In this article we will discuss about:- 1. Consolidation the Effects Created by the Passage of Time 2. Investment Accounting by the Acquiring Company 3. Subsequent Consolidation—Investment Recorded by the Equity Method 4. Subsequent Consolidation Investment Recorded Using Initial Value or Partial Equality Method 5. Contingent Consideration 6. Push-Down Accounting.

Contents:

- Consolidation the Effects Created by the Passage of Time

- Investment Accounting by the Acquiring Company

- Subsequent Consolidation—Investment Recorded by the Equity Method

- Subsequent Consolidation Investment Recorded Using Initial Value or Partial Equality Method

- Contingent Consideration

- Push-Down Accounting

1. Consolidation the Effects Created by the Passage of Time

:

Despite complexities created by the passage of time, the basic objective of all consolidations remains the same- to combine asset, liability, revenue, expense, and equity accounts of a parent and its subsidiaries. From a mechanical perspective, a worksheet and consolidation entries continue to provide structure for the production of a single set of financial statements for the combined business entity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The time factor introduces additional complications into the consolidation process. For internal record-keeping purposes, the parent must select and apply an accounting method to monitor the relationship between the two companies. The investment balance recorded by the parent varies over time as a result of the method chosen, as does the income subsequently recognized.

These differences affect the periodic consolidation process but not the figures to be reported by the combined entity. Regardless of the amount, the parent’s investment account is eliminated on the worksheet so that the subsidiary’s actual assets and liabilities can be consolidated. Likewise, the income figure accrued by the parent is removed each period so that the subsidiary’s revenues and expenses can be included when creating an income statement for the combined business entity.

2. Investment Accounting by the Acquiring Company

:

For external reporting, consolidation of a subsidiary becomes necessary whenever control exists. For internal record-keeping, though, the parent has the choice of three alternatives for monitoring the activities of its subsidiaries; the initial value method, the equity method, or the partial equity method.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Because both the resulting investment balance and the related income are eliminated as part of every recurring consolidation, the selection of a particular method does not affect the totals ultimately reported for the combined companies. However, this decision does lead to distinct procedures subsequently utilized in consolidating the financial information of the separate organizations.

For any particular combination, each of the alternative investment accounting methods (initial value, equity, and partial equity methods) begins with an identical value recorded at the date of acquisition. Prior to SFAS 141R, the value assigned to the investment account was cost for a purchase acquisition.

However, the SFAS 141R acquisition method now requires a newly acquired subsidiary to be recorded using fair values, not costs. Typically the fair value of the consideration transferred by the parent (or its share of the fair value of the net amount of the assets acquired and liabilities assumed in a bargain purchase) will serve as the valuation basis on the parent’s books.

Consequently, the way we assign an initial value to the parent’s investment account will depend on when the acquisition occurred as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. For pre-SFAS 141R combinations, the parent recorded the investment account at its cost as measured by the purchase method or the subsidiary’s book value for a pooling of interests.

ii. For post—5K4S 141R combinations, the parent records the investment account using its share of the subsidiary fair value recognized at acquisition (usually the fair value of the consideration transferred by the parent).

In many case the initial fair value of the combination assigned to the investment account will be identical to its cost. But because there will be other cases under SFAS 141R where the two methods will differ, this text uses the new term “initial value” to describe the recording of the combination on the parent’s books.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Subsequent Consolidation—Investment Recorded by the Equity Method

:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Acquisition Made during the Current Year:

As a basis for this illustration, assume that Parrot Company obtains all of the outstanding common stock of Sun Company on January 1, 2009. Parrot acquires this stock for $800,000 in cash.

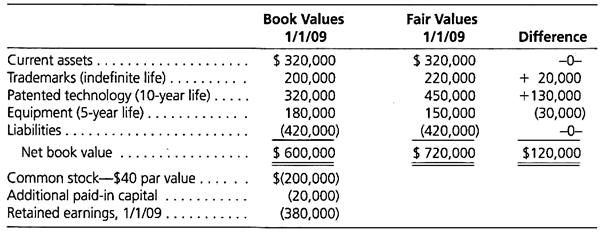

The book values as well as the appraised fair values of Sun’s accounts follow:

Parrot considers the economic life of Sun’s trademarks as extending beyond the foreseeable future and thus having an indefinite life. Following SFAS 142, such assets are not amortized but are subject to periodic impairment testing. For the definite lived assets acquired in the combination (patented technology and equipment), we assume that straight-line amortization with no salvage value is appropriate.

Parrot paid $800,000 cash to acquire Sun Company, clear evidence of the fair value of the consideration transferred. As shown in Exhibit 3.2, individual allocations are used to adjust Sun’s accounts from their book values on January 1, 2009, to fair values. Because the total value of these assets and liabilities was only $720,000, goodwill of $80,000 must be recognized for consolidation purposes.

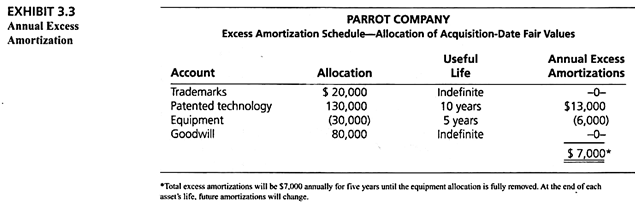

Each of these allocated amounts (other than the $20,000 attributed to trademarks and the $80,000 for goodwill) represents a valuation associated with a definite life. Parrot must amortize each allocation over its expected life. The expense recognition necessitated by this fair value allocation is calculated in Exhibit 3.3.

