Compilation of advanced accounting exam questions and answers for commerce students.

Q.1. Explain the Procedures to Consolidate Variable Interest Entities.

Ans. As Power Finance’s balance sheet exemplifies, VIEs typically possess few assets and liabilities. Also, their business activities usually are strictly limited. Thus, the actual procedures to consolidate VIEs are relatively uncomplicated.

Just as in business combinations accomplished through voting interests, the financial reporting principles for consolidating variable interest entities require asset, liability, and non-controlling interest valuations. These valuations initially, and with few exceptions, are based on fair values.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Recall that SFAS 141R requires an allocation of the business fair value of an acquisition based on the underlying fair values of its assets and liabilities. In determining the total amount to consolidate for a variable interest entity, the total business fair value of the entity is the sum of-

i. Consideration transferred by the primary beneficiary.

ii. The fair value of the non-controlling interest.

The fair value principle applies to consolidating VIEs in the same manner as business combinations accomplished through voting interests. If the total business fair value of the VIE exceeds the collective fair values of its net assets, goodwill is recognized. Conversely, if the collective fair values of the net assets exceed the total business fair value, then the primary beneficiary recognizes a gain on bargain purchase.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the previous example, assuming that the debt and non-controlling interests are stated at fair values, Twin Peaks simply includes in its consolidated balance sheet the Electric Generating Plant at $400 million, the Long-Term Debt at $384 million, and a non-controlling interest of $16 million.

As a further example, General Electric Company now consolidates Penske Truck Leasing Company as a VIE under the provisions of FIN 46R. In its 2004 annual report, GE recognized an additional $1,055 billion in goodwill and more than $9 billion in property, plant, and equipment from the Penske consolidation. Prior to 2004, General Electric’s investment in Penske was accounted for under the equity method.

To illustrate the initial measurement issues that a primary beneficiary faces, assume that Vax Company invests $5 million in TLH Property, a variable interest business entity. In agreements completed July 1, 2009, Vax establishes itself as the primary beneficiary of TLH Property.

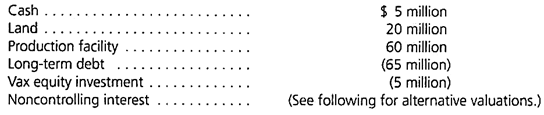

Previously, Vax had no interest in TLH. After Vax’s investment, TLH presents the following financial information at assessed fair values:

Vax will initially include each of TLH Property’s assets and liabilities at their individual fair values in its acquisition-date consolidated financial reports. According to SFAS 141R any excess of TLH Property’s acquisition-date business fair value over the collective fair values assigned to the acquired net assets must be recognized as goodwill.

Conversely, if the collective fair values of the acquired net assets exceed the VIE’s business fair value, a “gain on bargain purchase” is credited for the difference. To demonstrate these valuation principles, we use three brief examples, each with a different business fair value depending on alternative assessed fair values of the non-controlling interest.

Total Business Fair Value of VIE Equals Assessed Net Asset Value:

In this case, assume that the non-controlling interest fair value equals $15 million. The VIE’s total fair value is then $20 million ($5 million consideration paid + $15 million for the non-controlling interest). Because the total fair value is identical to the $20 million collective amount of the individually assessed fair values for the net assets ($85 million total assets — $65 million long-term debt), neither goodwill nor a gain on bargain purchase is recognized. Vax simply consolidates all assets and liabilities at their respective fair values.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Total Business Fair Value of VIE is Less Than Assessed Net Asset Value:

Alternatively, assume that the value of the non-controlling interest was assessed at only $11 million. In this case, TLH Property’s total fair value would be calculated at $16 million ($5 million consideration paid + $11 million for the non-controlling interest). The $16 million total fair value compared to the $20 million assessed fair value of TLH Property’s net assets (including cash) produces an excess of $4 million.

In essence, the business combination receives a collective $20 million net identifiable asset fair value in exchange for $16 million. In this case, Vax recognizes a gain on bargain purchase for $4 million in its current year consolidated income statement, consistent with the provisions of SFAS 141R.

