Many partnerships limit capital transactions almost exclusively to contributions, drawings, and profit and loss allocations. Normally, though, over any extended period, changes in the members who make up a partnership occur. Employees may be promoted into the partnership or new owners brought in from outside the organization to add capital or expertise to the business. Current partners eventually retire, die, or simply elect to leave the partnership. Large operations may even experience such changes on a routine basis.

Regardless of the nature or the frequency of the event, any alteration in the specific individuals composing a partnership automatically leads to legal dissolution. In many instances, the breakup is merely a prerequisite to the formation of a new partnership. For example, if Abernethy and Chapman decide to allow Miller to become a partner in their business, the legally recognized partnership of Abernethy and Chapman has to be dissolved first.

The business property as well as the right to future profits can then be conveyed to the newly formed partnership of Abernethy, Chapman, and Miller. The change is a legal one. Actual operations of the business would probably continue unimpeded by this alteration in ownership.

Conversely, should the partners so choose, dissolution can be a preliminary step in the termination and liquidation of the business. The death of a partner, lack of sufficient profits, or internal management differences can lead the partners to break up the partnership business. Under this circumstance, the partnership sells properties, pays debts, and distributes any remaining assets to the individual partners. Thus, in liquidations both the partnership and the business cease to exist.

Dissolution—Admission of a New Partner:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

One of the most prevalent changes in the makeup of a partnership is the addition of a new partner. An employee may have worked for years to gain this opportunity, or a prospective partner might offer the new investment capital or business experience necessary for future business success.

An individual can gain admittance to a partnership in one of two ways:

(1) By purchasing an ownership interest from a current partner, or

(2) By contributing assets directly to the business.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In recording either type of transaction, the accountant has the option, once again, to retain the book value of all partnership assets and liabilities (as exemplified by the bonus method) or revalue these accounts to their present fair values (the goodwill method). The decision as to a theoretical preference between the bonus and goodwill methods hinges on one single question- Should the dissolved partnership and the newly formed partnership be viewed as two separate reporting entities?

If the new partnership is merely an extension of the old, no basis exists for restatement. The transfer of ownership is a change only in a legal sense and has no direct impact on business assets and liabilities. However, if the continuation of the business represents a legitimate transfer of property from one partnership to another, revaluation of all accounts and recognition of goodwill can be justified.

Because both approaches are encountered in practice, this textbook presents each. However, the concerns in connection with partnership goodwill still exist- Recognition is not based on historical cost and no objective verification of the amount being capitalized can be made. One alternative revaluation approach that attempts to circumvent the problems involved with partnership goodwill has been devised. This hybrid method revalues all partnership assets and liabilities to fair value without making any corresponding recognition of goodwill.

Admission through Purchase of a Current Interest:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

One method of gaining admittance to a partnership is by the purchase of a current interest. One or more partners can choose to sell their portion of the business to an outside party. This type of transaction is most common in operations that rely primarily on monetary capital rather than on the business expertise of the partners.

In making a transfer of ownership, a partner can actually convey only three rights:

1. The right of co-ownership in the business property. This right justifies the partner’s periodic drawings from the business as well as the distribution settlement paid at liquidation or at the time of a partner’s withdrawal.

2. The right to share in profits and losses as specified in the articles of partnership.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. The right to participate in the management of the business.

Unless restricted by the articles of partnership, every partner has the power to sell or assign the first two of these rights at any time. Their transfer poses no threat of financial harm to the remaining partners. In contrast, partnership law states that the right to participate in the management of the business can be conveyed only with the consent of all partners.

This particular right is considered essential to the future earning power of the enterprise as well as the maintenance of business assets. Therefore, current partners are protected from the intrusion of parties who might be considered detrimental to the management of the company.

As an illustration, assume that Scott, Thompson, and York formed a partnership several years ago. Subsequently, York decides to leave the partnership and offers to sell his interest to Morgan. Although York may transfer the right of property ownership as well as the specified share of future profits and losses, the partnership does not automatically admit Morgan. York legally remains a partner until such time as both Scott and Thompson agree to allow Morgan to participate in the management of the business.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To demonstrate the accounting procedures applicable to the transfer of a partnership interest, assume that the following information is available relating to the partnership of Scott, Thompson, and York:

As often happens, the relationship of the capital accounts to one another does not correspond with the partners’ profit and loss ratio. Capital balances are historical cost figures. They result from contributions and withdrawals made throughout the life of the business as well as from the allocation of partnership income.

Therefore, any correlation between a partner’s recorded capital at a particular point in time and the profit and loss percentage would probably be coincidental. Scott, for example, has 50 percent of the current partnership capital ($50,000/$100,000) but is entitled to only a 20 percent allocation of income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Instead of York selling his interest to Morgan, assume that each of these three partners elects to transfer a 20 percent interest to Morgan for a total payment of $30,000. According to the sales contract, the money is to be paid directly to the owners.