One aspect of this amortization schedule warrants further explanation. The fair value of Sun’s Equipment account was $30,000 less than book value. Therefore, instead of attributing an additional amount to this asset, the $30,000 allocation actually reflects a fair-value reduction. As such, the amortization shown in Exhibit 3.3 relating to Equipment is not an additional expense but an expense reduction.

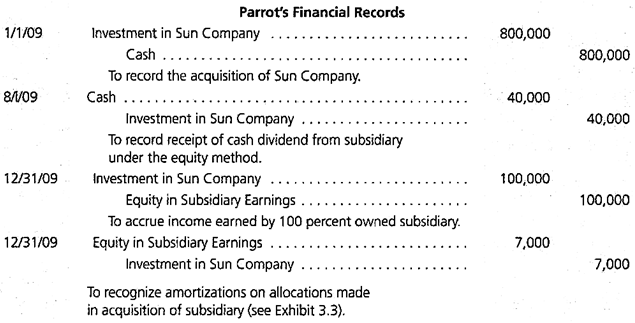

Having determined the allocation of the acquisition-date fair value in the previous example as well as the associated amortization, the parent’s separate record-keeping for 2009 can be constructed. Assume that Sun earns income of $100,000 during the year and pays a $40,000 cash dividend on August 1, 2009.

In this first illustration, Parrot has adopted the equity method. Apparently, this company believes that the information derived from using the equity method is useful in its evaluation of Sun.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Application of the Equity Method:

Parrot’s application of the equity method, as shown in this series of entries, causes the Investment in Sun Company account balance to rise from $800,000 to $853,000 ($800,000 – $40,000 + $100,000 – $7,000). During the same period the parent recognizes a $93,000 equity income figure (the $100,000 earnings accrual less the $7,000 excess amortization expenses).

The consolidation procedures for Parrot and Sun one year after the date of acquisition are illustrated next. For this purpose, Exhibit 3.4 presents the separate 2009 financial statements for these two companies. Parrot recorded both investment-related accounts (the $853,000 asset balance and the $93,000 income accrual) based on applying the equity method.

Determination of Consolidated Totals:

Before becoming immersed in the mechanical aspects of a consolidation, the objective of this process should be understood. In the preparation of consolidated financial reports, the subsidiary’s revenue, expense, asset, and liability accounts are added to the parent company balances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Within this procedure, several important guidelines must be followed:

i. Sun’s assets and liabilities are adjusted to reflect the allocations originating from their acquisition-date fair values.

ii. Because of the passage of time, the income effects (e.g., amortizations) of these allocations must also be recognized within the consolidation process.

iii. Any reciprocal or intercompany accounts must be offset. If, for example, one of the companies owes money to the other, the receivable and the payable balances have no connection with an outside party. Both should be eliminated for external reporting purposes. When the companies are viewed as a single entity, the receivable and the payable are intercompany balances to be removed.

A consolidation of the two sets of financial information in Exhibit 3.4 is a relatively uncomplicated task and can even be carried out without the use of a worksheet. Understanding the origin of each reported figure is the first step in gaining a knowledge of this process.

i. Revenues = $1,900,000. The revenues of the parent and the subsidiary are added together.

ii. Cost of goods sold = $950,000. The cost of goods sold of the parent and subsidiary are added together.

iii. Amortization expense = $153,000. The balances of the parent and of the subsidiary are combined along with the additional amortization from the recognition of the excess fair value over book value attributed to the subsidiary’s patented technology.

iv. Depreciation expense = $104,000. The depreciation expenses of the parent and subsidiary are added together along with the $6,000 reduction in equipment depreciation, as indicated in Exhibit 3.3.

v. Equity in subsidiary earnings = -0-. The investment income recorded by the parent is eliminated so that the subsidiary’s revenues and expenses can be included in the consolidated totals.

vi. Net income = $693,000. Consolidated revenues less consolidated expenses.

vii. Retained earnings, 1/1/09 = $840,000. The parent figure only because the subsidiary was not owned prior to that date.

viii. Dividends paid = $120,000. The parent company balance only because the subsidiary’s dividends were paid intercompany to the parent, not to an outside party.

ix. Retained earnings, 12/31/09 = $1,413,000. Consolidated retained earnings as of the beginning of the year plus consolidated net income less consolidated dividends paid.

x. Current assets = $1,440,000. The parent’s book value plus the subsidiary’s book value.

xi. Investment in Sun Company = -0-. The asset recorded by the parent is eliminated so that the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities can be included in the consolidated totals.

xii. Trademarks = $820,000. The parent’s book value plus the subsidiary’s book value plus the $20,000 acquisition-date fair value allocation.

xiii. Patented technology — $775,000. The parent’s book value plus the subsidiary’s book value plus the $130,000 acquisition-date fair value allocation less current year amortization of $13,000.

xiv. Equipment = $446,000. The parent’s book value plus the subsidiary’s book value less the $30,000 fair value reduction allocation plus the current year expense reduction of $6,000.

xv. Goodwill = $80,000. The residual allocation shown in Exhibit 3.2. Note that goodwill is not amortized.

xvi. Total assets = $3,561,000. A vertical summation of consolidated assets.

xvii. Liabilities = $1,428,000. The parent’s book value plus the subsidiary’s book value.

xviii. Common stock = $600,000. The parent’s book value. Subsidiary shares are no longer outstanding.

xix. Additional paid-in capital = $120,000. The parent’s book value. Subsidiary shares are no longer outstanding.

xx. Retained earnings, 12/31/09 = $1,413,000. Computed previously.

xxi. Total liabilities and equities = $3,561,000. A vertical summation of consolidated liabilities and equities.