Total Business Fair Value of VIE is Greater Than Assessed Net Asset Value Finally, assume that the value of the non-controlling interest is assessed at $20 million. In this case, the total fair value of TLH Property would be calculated at $25 million ($5 million consideration paid + $20 million for the non-controlling interest). The $25 million total fair value compared to the $20 million assessed fair value of TLH Property’s net assets produces an excess total fair value of $5 million. According to FIN 46R, because TLH is a business entity, Vax Company reports the excess $5 million as goodwill in its consolidated statement of financial position.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Consolidation of VIEs Subsequent to Initial Measurement:

After the initial measurement, consolidations of VIEs with their primary beneficiaries should follow the same process as if the entity were consolidated based on voting interests. Importantly, all intercompany transactions between the primary beneficiary and the VIE (including fees, expenses, other sources of income or loss, and intercompany inventory purchases) must be eliminated in consolidation. Finally, the VIE’s income must be allocated among the parties involved (i.e., equity holders and the primary beneficiary).

For a VIE, contractual arrangements, as opposed to ownership percentages, typically specify the distribution of its income. Therefore, a close examination of these contractual arrangements is needed to determine the appropriate allocation of VIE income to its equity owners and those holding variable interests.

Other FIN 46R Disclosure Requirements:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In addition to consolidated financial statements, primary beneficiaries of VIEs must also provide the following in footnotes to the financial statements:

i. The VIE’s nature, purpose, size, and activities.

ii. The carrying amount and classification of consolidated assets that are collateral for the VIE’s obligations.

iii. Lack of recourse if creditors (or beneficial interest holders) of a consolidated VIE have no recourse to the primary beneficiary’s general credit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Enterprises that hold a significant variable interest in a VIE but are not the primary beneficiary must disclose the following in footnotes to the financial statements:

i. The nature of the involvement with the VIE and when that involvement began.

ii. The nature, purpose, size, and activities of the VIE.

iii. The enterprise’s maximum exposure to loss as a result of its involvement with the VIE.

Clearly, the FASB wishes to enhance disclosures for all VIEs. Because in the past VIEs were often created in part to keep debt off a sponsoring firm’s balance sheet, these enhanced disclosures are a significant improvement in financial reporting transparency.

Q.2. How are Earnings per Share Computed for Business Combination?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ans. Consolidated Earnings Per Share:

The consolidation process affects one other intermediate accounting topic, the computation of earnings per share (EPS). As Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 128, “Earnings per Share,” requires, publicly held companies must disclose EPS each period.

The following steps calculate such figures:

i. Determine basic EPS by dividing net income (after reduction for preferred stock dividends) by the weighted average number of common stock shares outstanding for the period. If the reporting entity has no dilutive options, warrants, or other convertible items, only basic EPS is presented on the face of the income statement. However, diluted EPS also must be presented if any dilutive convertibles are present.

ii. Compute diluted EPS by combining the effects of any dilutive securities with basic earnings per share. Stock options, stock warrants, convertible debt, and convertible preferred stock often qualify as dilutive securities.

In most instances, the computation of EPS for a business combination follows the same general pattern. Consolidated net income along with the number of outstanding parent shares provides the basis for calculating basic EPS. Any convertibles, warrants, or options for the parent’s stock that can possibly dilute the reported figure must be included as described earlier in determining diluted EPS.

However, a problem arises if warrants, options, or convertibles that can dilute the subsidiary’s earnings are outstanding. Although the parent company is not directly affected the potential impact of these items on consolidated net income must be given weight in computing diluted EPS for the business combination as a whole.

Because of possible conversion, the subsidiary earnings figure included in consolidated net income is not necessarily applicable to the diluted EPS computation. Thus, the accountant must separately determine the amount of subsidiary income that should be used in deriving diluted EPS for the business combination.

Finally, in the presence of a non-controlling interest, SFAS 160 amends SFAS 128 by requiring a focus on earnings per share for the parent company stockholders.

Thus, consolidated income attributable to the parent’s interest forms the basis for the numerator in all EPS calculations for consolidated financial reporting.

Earnings Per Share Illustration:

Assume that Big Corporation has 100,000 shares of its common stock outstanding during the current year. The company also has issued 20,000 shares of nonvoting preferred stock, paying an annual cumulative dividend of $5 per share ($100,000 total). Each of these preferred shares is convertible into two shares of Big’s common stock.

Assume also that Big owns 90 percent of Little’s common stock and 60 percent of its preferred stock (which pays $12,000 in dividends per year). Annual amortization is $26,000 attributable to various intangibles. EPS computations currently are being made for 2009. During the year, Big reported separate income of $600,000 and little earned $100,000.