One approach to recording this transaction is that, because Morgan’s purchase is carried out between the individual parties, the acquisition has no impact on the assets and liabilities the partnership holds. Because the business is not involved directly, the transfer of ownership requires a simple capital reclassification without any accompanying revaluation. Book value is retained. This approach is similar to the bonus method; only a legal change in ownership is occurring so that revaluation of neither assets or liabilities nor goodwill is appropriate.

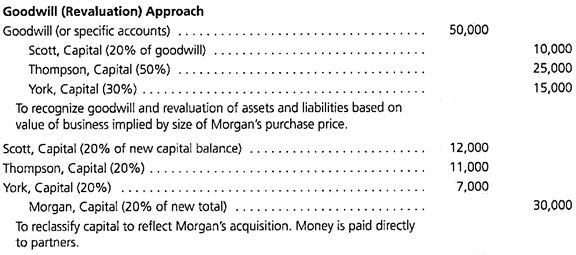

An alternative for recording Morgan’s acquisition relies on a different perspective of the new partner’s admission. Legally, the partnership of Scott, Thompson, and York is transferring all assets and liabilities to the partnership of Scott, Thompson, York, and Morgan. Therefore, according to the logic underlying the goodwill method, a transaction is occurring between two separate reporting entities, an event that necessitates the complete revaluation of all assets and liabilities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Because Morgan is paying $30,000 for a 20 percent interest in the partnership, the implied value of the business as a whole is $150,000 ($30,000/20%). However, the book value is only $100,000; thus, a $50,000 upward revaluation is indicated. This adjustment is reflected by restating specific partnership asset and liability accounts to fair value with any remaining balance being recorded as goodwill. After the implied value of the partnership is established, the reclassification of ownership can be recorded based on the new capital balances.

As this entry indicates, the $50,000 revaluation is credited to the original partners based on the profit and loss ratio rather than on their percentages of capital. Recognition of goodwill (or an increase in the book value of specific accounts) indicates that unrecorded gains have accrued to the business during the previous years of operation. Therefore, the equitable treatment is to allocate this increment among the partners according to their profit and loss percentages.

Admission by a Contribution Made to the Partnership:

Entrance into a partnership is not limited solely to the purchase of a current partner’s interest. An outsider may be admitted to the ownership by contributing cash or other assets directly to the business rather than to the partners. For example, assume that King and Wilson maintain a partnership and presently report capital balances of $80,000 and $20,000, respectively.

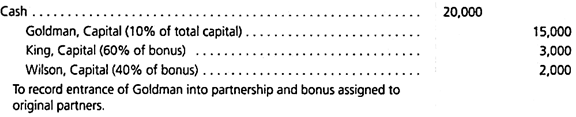

According to the articles of partnership, King is entitled to 60 percent of all profits and losses with the remaining 40 percent credited each year to Wilson. By agreement of the partners, Goldman is being allowed to enter the partnership for a payment of $20,000 with this money going into the business. Based on negotiations that preceded the acquisition, all parties have agreed that Goldman receives an initial 10 percent interest in partnership property.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Bonus Credited to Original Partners:

The bonus (or no revaluation) method maintains the same recorded value for all partnership assets and liabilities despite Goldman’s admittance. The capital balance for this new partner is simply set at the appropriate 10 percent level based on the book value of the partnership taken as a whole (after the payment is recorded). Because $20,000 is being invested, total reported capital increases to $120,000. Thus, Goldman’s 10 percent interest is computed as $12,000.

The $8,000 difference between the amount contributed and this allotted capital balance is viewed as a bonus. Because Goldman is willing to accept a capital balance that is less than the investment being made, this bonus is attributed to the original partners (again based on their profit and loss ratio). As a result of the nature of the transaction, no need exists to recognize goodwill or revalue any of the assets or liabilities.

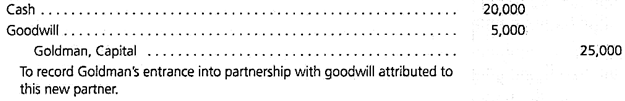

Goodwill Credited to Original Partners:

The goodwill method views Goldman’s payment as evidence that the partnership as a whole possesses an actual value of $200,000 ($20,000/10%). Because, even with the new partner’s investment, only $120,000 in net assets is being reported, a valuation adjustment of $80,000 is implied. Over the previous years, unrecorded gains have apparently accrued to the business. This $80,000 figure might reflect the need to revalue specific accounts such as inventory or equipment, although the entire amount, or some portion of it, may simply be recorded as goodwill.

Comparison of Bonus Method and Goodwill Method:

Completely different capital balances as well as asset and liability figures result from these two approaches. In both cases, however, the new partner is credited with the appropriate 10 percent of total partnership capital.