Although the consolidated figures to be reported can be computed as just shown, accountants normally prefer to use a worksheet. A worksheet provides an organized structure for this process, a benefit that becomes especially important in consolidating complex combinations.

For Parrot and Sun, only five consolidation entries are needed to arrive at the same figures previously derived for this business combination. Worksheet entries are the catalyst for developing totals to be reported by the entity but are not physically recorded in the individual account balances of either company.

As shown in Exhibit 3.2, Parrot’s $800,000 Investment account balance reflects two components- (1) a $600,000 amount equal to Sun’s book value and (2) a $200,000 figure attributed to the difference, at January 1,2009, between the book value and fair value of Sun’s assets and liabilities (with a residual allocation made to goodwill). Entry S removes the $600,000 component of the Investment in Sun Company account so that the book value of each subsidiary asset and liability can be included in the consolidated figures.

A second worksheet entry (Entry A) eliminates the remaining $200,000 portion of the January 1,2009, Investment in Sun account, allowing the specific allocations to be included along with any goodwill.

Entry S also removes Sun’s stockholders’ equity accounts as of the beginning of the year. Subsidiary equity balances generated prior to the acquisition are not relevant to the business combination and should be deleted. The elimination is made through this entry because the equity accounts and the $600,000 component of the investment account represent reciprocal balances. Both provide a measure of Sun’s book value as of January 1, 2009.

Before moving to the next consolidation entry, a clarification point should be made. In actual practice, worksheet entries are usually identified numerically. However, the label “Entry S” used in this example refers to the elimination of Sun’s beginning Stockholders’ Equity. As a reminder of the purpose being served all worksheet entries are identified in a similar fashion. Thus, throughout this textbook, “Entry S” always refers to the removal of the subsidiary’s beginning stockholders’ equity balances for the year against the book value portion of the investment account.

Consolidation Entry A:

Consolidation entry A adjusts the subsidiary balances from their book values to acquisition-date fair values (see Exhibit 3.2). This entry is labeled “Entry A” to indicate that it represents the Allocations made in connection with the excess of the subsidiary’s fair values over its book values. Sun’s accounts are adjusted collectively by the $200,000 excess of Sun’s $800,000 acquisition-date fair value over its $600,000 book value.

Consolidation Entry I:

“Entry I” (for Income) removes the subsidiary income recognized by Parrot during the year so that Sun’s underlying revenue and expense accounts (and the current amortization expense) can be brought into the consolidated totals. The $93,000 figure eliminated here represents the $100,000 income accrual recognized by Parrot, reduced by the $7,000 in excess amortizations. For consolidation purposes, the one-line amount appearing in the parent’s records is not appropriate and is removed so that the individual revenues and expenses can be included. The entry originally recorded by the parent is simply reversed on the worksheet to remove its impact.

The dividends distributed by the subsidiary during 2009 also must be eliminated from the consolidated totals. The entire $40,000 payment was made to the parent so that, from the viewpoint of the consolidated entity, it is simply an intercompany transfer of cash. The distribution did not affect any outside party.

Therefore, “Entry D” (for Dividends) is designed to offset the impact of this transaction by removing the subsidiary’s Dividends Paid account. Because the equity method has been applied, Parrot’s receipt of this money was recorded originally as a decrease in the Investment in Sun Company account. To eliminate the impact of this reduction, the investment account is increased.

This final worksheet entry records the current year’s excess amortization expenses relating to the adjustments of Sun’s assets to acquisition-date fair values. Because the equity method amortization was eliminated within Entry I, “Entry E” (for Expense) now records the 2009 expense attributed to each of the specific account allocations (see Exhibit 3.3). Note that we adjust depreciation expense for the tangible asset equipment and we adjust amortization expense for the intangible asset patented technology.

As a matter of custom, we refer to the adjustments to all expenses resulting from excess acquisition-date fair value allocations collectively as excess amortization expenses.

Thus, the worksheet entries necessary for consolidation when the parent has applied the equity method are as follows:

Entry S:

Eliminates the subsidiary’s stockholders’ equity accounts as of the beginning of the current year along with the equivalent book value component within the parent’s investment account.

Entry A:

Recognizes the unamortized allocations as of the beginning of the current year associated with the original adjustments to fair value.

Entry I:

Eliminates the impact of intercompany income accrued by the parent.

Entry D:

Eliminates the impact of intercompany dividend payments made by the subsidiary.

Entry E:

Recognizes excess amortization expenses for the current period on the allocations from the original adjustments to fair value.

Exhibit 3.5 provides a complete presentation of the December 31, 2009, consolidation worksheet developed for Parrot Company and Sun Company. The series of entries just described successfully brings together the separate financial statements of these two organizations. Note that the consolidated totals are the same as those computed previously for this combination.