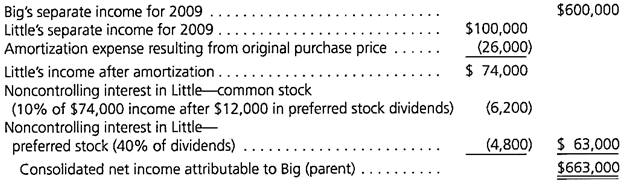

A simplified consolidation of the figures for the year indicates net income for the business combination of $663,000:

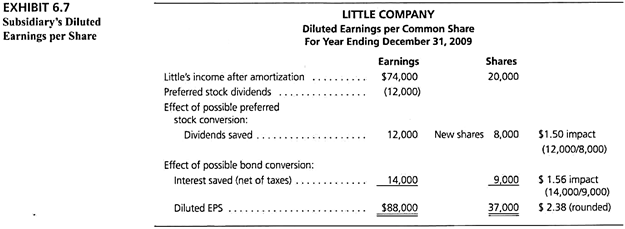

Little has 20,000 shares of common stock and 4,000 shares of preferred stock outstanding. The preferred shares pay a $3 per year dividend, and each can be converted into two shares of common stock (or 8,000 shares in total). Because Big owns only 60 percent of Little’s preferred stock, a $4,800 dividend is distributed each year to the outside owners (40 percent of $12,000 total payment).

Assume finally that the subsidiary also has $200,000 in convertible bonds outstanding that were originally issued at face value. This debt has a cash and an effective interest rate of 10 percent ($20,000 per year) and can be converted by the owners into 9,000 shares of Little’s common stock. Big owns none of these bonds. Little’s tax rate is 30 percent.

To better visualize these factors, the convertible items are scheduled as follows:

Because the subsidiary has convertible items that can affect the company’s outstanding shares and net income, Little’s diluted earnings per share must be derived before consolidated diluted EPS can be determined. As shown in Exhibit 6.7, Little’s diluted EPS are $2.38.

Two aspects of this schedule should be noted:

i. The individual impact of the convertibles ($1.50 for the preferred stock and $1.56 for the bonds) did not raise the EPS figures. Thus, neither the preferred stock nor the bonds are antidilutive, and both are properly included in these computations.

ii. Determining diluted EPS of the subsidiary is necessary only because of the possible dilutive impact. Without the subsidiary’s convertible bonds and preferred stock, consolidated net income would form the basis for computing EPS for the business combination, and only basic EPS would be reported.

According to Exhibit 6.7, Little’s income is $88,000 for diluted EPS. The issue for the accountant is how much of this amount should be included in computing consolidated diluted EPS. This allocation is based on the percentage of shares controlled by the parent. Note that if the subsidiary’s preferred stock and bonds are converted into common shares, Big’s ownership falls from 90 to 62 percent. For diluted EPS, 37,000 shares are appropriate. Big’s 62 percent ownership (22,800/37,000) is the basis for allocating the subsidiary’s $88,000 income to the parent.

We can now determine consolidated EPS. Only $54,560 of subsidiary income is appropriate for the diluted EPS computation. Because two different income figures are utilized basic and diluted calculations are made separately as in Exhibit 6.8. Consequently, these schedules determine that this business combination should report basic EPS of $5.63, with diluted earnings per share of $4.68.

Q.3. What Impact does a Subsidiary Preferred Stock have on Consolidation Process?

Ans. Although both small and large corporations routinely issue preferred shares, their presence within a subsidiary’s equity structure adds a new dimension to the consolidation process. What accounting should be made of a subsidiary’s preferred stock and the parent’s payments that are made to acquire these shares?

Recall that preferred shares, although typically nonvoting, possess other “preferences” over common shares such as a cumulative dividend preference or participation rights. Preferred shares may even offer limited voting rights. Nonetheless, preferred shares are considered as a part of the subsidiary’s stockholders’ equity and their treatment in the parent’s consolidated financial reports closely follows that for common shares.

The existence of subsidiary preferred shares does little to complicate the consolidation process. The acquisition method values all business acquisitions (whether 100 percent or less than 100 percent acquired) at their full fair values. In accounting for the acquisition of a subsidiary with preferred stock, the essential process of determining the acquisition-date business fair value of the subsidiary remains intact.