Because Goldman contributed an amount more than 10 percent of the partnership’s resulting book value, this business is perceived as being worth more than the recorded accounts indicate. Therefore, the bonus in the first instance and the goodwill in the second were both assumed as accruing to the two original partners. Such a presumption is not unusual in an established business, especially if profitable operations have developed over a number of years.

Hybrid Method of Recording Admission of New Partner:

One other approach to Goldman’s admission can be devised. Assume that the assets and liabilities of the King and Wilson partnership have a book value of $100,000 as stated earlier. Also assume that a piece of land held by the business is actually worth $30,000 more than its currently recorded book value. Thus, the identifiable assets of the partnership are worth $130,000. Goldman pays $20,000 for a 10 percent interest.

In this approach, the identifiable assets (such as land) are revalued but no goodwill is recognized.

The admission of Goldman and the payment of $20,000 bring the total capital balance to $150,000. Because Goldman is acquiring a 10 percent interest, a capital balance of $15,000 is recorded. The extra $5,000 payment ($20,000 – $15,000) is attributed as a bonus to the original partners. In this way, asset revaluation and a capital bonus are both used to align the accounts.

Bonus or Goodwill Credited to New Partner:

Goldman also may be contributing some attribute other than tangible assets to this partnership. Therefore, the articles of partnership may be written to credit the new partner, rather than the original partners, with either a bonus or goodwill. Because of an excellent professional reputation, valuable business contacts, or myriad other possible factors, Goldman might be able to negotiate a beginning capital balance in excess of the $20,000 cash contribution. This same circumstance may also result if the business is desperate for new capital and is willing to offer favorable terms as an enticement to the potential partner.

To illustrate, assume that Goldman receives a 20 percent interest in the partnership (rather than the originally stated 10 percent) in exchange for the $20,000 cash investment. The specific rationale for the higher ownership percentage need not be identified.

The bonus method sets Goldman’s initial capital at $24,000 (20 percent of the $120,000 book value). To achieve this balance, a capital bonus of $4,000 must be credited to Goldman and taken from the present partners:

If goodwill rather than a bonus is attributed to the entering partner, a mathematical problem arises in determining the implicit value of the business as a whole. In the current illustration, Goldman paid $20,000 for a 20 percent interest. Therefore, the value of the company is calculated as only $100,000 ($20,000/20%), a figure that is less than the $120,000 in net assets being reported after the new contribution.

Negative goodwill appears to exist. One possibility is that individual partnership assets are overvalued and require reduction. As an alternative, the cash contribution might not be an accurate representation of the new partner’s investment. Goldman could be bringing an intangible contribution (goodwill) to the business along with the $20,000.

This additional amount must be determined algebraically:

If the partners determine that Goldman is, indeed, making an intangible contribution (a particular skill, for example, or a loyal clientele), Goldman should be credited with a $25,000 capital investment- $20,000 cash and $5.000 goodwill. When added to the original $100,000 in net assets reported by the partnership, this contribution raises the total capital for the business to $125,000. As the articles of partnership specified Goldman’s interest now represents a 20 percent share of the partnership ($25.000/$125,000).

Recognizing $5.000 in goodwill has established the proper relationship between the new partner and the partnership.

Therefore, the following journal entry reflects this transaction:

Dissolution—Withdrawal of a Partner:

Admission of a new partner is not the only method by which a partnership can undergo a change in composition. Over the life of the business, partners might leave the organization. Death or retirement can occur, or a partner may simply elect to withdraw from the partnership. The articles of partnership also can allow for the expulsion of a partner under certain conditions. Again, any change in membership legally dissolves the partnership, although its operations usually continue uninterrupted under the remaining partners’ ownership.

Regardless of the reason for dissolution, some method of establishing an equitable settlement of the withdrawing partner’s interest in the business is necessary. Often, the partner (or the partner’s estate) may simply sell the interest to an outside party, with approval, or to one or more of the remaining partners. As an alternative, the business can distribute cash or other assets as a means of settling a partner’s right of co-ownership. Consequently, many partnerships hold life insurance policies solely to provide adequate cash to liquidate a partner’s interest upon death.

Whether death or some other reason caused the withdrawal, a final distribution will not necessarily equal the book value of the partner’s capital account. A capital balance is only a recording of historical transactions and rarely represents the true value inherent in a business. Instead payment is frequently based on the value of the partner’s interest as ascertained by either negotiation or appraisal. Because a settlement determination can be derived in many ways, the articles of partnership should contain exact provisions regulating this procedure.

The withdrawal of an individual partner and the resulting distribution of partnership property can, as before, be accounted for by either the bonus (no revaluation) method or the goodwill (revaluation) method. Again, a hybrid option is also available.