Note that Parrot separately reports net income of $693,000 as well as ending retained earnings of $1,413,000, figures that are identical to the totals generated for the consolidated entity. However, subsidiary income earned after the date of acquisition is to be added to that of the parent. Thus, a question arises in this example as to why the parent company figures alone equal the consolidated balances of both operations.

In reality, Sun’s income for this period is contained in both Parrot’s reported balances and the consolidated totals. Through the application of the equity method the 2009 earnings of the subsidiary have already been accrued by Parrot along with the appropriate amortization expense.

The parent’s Equity in Subsidiary Earnings account is, therefore, an accurate representation of Sun’s effect on consolidated net income. If the equity method is employed properly, the worksheet process simply replaces this single $93,000 balance with the specific revenue and expense accounts that it represents. Consequently, when the parent employs the equity method, its net income and retained earnings mirror consolidated totals.

Consolidation Subsequent to Year of Acquisition—Equity Method:

In many ways, every consolidation of Parrot and Sun prepared after the date of acquisition incorporates the same basic procedures. However, the continual financial evolution undergone by the companies prohibits an exact repetition of the consolidation entries demonstrated in Exhibit 3.5.

As a basis for analyzing the procedural changes necessitated by the passage of time, assume that Parrot Company continues to hold its ownership of Sun Company as of December 31, 2012. This date was selected at random; any date subsequent to 2009 would serve equally well to illustrate this process. As an additional factor, assume that Sun now has a $40,000 liability that is payable to Parrot.

For this consolidation, assume that the January 1, 2012, Sun Company’s Retained Earnings balance has risen to $600,000. Because that account had a reported total of only $380,000 on January 1, 2009, Sun’s book value apparently has increased by $220,000 during the 2009-2011 period. Although knowledge of individual operating figures in the past is not required Sun’s reported totals help to clarify the consolidation procedures.

For 2012 the current year, we assume that Sun reports net income of $160,000 and pays cash dividends of $70,000. Because it applies the equity method, Parrot recognizes earnings of $160,000. Furthermore, as shown in Exhibit 3.3, amortization expense of $7,000 applies to 2012 and must also be recorded by the parent. Consequently, Parrot reports an Equity in Subsidiary Earnings balance for the year of $153,000 ($160,000 – $7,000).

Although this income figure can be reconstructed with little difficulty, the current balance in the Investment in Sun Company account is more complicated.

Over the years, the initial $800,000 acquisition price has been subjected to adjustments for:

1. The annual accrual of Sun’s income.

2. The receipt of dividends from Sun.

3. The recognition of annual excess amortization expenses.

Exhibit 3.6 analyzes these changes and shows the components of the Investment in Sun Company account balance as of December 31, 2012.

Following the construction of the Investment in Sun Company account, the consolidation worksheet developed in Exhibit 3.7 should be easier to understand. Current figures for both companies appear in the first two columns. The parent’s investment balance and equity income accrual as well as Sun’s income and stockholders’ equity accounts correspond to the information given previously. Worksheet entries are then utilized to consolidate all balances.

Several steps are necessary to arrive at these reported totals. The subsidiary’s assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses are added to those same accounts of the parent. The unamortized portion of the original acquisition-date fair-value allocations are included along with current excess amortization expenses. The investment and equity income balances are both eliminated as are the subsidiary’s stockholders’ equity accounts. Intercompany dividends are removed with the same treatment required for the debt existing between the two companies.

Once again, this first consolidation entry offsets reciprocal amounts representing the subsidiary’s book value as of the beginning of the current year. Sun’s January 1, 2012, stockholders’ equity accounts are eliminated against the book value portion of the parent’s investment account.

Here, though, the amount eliminated is $820,000 rather than the $600,000 shown in Exhibit 3.5 for 2009. Both balances have changed during the 2009-2011 period. Sun’s operations caused a $220,000 increase in retained earnings. Parrot’s application of the equity method created a parallel effect on its Investment in Sun Company account (the income accrual of $330,000 less dividends collected of $110,000).

Although Sun’s Retained Earnings balance is removed in this entry, the income this company earned since the acquisition date is still included in the consolidated figures. Parrot accrues these profits annually through application of the equity method. Thus, elimination of the subsidiary’s entire Retained Earnings is necessary; a portion was earned prior to the acquisition and the remainder has already been recorded by the parent.

Entry S removes these balances as of the first day of 2012 rather than at the end of the year. The consolidation process is made a bit simpler by segregating the effect of preceding operations from the transactions of the current year. Thus, all worksheet entries relate specifically to either the previous years (S and A) or the current period (I, D, E, and P).

Consolidation Entry A:

In the initial consolidation (2009), fair-value allocations amounting to $200,000 were entered, but these balances have now undergone three years of amortization. As computed in Exhibit 3.8, expenses for these prior years totaled $21,000, leaving a balance of $179,000. Allocation of this amount to the individual accounts is also determined in Exhibit 3.8 and reflected in worksheet Entry A. As with Entry S, these balances are calculated as of January 1, 2012, so that the current year expenses can be included separately (in Entry E).

Consolidation Entry I:

As before, this entry eliminates the equity income recorded currently by Parrot ($153,000) in connection with its ownership of Sun. The subsidiary’s revenue and expense accounts are left intact so they can be included in the consolidated figures.