Any preferred shares not owned by the parent simply become a component of the non-controlling interest and are included in the subsidiary business fair-value calculation. The acquisition-date fair values for any subsidiary common and/or preferred shares owned by outsiders becomes the basis for the non-controlling interest valuation in the parent’s consolidated financial reports.

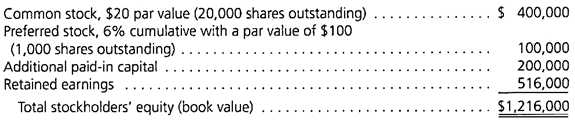

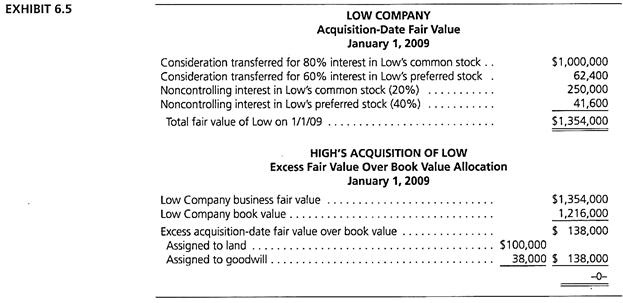

To illustrate, assume that on January 1, 2009, High Company acquires control over Low Company by purchasing 80 percent of its outstanding common stock and 60 percent of its nonvoting, cumulative, preferred stock. Low owns land undervalued in its records by $100,000, but all other assets and liabilities have fair values equal to their book values. High paid a purchase price of $1 million for the common shares and $62,400 for the preferred.

On the acquisition date, the 20 percent non-controlling interest in the common shares had a fair value of $250,000 and the 40 percent preferred stock non-controlling interest had a fair value of $41,600.

Low’s capital structure immediately prior to the acquisition is shown below:

Exhibit 6.5 shows High’s calculation of the acquisition-date fair value of Low and the allocation of the difference between the fair and book values to land and goodwill.

As seen in Exhibit 6.5, the subsidiary’s ownership structure (i.e., comprising of both preferred and common shares) does not affect the fair-value principle for determining the basis for consolidating the subsidiary. Moreover, the acquisition method follows the same procedure for calculating business fair value regardless of the various preferences the preferred shares may possess.

Any cumulative or participating preferences (or any additional rights) attributed to the preferred shares are assumed to be captured by the acquisition-date fair value of the shares and thus automatically incorporated into the subsidiary’s valuation basis for consolidation.

By utilizing the information above, we next construct a basic worksheet entry as of January 1, 2009 (the acquisition date). In the presence of both common and preferred subsidiary shares, combining the customary consolidation entries S and A avoids an unnecessary allocation of the subsidiary’s retained earnings across these equity shares. The combined consolidation entry also recognizes the allocations made to the undervalued land and goodwill. No other consolidation entries are needed because no time has passed since the acquisition took place.

The above combined consolidation entry recognizes the non-controlling interest as the total of acquisition-date fair values of $250,000 for the common stock and $41,600 for the preferred shares. Consistent with previous consolidation illustrations throughout the text, the entire subsidiary’s stockholders’ equity section is eliminated along with the parent’s investment accounts—in this case for both the common and preferred shares.

Allocation of Subsidiary Income:

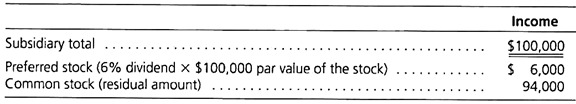

The final factor influencing a consolidation that includes subsidiary preferred shares is the allocation of the company’s income between the two types of stock. A division must be made for every period subsequent to the takeover- (1) to compute the non-controlling interest’s share and (2) for the parent’s own recognition purposes. For a cumulative, nonparticipating preferred stock such as the one presently being examined only the specified annual dividend is attributed to the preferred stock with all remaining income assigned to common stock.

Consequently, if we assume that Low reports earnings of $100,000 in 2009 while paying the annual $6,000 dividend on its preferred stock, we allocate income for consolidation purposes as follows:

During 2009, High Company, as the parent, is entitled to $3,600 in dividends from Low’s preferred stock because of its 60 percent ownership. In addition, High holds 80 percent of Low’s common stock so that another $75,200 of the income ($94,000 X 80%) is attributed to the parent.