If a bonus is recorded the amount can be attributed to either of the parties involved- the withdrawing partner or the remaining partners. Conversely, any revaluation of partnership property (as well as the establishment of a goodwill balance) is allocated among all partners to recognize possible unrecorded gains. The hybrid approach restates assets and liabilities to fair value but does not record goodwill. This last alternative reflects the legal change in ownership but avoids the theoretical problems associated with partnership goodwill.

Accounting for the Withdrawal of a Partner—Illustration:

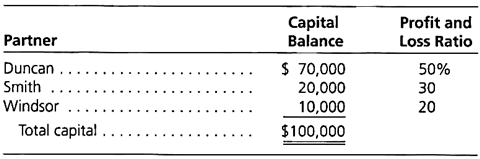

To demonstrate the various approaches that can be taken to account for a partner’s withdrawal, assume that the partnership of Duncan, Smith, and Windsor has existed for a number of years.

At the present time, the partners have the following capital balances as well as the indicated profit and loss percentages:

Windsor decides to withdraw from the partnership, but Duncan and Smith plan to continue operating the business.

As per the original partnership agreement, a final settlement distribution for any withdrawing partner is computed based on the following specified provisions:

1. An independent expert will appraise the business to determine its estimated fair value.

2. Any individual who leaves the partnership will receive cash or other assets equal to that partner’s current capital balance after including an appropriate share of any adjustment indicated by the previous valuation. The allocation of unrecorded gains and losses is based on the normal profit and loss ratio.

Following Windsor’s decision to withdraw from the partnership, its property is immediately appraised. Total fair value is estimated at $80,000, a figure $80,000 in excess of book value. According to this valuation, land held by the partnership is currently worth $50,000 more than its original cost. In addition, $30,000 in goodwill is attributed to the partnership based on its value as a going concern. Therefore, Windsor receives $26,000 on leaving the partnership- the original $10,000 capital balance plus a 20 percent share of this $80,000 increment. The amount of payment is not in dispute, but the method of recording the withdrawal is.

Bonus Method Applied:

If the partnership used the bonus method to record this transaction, the extra $16,000 paid to Windsor is simply assigned as a decrease in the remaining partners’ capital accounts. Historically, Duncan and Smith have been credited with 50 percent and 30 percent of all profits and losses, respectively.

This same relative ratio is used now to allocate the reduction between these two remaining partners on a 5/8 and 3/8 basis:

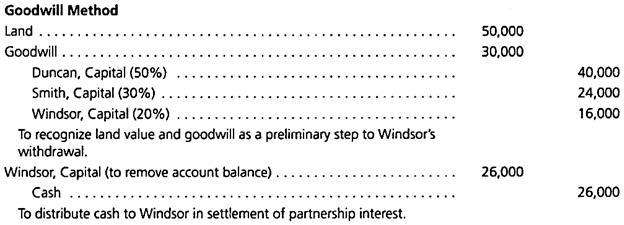

Goodwill Method Applied:

This same transaction can also be accounted for by means of the goodwill (or revaluation) approach. The appraisal indicates that land is undervalued on the partnership’s records by $50,000 and that goodwill of $30,000 has apparently accrued to the business over the years. The first of the following entries recognizes these valuations. This adjustment properly equates Windsor’s capital balance with the $26,000 cash amount to be distributed. Windsor’s equity balance is merely removed in the second entry at the time of payment.

The implied value of a partnership as a whole cannot be determined directly from the amount distributed to a withdrawing partner. For example, paying Windsor $26,000 did not indicate that total capital should be $130,000 ($26,000/20%). This computation is appropriate only when- (1) a new partner is admitted or (2) the percentage of capital is the same as the profit and loss ratio.

Here, an outside valuation of the business indicated that it was worth $80,000 more than book value. As a 20 percent owner, Windsor was entitled to $16,000 of that amount, raising the partner’s capital account from $10.000 to $26,000, the amount of the final payment.

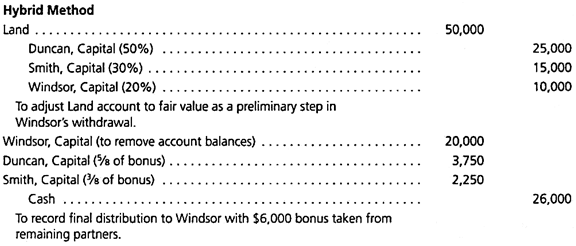

Hybrid Method Applied:

A hybrid approach also can be adopted to record a partner’s withdrawal. It also recognizes asset and liability revaluations but ignores goodwill. A bonus must then be recorded to reconcile the partner’s adjusted capital balance with the final distribution.

The following journal entry, for example, does not record goodwill. However, the book value of the land is increased by $50,000 in recognition of present worth. This adjustment increases Windsor’s capital balance to $20,000, a figure that is still less than the $26,000 distribution. The $6,000 difference is recorded as a bonus taken from the remaining two partners according to their relative profit and loss ratio.