Consolidation Entry D:

This worksheet entry offsets the $70,000 intercompany dividend payment made by Sun to Parrot during the current period.

Consolidation Entry E:

Excess amortization expenses relating to acquisition-date fair-value adjustments are individually recorded for the current period.

Before progressing to the final worksheet entry, note the close similarity of these entries with the five incorporated in the 2009 consolidation (Exhibit 3.5). Except for the numerical changes created by the passage of time, the entries are identical.

Consolidation Entry P:

This last entry (labeled “Entry P” because it eliminates an intercompany Payable) introduces a new element to the consolidation process. Intercompany debt transactions do not relate to outside parties. Therefore, Sun’s $40,000 payable and Parrot’s $40,000 receivable are reciprocals that must be removed on the worksheet because the companies are being reported as a single entity.

In reviewing Exhibit 3.7, note several aspects of the consolidation process:

i. The stockholders’ equity accounts of the subsidiary are removed.

ii. The Investment in Sun Company and the Equity in Subsidiary Earnings are both removed.

iii. The parent’s Retained Earnings balance is not adjusted. Because the parent applies the equity method this account should be correct.

iv. The acquisition-date fair-value adjustments to the subsidiary’s assets are recognized but only after adjustment for annual excess amortization expenses.

v. Intercompany transactions such as dividend payments and the receivable/payable are offset.

4. Subsequent Consolidation Investment Recorded Using Initial Value or Partial Equality Method:

Acquisition Made during the Current Year:

The parents company may opt to use the initial value method or the partial equity method for internal record-keeping rather than the equity method. Application of either alternative changes the balances recorded by the parent over time and, thus, the procedures followed in creating consolidations. However, choosing one of these other approaches does not affect any of the final consolidated figures to be reported.

When a company utilizes the equity method, it eliminates all reciprocal accounts, assigns unamortized fair-value allocations to specific accounts, and records amortization expense for the current year. Application of either the initial value method or the partial equity method has no effect on this basic process. For this reason, a number of the consolidation entries remain the same regardless of the parent’s investment accounting method.

In reality, just three of the parent’s accounts actually vary because of the method applied:

i. The investment account.

ii. The income recognized from the subsidiary.

iii. The parent’s retained earnings (in periods after the initial year of the combination).

Only the differences found in these balances affect the consolidation process when another method is applied. Thus, any time after the acquisition date, accounting for these three balances is of special importance.

To illustrate the modifications required by the adoption of an alternative accounting method, the consolidation of Parrot and Sun as of December 31, 2009, is reconstructed. Only one differing factor is introduced the method by which Parrot accounts for its investment. Exhibit 3.9 presents the 2009 consolidation based on Parrot’s use of the initial value method.

Exhibit 3.10 demonstrates this same process assuming that the parent applied the partial equity method. Each entry on these worksheets is labeled to correspond with the 2009 consolidation in which the parent used the equity method (Exhibit 3.5). Furthermore, differences with the equity method (both on the parent company records and with the consolidation entries) are highlighted on each of the worksheets.

Initial Value Method Applied—2009 Consolidation:

Although the initial value method theoretically stands in marked contrast to the equity method, few reporting differences actually exist. In the year of acquisition, Parrot’s income and investment accounts relating to the subsidiary are the only accounts affected.

Under the initial value method, income recognition in 2009 is limited to the $40,000 dividend received by the parent; no equity income accrual is made. At the same time, the investment account retains its $800,000 initial value. Unlike the equity method, no adjustments are recorded in the parent’s investment account in connection with the current year operations, subsidiary dividends, or amortization of any fair-value allocations.

After the composition of these two accounts has been established, worksheet entries can be used to produce the consolidated figures found in Exhibit 3.9 as of December 31. 2009.

Consolidation Entry S:

As with the previous Entry S in Exhibit 3.5, the $600,000 component of the investment account is eliminated against the beginning stockholders’ equity account of the subsidiary. Both are equivalent to Sun’s net assets at January 1, 2009, and are, therefore, reciprocal balances that must be offset. This entry is not affected by the accounting method in use.

Consolidation Entry A:

Sun’s $200,000 excess acquisition-date fair value over book value is allocated to Sun’s assets and liabilities based on their fair values at the date of acquisition. The $80,000 residual is attributed to goodwill. This procedure is identical to the corresponding entry in Exhibit 3.5 in which the equity method was applied.

Consolidation Entry I:

Under the initial value method, the parent records dividend collections as income. Entry I removes this Dividend Income account along with Sun’s Dividends Paid. From a consolidated perspective, these two $40,000 balances represent an intercompany transfer of cash that had no financial impact outside of the entity. In contrast to the equity method, Parrot has not accrued subsidiary income, nor has amortization been recorded; thus, no further income elimination is needed.

Consolidation Entry D:

When the initial value method is applied, the parent records intercompany dividends as income. Because these distributions were already removed from the consolidated totals by Entry I, no separate Entry D is required.

Consolidation Entry E:

Regardless of the parent’s method of accounting, the reporting entity must recognize excess amortizations for the current year in connection with the original fair value allocations. Thus, Entry E serves to bring the current year expenses into the consolidated financial statements.