The non-controlling interest in the subsidiary’s income can be calculated in a similar fashion:

Q.4. How to Determine Reportable Operating Segments?

Ans. After a company has identified its operating segments based on its internal reporting system, management must decide which segments to report separately. Generally, information must be reported separately for each operating segment that meets one or more quantitative thresholds established in SFAS 131.

However, if two or more operating segments have essentially the same business activities in essentially the same economic environments, information for those individual segments may be combined. “For example, a retail chain may have 10 stores that individually meet the definition of an operating segment, but each store is essentially the same as the others.” In that case, the FASB believes that the benefit to be derived from separately reporting each operating segment would not justify the cost of disclosure.

In determining whether business activities and environments are similar, management must consider these aggregation criteria:

1. The nature of the products and services provided by each operating segment.

2. The nature of the production process.

3. The type or class of customer.

4. The distribution methods.

5. If applicable, the nature of the regulatory environment.

Segments must be similar in each and every one of these areas to be combined. However, aggregation of similar segments is not required.

Quantitative Thresholds:

After determining whether any segments are to be combined, management next must decide which of its operating segments are significant enough to justify separate disclosure.

In SFAS 131, the FASB decided to retain the three tests introduced in SFAS 14 for identifying operating segments for which separate disclosure is required:

i. A revenue test.

ii. A profit or loss test.

iii. An asset test.

An operating segment needs to satisfy only one of these tests to be considered of significant size to necessitate separate disclosure.

To apply these three tests, a segment’s revenues, profit or loss, and assets must be determined. SFAS 131 does not stipulate a specific measure of profit or loss, such as operating profit or income before taxes, to be used in applying these tests. Instead, the profit measure used by the chief operating decision maker in evaluating operating segments is to be used.

An operating segment is considered to be significant if it meets any one of the following tests:

1. Revenue test- Segment revenues, both external and intersegment, are 10 percent or more of the combined revenue, internal and external, of all reported operating segments.

2. Profit or loss test- Segment profit or loss is 10 percent or more of the higher (in absolute terms) of the combined reported profit of all profitable segments or the combined reported loss of all segments incurring a loss.

3. Asset test- Segment assets are 10 percent or more of the combined assets of all operating segments.

Application of the revenue and asset tests appears to pose few problems. In contrast, the profit or loss test is more complicated and warrants illustration.

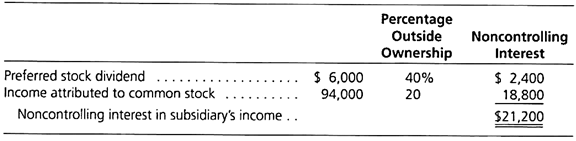

For this purpose, assume that Durham Company has five separate operating segments with the following profits or losses:

Durham Company Segments—Profits and Losses:

Three of these industry segments (soft drinks, food products, and paper packaging) report profits that total $2,820,000. The two remaining segments have losses of $730,000 for the year.

Consequently, $2,820,000 serves as the basis for the profit or loss test because that figure is higher in absolute terms than $730,000. Based on the 10 percent threshold, any operating segment with either a profit or loss of more than $282,000 (10% × $2,820,000) is considered material and, thus, must be disclosed separately. According to this one test, the soft drink and paper packaging segments (with operating profits of $1.7 million and $880,000, respectively) are both judged to be reportable as is the wine segment, despite having a loss of $600,000.

Operating segments that do not meet any of the quantitative thresholds may be combined to produce a reportable segment if they share a majority of the aggregation criteria listed earlier. Durham Company’s food products and recreation parks operating segments do not meet any of the aggregation criteria. Operating segments that are not individually significant and that cannot be aggregated with other segments are combined and disclosed in an all other category. The sources of the revenues included in the All Other category must be disclosed.

Q.5. Explain the Pooling of Interests Method of Accounting for Business Combinations.

Ans. The SFAS 141R acquisition method actually represents the third method that financial accounting standard setters have approved for business combinations. Prior to 2002, APB 16, “Business Combinations,” allowed two alternatives—the purchase method and the pooling of interests method.

Although SFAS 141 eliminated the pooling of interests method, the prohibition was prospective. Consequently, many consolidated financial statements today continue to show the effects of past pooling of interests accounting. Therefore, to fully appreciate financial reporting for business combinations, a familiarity with the pooling of interests method remains necessary.

