covenants and future interest rates.

iv. Managers’ reputations.

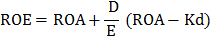

Managers are also keenly aware that measures of earnings per share can strongly affect investors’ perceptions of the underlying value of their firms’ publicly traded stock. Consequently, prior to making investment decisions, firms will study and assess the prospective effects of applying the equity method on the income reported in financial statements.

Additionally, such analyses of prospective reported income effects can influence firms regarding the degree of influence they wish to have or even on the decision of whether to invest. For example, managers could have a required projected rate of return on an initial investment. In such cases, an analysis of projected income will be made to assist in setting an offer price.

For example, Investmor Co. is examining a potential 25 percent equity investment in Marco, Inc., that will provide a significant level of influence. Marco projects an annual income of $300,000 for the near future. Marco’s book value is $450,000, and it has an unrecorded newly developed technology appraised at $200,000 with an estimated useful life of 10 years.

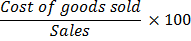

In considering offer prices for the 25 percent investment in Marco, Investor projects equity earnings as follows:

Investor’s required first-year rate of return (before tax) on these types of investments is 20 percent. Therefore, to meet the first-year rate of return requirement involves a maximum price of $350,000 ($70,000/20% = $350,000). If the shares are publicly traded (leaving the firm a “price taker”), such income projections can assist the company in making a recommendation to wait for share prices to move to make the investment attractive.

Criticisms of the Equity Method:

In the past several decades since APB Opinion 18, thousands of business firms have accounted for their investments using the equity method.

Recently, however, the equity method has come under criticism for the following:

i. Emphasizing the 20-50 percent of voting stock in determining significant influence versus control.

ii. Allowing off-balance sheet financing.

iii. Potentially biasing performance ratios.

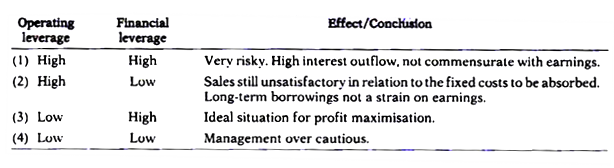

The guidelines for the equity method suggest that a 20-50 percent ownership of voting shares indicates significant influence that falls short of control. But can one firm exert “control” over another firm absent an interest of more than 50 percent? Clearly, if one firm controls another, consolidation is the appropriate financial reporting technique.

However, over the years, firms have learned ways to control other firms despite owning less than 50 percent of voting shares. For example, contracts across companies can limit one firm’s ability to act without permission of the other. Such contractual control can be seen in debt arrangements, long-term sales and purchase agreements, and agreements concerning board membership. As a result, control is exerted through a variety of contractual arrangements. For financial reporting purposes, however, if ownership is 50 percent or less, a firm can argue that control technically does not exist.

In contrast to consolidated financial reports, when applying the equity method, the investee’s assets and liabilities are not combined with the investor’s amounts. Instead, the investor’s balance sheet reports a single amount for the investment and the income statement reports a single amount for its equity in the earnings of the investee. If consolidated, the assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses of the investee are combined and reported in the body of the investor’s financial statements.

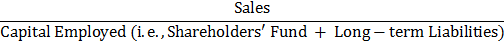

Thus, for those companies wishing to actively manage their reported balance sheet numbers, the equity method provides an effective means. By keeping its ownership of voting shares below 50 percent, a company can technically meet the rules for applying the equity method for its investments and at the same time report investee assets and liabilities “off balance sheet.” As a result, relative to consolidation, a firm employing the equity method will report smaller values for assets and liabilities. Consequently, higher rates of return for its assets and sales, as well as lower debt-to-equity ratios, could result.

On the surface, it appears that firms can avoid balance sheet disclosure of debts by maintaining investments at less than 50 percent ownership. However, APB 18 requires “summarized information as to assets, liabilities, and results of operations of the investees to be presented in the notes or in separate statements, either individually or in groups, as appropriate.”

Therefore, supplementary information could be available under the equity method that would not be separately identified in consolidation. Nonetheless, some companies have contractual provisions (e.g., debt covenants, managerial compensation agreements) based on ratios in the main body of the financial statements. Meeting the provisions of such contracts could provide managers strong incentives to maintain technical eligibility to use the equity method rather than full consolidation.

6. Fair-Value Reporting Option for Equity Method Investments

:

In February 2007, the FASB issued Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No.-159 (SFAS 159). “The Fair Value Option for Financial Assets and Financial Liabilities.” The statement creates a fair-value option under which an entity may irrevocably elect fair value as the initial and subsequent measurement attribute for certain financial assets and financial liabilities.

Under the fair-value option, changes in the fair value of the elected financial items would be included in earnings. Among the many financial assets available for the fair-value option include investments currently accounted for under the equity method. SFAS 159 underscores the FASB’s emphasis on fair values for financial reporting.

The Board believes that fair values for financial assets and financial liabilities provide more relevant and understandable information than cost or cost-based measures. In particular, the Board believes that fair value is more relevant to financial statement users than cost for assessing the current financial position of an entity because fair value reflects the current cash equivalent of the entity’s financial instruments rather than the price of a past transaction. The Board also believes that, with the passage of time, historical prices become irrelevant in assessing an entity’s current financial position.

Firms that employ the equity method may elect to switch to fair value in reporting these investments. However, such an election would be irrevocable, leaving the firm no option to switch back to the equity method. Under the fair-value option, firms simply report the investment’s fair value as an asset and any changes in its fair value as earnings.

Although not specifically stated, dividends received from an investee presumably also are included in earnings under the fair-value option. Because dividends typically reduce an investment’s fair value, an increase in earnings from dividends would be offset by a decrease in earnings from a decline in the investment’s fair value.

In addition to the increasing emphasis on fair values in financial reporting, the fair-value option also is motivated by a perceived need for consistency across various balance sheet items. In particular, the fair-value option is designed to limit volatility in earnings that occurs when some financial items are measured using cost-based attributes and others at fair value.

SFAS 159 also provides a fair-value reporting option for available-for-sale and held-to-maturity securities currently accounted for under SFAS 115, “Accounting for Certain Investments in Debt and Equity Securities.” However, consolidated investments are specifically excluded from the statement’s scope. The fair-value election will be available for financial reporting in 2008.