Consequently, using the initial value method rather than the equity method changes only Entries I and D in the year of acquisition. Despite the change in methods, reported figures are still derived by- (1) eliminating all reciprocals, (2) allocating the excess portion of the acquisition- date fair values, and (3) recording amortizations on these allocations.

As indicated previously, the consolidated totals appearing in Exhibit 3.9 are identical to the figures produced previously in Exhibit 3.5. Although the income and the investment accounts on the parent company’s separate statements vary, the consolidated balances are not affected.

One significant difference between the initial value method and equity method does exist: The parent’s separate statements do not reflect consolidated income totals when the initial value method is used. Because equity adjustments (such as excess amortizations) are ignored, neither Parrot’s reported net income of $640,000 nor its retained earnings of $1,360,000 provides an accurate portrayal of consolidated figures.

Partial Equity Method Applied—2009 Consolidation:

Exhibit 3.10 presents a worksheet to consolidate these two companies for 2009 (the year of acquisition) based on the assumption that Parrot applied the partial equity method. Again, the only changes from previous examples are found in- (1) the parent’s separate records for this investment and its related income and (2) worksheet Entries I and D.

Under the partial equity approach, the parent’s record-keeping is limited to two periodic journal entries- the annual accrual of subsidiary income and the receipt of dividends. Hence, within the parent’s records, only a few differences exist when the partial equity method is applied rather than the initial value method. The entries recorded by Parrot in connection with Sun’s 2009 operations illustrate both of these approaches.

Therefore, by applying the partial equity method, the investment account on the parent’s balance sheet rises to $860,000 by the end of 2009. This total is composed of the original $800,000 acquisition-date fair value for Sun adjusted for the $100,000 income recognition and the $40,000 cash dividend payment. The same $100,000 equity income figure appears within the parent’s income statement. These two balances are appropriately found in Parrot’s records in Exhibit 3.10.

Because of the handling of income recognition and dividend payments, Entries I and D again differ on the worksheet. For the partial equity method, the $ 100,000 equity income is eliminated (Entry I) by reversing the parent’s entry. Removing this accrual allows the individual revenue and expense accounts of the subsidiary to be reported without double-counting.

The $40,000 intercompany dividend payment must also be removed (Entry D). The Dividend Paid account is simply deleted. However, elimination of the dividend from the Investment in Sun Company actually causes an increase because receipt was recorded by Parrot as a reduction in that account. All other consolidation entries (Entries S, A, and E) are the same for all three methods.

Consolidation Subsequent to Year of Acquisition—Initial Value and Partial Equity Methods:

By again incorporating the December 31, 2012, financial data for Parrot and Sun (presented in Exhibit 3.7), consolidation procedures for the initial value method and the partial equity method are examined for years subsequent to the date of acquisition. In both cases, establishment of an appropriate beginning retained earnings figure becomes a significant goal of the consolidation.

Conversion of the Parent’s Retained Earnings to a Full-Accrual (Equity) Basis:

Consolidated financial statements require a full accrual-based measurement of both income and retained earnings. The initial value method however, employs the cash basis for income recognition. The partial equity method only partially accrues subsidiary income. Thus, neither provides a full-accrual-based measure of the subsidiary activities on the parent’s income.

As a result, over time the parent’s retained earnings account fails to show a full accrual-based amount. Therefore, new worksheet adjustments are required to convert the parent’s beginning of the year retained earnings balance to a full-accrual basis. These adjustments are made to beginning of the year retained earnings because current year earnings are readily converted to full-accrual basis by simply combining current year revenue and expenses.

The resulting current year combined income figure is then added to the adjusted beginning of the year retained earnings to arrive at a full accrual ending retained earnings balance.

This concern was not faced previously when the equity method was adopted. Under that approach, the parent’s Retained Earnings account balance already reflects a full-accrual basis so that no adjustment is necessary. The $330,000 income accrual for the 2009-2011 period as well as the $21,000 amortization expense were recognized by the parent in applying the equity method.

Having been recorded in this manner, these two balances form a permanent part of Parrot’s retained earnings and are included automatically in the consolidated total. Consequently, if the equity method is applied, the process is simplified; no worksheet entries are needed to adjust the parent’s Retained Earnings account to record subsidiary operations or amortization for past years.

Conversely, if a method other than the equity method is used a worksheet change must be made to the parent’s beginning Retained Earnings account (in every subsequent year) to equate this balance with a full-accrual amount. To quantify this adjustment, the parent’s recognized income for these past three years under each method is first determined (Exhibit 3.11). For consolidation purposes, the beginning retained earnings account must then be increased or decreased to create the same effect as the equity method.

Initial Value Method Applied—Subsequent Consolidation:

As shown in Exhibit 3.11, if Parrot applied the initial value method during the 2009-2011 period it recognizes $199,000 less income than under the equity method ($309,000 – $110,000). Two items cause this difference. First, Parrot has not accrued the $220,000 increase in the subsidiary’s book value across the periods prior to the current year.

Although the $110,000 in dividends was recorded as income, the parent never recognized the remainder of the $330,000 earned by the subsidiary. Second, no accounting has been made of the $21,000 excess amortization expenses. Thus, the parent’s beginning Retained Earnings account is $199,000 ($220,000 – $21,000) below the appropriate consolidated total and must be adjusted.