Historically, former owners of separate firms would agree to combine for their mutual benefit and continue as owners of a combined firm. It was asserted that the assets and liabilities of the former firms were never really bought or sold; former owners merely exchanged ownership shares to become joint owners of the combined firm.

Combinations characterized by exchange of voting shares and continuation of previous ownership became known as pooling of interests. Rather than an exchange transaction with one ownership group replacing another, a pooling of interests was characterized by a continuity of ownership interests before and after the business combination. Prior to its elimination, this method was applied to a significant number of business combinations.

To reflect the continuity of ownership, two important steps characterized the pooling of interests method:

1. The book values of the assets and liabilities of both companies became the book values reported by the combined entity.

2. The revenue and expense accounts were combined retrospectively as well as prospectively. Again, continuity of ownership allowed for the recognition of income accruing to the owners both before and after the combination.

Therefore, in a pooling, reported income was typically higher than under the contemporaneous purchase accounting. Under pooling, not only did the firms retrospectively combine incomes but also the smaller asset bases resulted in smaller depreciation and amortization expenses. Because net income reported in financial statements often is used in a variety of contracts, including managerial compensation, managers considered the pooling method an attractive alternative to purchase accounting.

The APB, in Opinion 16, allowed both the purchase and pooling of interest methods to account for business combinations. However, the Board placed tight restrictions on the pooling method to prevent managers from engaging in purchase transactions and reporting them as poolings of interest. Business combinations that failed to meet the criteria had to be accounted for by the purchase method.

These criteria had two overriding objectives. First, to ensure the complete fusion of the two organizations, one company had to obtain substantially all (90 percent or more) of the voting stock of the other. The second general objective of these criteria was to prevent purchase combinations from being disguised as poolings.

Past experience had shown that combination transactions were frequently manipulated so that they would qualify for pooling of interests treatment (usually to increase reported earnings). However, subsequent events, often involving cash being paid or received by the parties, revealed the true nature of the combination: One company was purchasing the other in a bargained exchange. The APB designed a number of its criteria to stop this practice.

Pooling of Interests—Asset Valuation and Income Determination:

Because a pooling of interests was predicated on a continuity of ownership, the accounting incorporated a continuation of previous book values and ignored fair values exchanged in a business combination. To demonstrate, we again assume that Archer, Inc., acquires all of Baker Company’s assets and liabilities in a merger (see Exhibit 2.8). We assume as before that Archer, Inc., issues stock with a fair value of $1,200,000 to Baker’s former owners.

In connection with the acquisition, Archer paid $25,000 legal and accounting fees. Also, Archer agreed to pay the former owners additional consideration contingent upon the completion of Baker’s existing contracts at specified profit margins. The current fair value of the contingent obligation was estimated to be $150,000.

The following table compares the amounts from Baker that Archer would include in its acquisition-date consolidated financial statements under the pooling of interests method, the purchase method, and the acquisition method.

Several observations about the pooling of interests method and comparisons to the fair-value- based methods can be made:

i. In consolidating Baker’s assets and liabilities, the pooling method uses previous book values and ignores fair values. Consequently, although a fair value of $1,350.000 is exchanged, only a net value of $165.000 (assets less liabilities) is reported in the pooling. In contrast, the purchase and acquisition methods record fair values.

ii. Because the pooling values an acquired firm at its previously recorded book value, no new amount for goodwill is recorded. Similarly, other unrecorded intangibles (e.g., licensing agreements) remain unrecorded on the continuing firm’s books.

iii. The pooling method as reflected in the preceding example, typically shows smaller asset values and consequently lowers future depreciation and amortization expenses. Thus, higher future net income was usually reported under the pooling method compared to similar situations that employed the purchase method.

iv. Although not shown, the pooling method retrospectively combined the acquired firm’s revenues, expenses, dividends, and retained earnings. The purchase and acquisition methods incorporate only post acquisition values for these operational items. Also APB Opinion 16 required that all costs of the combination (direct and indirect acquisition costs and stock issue costs) be expensed in the period of combination under the pooling of interests method.

v. Finally, with, adoption of the acquisition method the FASB has moved clearly in the direction of increased management accountability for the fair values of all assets acquired and liabilities assumed in a business combination.