To simulate the equity method so that the parent’s beginning Retained Earnings account reflects a full-accrual basis, this $199,000 increase is recorded through a worksheet entry. The initial value method figures reported by the parent effectively are converted into equity method balances.

This adjustment is labeled Entry C. The C refers to the conversion being made to equity method (full accrual) totals. The asterisk indicates that this equity simulation relates solely to transactions of prior periods. Thus, Entry C should be recorded before the other worksheet entries to align the beginning balances for the year.

Exhibit 3.12 provides a complete presentation of the consolidation of Parrot and Sun as of December 31, 2012, based on the parent’s application of the initial value method. After Entry C has been recorded on the worksheet, the remainder of this consolidation follows the same pattern as previous examples.

Sun’s stockholders’ equity accounts are eliminated (Entry S) while the allocations stemming from the $800,000 initial fair value are recorded (Entry A) at their unamortized balances as of January 1, 2012 (see Exhibit 3.8). Intercompany dividend income is removed (Entry I) and current year excess amortization expenses are recognized (Entry E). To complete this process, the intercompany debt of $40,000 is offset (Entry P).

In retrospect, the only new element introduced here is the adjustment of the parent’s beginning Retained Earnings. For a consolidation produced after the initial year of acquisition, an Entry C is required if the parent has not applied the equity method.

Partial Equity Method Applied—Subsequent Consolidation:

Exhibit 3.13 demonstrates the worksheet consolidation of Parrot and Sun as of December 31, 2012, when the investment accounts have been recorded by the parent using the partial equity method. This approach accrues subsidiary income each year but records no other equity adjustments.

Therefore, as of December 31, 2012, Parrot’s Investment in Sun Company account has a balance of $1,110,000:

As indicated here and in Exhibit 3.11, Parrot has properly recognized the yearly equity income accrual but not amortization. Consequently, if the partial equity method is in use, the parent’s beginning Retained Earnings Account must be adjusted to include this expense. The $21,000 amortization is recorded through Entry C to simulate the equity method and, hence, consolidated totals.

By recording Entry C on the worksheet, all of the subsidiary’s operational results for the 2009-2011 period are included in the consolidation. As shown in Exhibit 3.13, the remainder of the worksheet entries follow the same basic pattern as that illustrated previously for the year of acquisition (Exhibit 3.10).

Summary of Investment Methods:

Having three investment methods available to the parent means that three sets of entries must be understood to arrive at reported figures appropriate for a business combination. The process can initially seem to be a confusing overlap of procedures. However, at this point in the coverage, only three worksheet entries actually are affected by the choice of either the equity method, partial equity method, or initial value method- Entries C, I, and D.

Furthermore, accountants should never get so involved with a worksheet and its entries that they lose sight of the balances that this process is designed to calculate. These figures are never affected by the parent’s choice of an accounting method.

After the appropriate balance for each account is understood, worksheet entries assist the account in deriving these figure. To help clarify the consolidation process required under each of the three accounting methods, Exhibit 3.14 describes the purpose of each worksheet entry first during the year of acquisition and second for any period following the year of acquisition.

5. Contingent Consideration

:

Contingency agreements frequently accompany business combinations. In fact, Mergers & Acquisitions recently reported 154 deals totaling $13.9 billion of which $4.3 billion was in the form of a contingency. In many cases, the target firm asks for consideration based on projections of its future performance. The acquiring firm, however, may not share the projections and, thus, may be unwilling to pay now for uncertain future performance.

To close the deal, agreements for the acquirer’s future payments to the former owners of the target are common. Alternatively, when the acquirer’s stock comprises the consideration transferred, the sellers of the target firm may request a guaranteed minimum market value of the stock for a period of time to ensure a fair price.

SFAS 141R—Accounting for Contingent Consideration in Business Combinations:

Under the acquisition method contingent consideration obligations are recognized as part of the initial value assigned in a business combination, consistent with the fair-value concept. Therefore, the acquiring firm must estimate the fair value of the contingent portion of the total business fair value. The contingency’s fair value is recognized as part of the acquisition regardless of whether it is based on future performance of the target firm or the future stock prices of the acquirer.

As an illustration, assume that Skeptical, Inc., acquires 100 percent of the voting stock of Rosy Pictures Company on January 1, 2009, for the following consideration:

i. $550,000 market value of 10,000 shares of its $5-par common stock.

ii. A contingent payment of $80,000 cash if Rosy Pictures generates cash flows from operations of $20,000 or more in 2009.

iii. A payment of sufficient shares of Skeptical common stock to ensure a total value of $550,000 if the price per share is less than $55 on January 1, 2010.

Under the acquisition method, each of the three elements of consideration represents a portion of the negotiated fair value of Rosy Pictures and therefore must be included in the recorded value entered on Skeptical’s accounting records. For the cash contingency, Skeptical estimates that there is a 30 percent chance that the $80,000 payment will be required.

For the stock contingency, Skeptical estimates that there is a 20 percent probability that the 10,000 shares issued will have a market value of $540,000 on January 1, 2010, and an 80 percent probability that the market value of the 10,000 shares will exceed $550,000. Skeptical uses an interest rate of 4 percent to incorporate the time value of money.

To determine the fair values of the contingent consideration, Skeptical computes the present value of the expected payments as follows:

i. Cash contingency = $80,000 × 30% × (1/[1 + .04]) = $23,077

ii. Stock contingency = $10,000 × 20% × (1/[1 + .04]) = $1,923

Skeptical then records in its accounting records the acquisition of Rosy Pictures as follows:

Skeptical will report the contingent cash payment under its liabilities and the contingent stock payment as a component of stockholders’ equity. Subsequent to acquisition, obligations for contingent consideration that meet the definition of a liability will continue to be measured at fair value with adjustments recognized in income. Those obligations classified as equity are not subsequently remeasured at fair value.

To continue the preceding example, assume that in 2009 Rosy Pictures exceeds the cash flow from operations threshold of $20,000, thus requiring an additional payment of $80,000. Also, Skeptical’s stock price had fallen to $54.45 at January 1, 2010, thus requiring Skeptical to issue another 101 shares of its $5 par common stock to the former owners of Rosy Pictures.

The loss from revaluation of the contingent performance obligation is reported in Skeptical’s consolidated income statement as a component of ordinary income. Regarding the additional required stock issue, note that Skeptical’s total paid-in capital remains unchanged from the total $551,923 recorded at the acquisition date.

6. Push-Down Accounting

:

In the analysis of business combinations to this point, discussion has focused on- (1) the recording by the parent company and (2) required consolidation procedures. Unfortunately, official accounting pronouncements give virtually no guidance as to the impact of an acquisition on the separate financial statements of the subsidiary.

This issue has become especially significant in recent years because of a rash of management- led buyouts as well as corporate reorganizations. An organization, for example, might acquire a company and subsequently offer the shares back to the public in hopes of making a large profit. What should be reported in the subsidiary’s financial statements being distributed with this offering? Such deals have reheated a long-standing debate over the merits of push-down accounting, the direct recording of fair-value allocations and subsequent amortization by a subsidiary.

For this reason, the FASB has explored various methods of reporting by a company that has been acquired or reorganized. To illustrate, assume that Yarrow Company owns one asset: a building with a book value of $200,000 but a fair value of $900,000. Mannen Corporation pays exactly $900,000 in cash to acquire Yarrow. Consolidation offers no real problem here: The building will be reported by the business combination at $900,000.

However, if Yarrow continues to issue separate financial statements (for example, to its creditors or potential stockholders), should the building be reported at $200,000 or $900,000? If adjusted should the $700,000 increase be reported as a gain by the subsidiary or as an addition to contributed capital? Should depreciation be based on $200,000 or $900,000? If the subsidiary is to be viewed as a new entity with a new basis for its assets and liabilities, should Retained Earnings be returned to zero? If the parent acquires only 51 percent of Yarrow, does that change the answers to the previous questions? These questions represent just a few of the difficult issues currently being explored.

Proponents of push-down accounting argue that a change in ownership creates a new basis for subsidiary assets and liabilities. An unadjusted balance ($200,000 in the preceding illustration) is a cost figure applicable to previous stockholders. That total is no longer relevant information.

Rather, according to this argument, it is the historical cost paid by the current owner that is important, a figure that is best reflected by the expenditure made in acquiring the subsidiary. Balance sheet accounts should be reported at the cost incurred by the present stockholders ($900,000 in the illustration) rather than the cost incurred by the company. Currently, primary guidance concerning push-down accounting for external reporting purposes is provided by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Thus, the SEC requires the use of push-down accounting for the separate financial statements of any subsidiary when no substantial outside ownership of the company’s common stock, preferred stock, and publicly held debt exists. Apparently, the SEC believes that a change in ownership of that degree justifies a new basis of reporting for the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities. Until the FASB takes action, though, application is required only when the subsidiary desires to issue securities (stock or debt) to the public as regulated by the SEC.

Although the use of push-down accounting for external reporting is limited, this approach has gained significant popularity in recent years for internal reporting purposes.

Push-down accounting has several advantages for internal reporting. For example, it simplifies the consolidation process. Because the allocations and amortization have already been entered into the records of the subsidiary, worksheet Entries A (to recognize the allocations originating from the fair-value adjustments) and E (amortization expense) are not needed. Therefore, except for eliminating the effects of intercompany transactions, the assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses of the subsidiary can be added directly to those of the parent to derive consolidated totals.

More important, push-down accounting provides better information for internal evaluation. Because the subsidiary’s separate figures include amortization expense, the net income reported by the company is a good representation of the impact that the acquisition has on the earnings of the business combination.

As an example, assume that Ace Corporation owns 100 percent of Waxworth, Inc. Waxworth uses push-down accounting and reports net income of $500,000: $600,000 from operations less $100,000 in amortization expense resulting from fair-value allocations. Thus, Ace Corporation’s officials know that this acquisition has added $500,000 to the consolidated net income of the business combination. They can then evaluate whether these earnings provide a sufficient return for the parent’s investment.

However, the recording of amortization expense by the subsidiary can lead to dissension. Members of the subsidiary’s management could argue that they are being forced to record a large expense over which they have no control or responsibility. This amortization comes directly from the consideration paid by the parent but is not a result of any action taken by the subsidiary. Chesapeake Corporation has considered this problem and resolved it in the following manner- “For internal reporting of income statement activity, earnings from operations are identified separately from amortization. This allows management to analyze the subsidiary’s results without the effect of amortization.”