Export sales and import purchases are international transactions; they are components of what is called trade. When two parties from different countries enter into a transaction, they must decide which of the two countries’ currencies to use to settle the transaction. For example, if a U.S. computer manufacturer sells to a customer in Japan, the parties must decide whether the transaction will be denominated (payment will be made) in U.S. dollars or Japanese yen.

Assume that a U.S. exporter (Amerco) sells goods to a German importer that will pay in euros (€). In this situation, Amerco has entered into a foreign currency transaction. It must restate the euro amount that it actually will receive into U.S. dollars to account for this transaction. This happens because Amerco keeps its books and prepares financial statements in U.S. dollars. Although the German importer has entered into an international transaction, it does not have a foreign currency transaction (payment will be made in its currency) and no restatement is necessary.

Assume that, as is customary in its industry, Amerco does not require immediate payment and allows its German customer 30 days to pay for its purchases. By doing this, Amerco runs the risk that the euro might depreciate against the U.S. dollar between the sale date and the date of payment. If so, the sale would generate fewer U.S. dollars than it would have had the euro not decreased in value, and the sale is less profitable because it was made on a credit basis. In this situation Amerco is said to have an exposure to foreign exchange risk.

Specifically, Amerco has a transaction exposure that can be summarized as follows:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. Export Sale:

A transaction exposure exists when the exporter allows the buyer to pay in a foreign currency and allows the buyer to pay sometime after the sale has been made. The exporter is exposed to the risk that the foreign currency might depreciate (decrease in value) between the date of sale and the date of payment, thereby decreasing the U.S. dollars ultimately collected.

ii. Import Purchase:

A transaction exposure exists when the importer is required to pay in foreign currency and is allowed to pay sometime after the purchase has been made. The importer is exposed to the risk that the foreign currency might appreciate (increase in price) between the date of purchase and the date of payment, thereby increasing the U.S. dollars that have to be paid for the imported goods.

Accounting Issue:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The major issue in accounting for foreign currency transactions is how to deal with the change in U.S. dollar value of the sales revenue and account receivable resulting from the export when the foreign currency changes in value. (The corollary issue is how to deal with the change in the U.S. dollar value of the account payable and goods being acquired in an import purchase.) For example, assume that Amerco, a U.S. company, sells goods to a German customer at the price of 1 million euros when the spot exchange rate is $1.32 per euro.

If payment were received at the sale date, Amerco could have converted 1 million euros into $1,320,000; this amount clearly would be the amount at which the sales revenue would be recognized. Instead, Amerco allows the German customer 30 days to pay for its purchase. At the end of 30 days, the euro has depreciated to $1.30 and Amerco is able to convert the 1 million euros received on that date into only $1,300,000. How should Amerco account for this $20,000 decrease in value?

Accounting Alternatives:

Conceptually, the two methods of accounting for changes in the value of a foreign currency transaction are the one-transaction perspective and the two-transaction perspective. The one- transaction perspective assumes that an export sale is not complete until the foreign currency receivable has been collected and converted into U.S. dollars. Any change in the U.S. dollar value of the foreign currency is accounted for as an adjustment to Accounts Receivable and to Sales.

Under this perspective, Amerco would ultimately report Sales at $1,300,000 and an increase in the Cash account of the same amount. This approach can be criticized because it hides the fact that the company could have received $1,320,000 if the German customer had been required to pay at the date of sale. Amerco incurs a $20,000 loss because of the depreciation in the euro, but that loss is buried in an adjustment to Sales. This approach is not acceptable under U.S. GAAP.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Instead, FASB Statement No. 52 requires companies to use a two-transaction perspective in accounting for foreign currency transactions. This perspective treats the export sale and the subsequent collection of cash as two separate transactions. Because management has made two decisions—(1) to make the export sale and (2) to extend credit in foreign currency to the customer—the company should report the income effect from each of these decisions separately.

The U.S. dollar value of the sale is recorded at the date the sale occurs. At that point, the sale has been completed; there are no subsequent adjustments to the Sales account. Any difference between the number of U.S. dollars that could have been received at the date of sale and the number of U.S. dollars actually received at the date of collection due to fluctuations in the exchange rate is a result of the decision to extend foreign currency credit to the customer. This difference is treated as a foreign exchange gain or loss that is reported separately from Sales in the income statement.

Using the two-transaction perspective to account for its export sale to Germany, Amerco would make the following journal entries:

Sales are reported in income at the amount that would have been received if the customer had not been given 30 days to pay the 1 million euros—that is, $1,320,000. A separate Foreign Exchange Loss of $20,000 is reported in income to indicate that because of the decision to extend foreign currency credit to the German customer and because the euro decreased in value, Amerco actually received fewer U.S. dollars.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Note that Amerco keeps its Account Receivable (€) account separate from its U.S. dollar receivables. Companies engaged in international trade need to keep separate payable and receivable accounts in each of the currencies in which they have transactions. Each foreign currency receivable and payable should have a separate account number in the company’s chart of accounts.

We can summarize the relationship between fluctuations in exchange rates and foreign exchange gains and losses as follows:

A foreign currency receivable arising from an export sale creates an asset exposure to foreign exchange risk. If the foreign currency appreciates, the foreign currency asset increases in U.S. dollar value and a foreign exchange gain arises; depreciation of the foreign currency causes a foreign exchange loss.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A foreign currency payable arising from an import purchase creates a liability exposure to foreign exchange risk. If the foreign currency appreciates, the foreign currency liability increases in U.S. dollar value and a foreign exchange loss results; depreciation of the currency results in a foreign exchange gain.

Balance Sheet Date before Date of Payment:

The question arises as to what adjustments should be made if a balance sheet date falls between the date of sale and the date of payment. For example, assume that Amerco shipped goods to its German customer on December 1, 2009, with payment to be received on March 1, 2010. Assume that at December 1, the spot rate for the euro was $1.32, but by December 31, the euro has appreciated to $1.33. Is any adjustment needed at December 31, 2009, when the books are closed to account for the fact that the foreign currency receivable has changed in U.S. dollar value since December 1?

The general consensus worldwide is that a foreign currency receivable or foreign currency payable should be revalued at the balance sheet date to account for the change in exchange rates. Under the two-transaction perspective, this means that a foreign exchange gain or loss arises at the balance sheet date. The next question then is what should be done with these foreign exchange gains and losses that have not yet been realized in cash. Should they be included in net income?

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The two approaches to accounting for unrealized foreign exchange gains and losses are the deferral approach and the accrual approach. Under the deferral approach, unrealized foreign exchange gains and losses are deferred on the balance sheet until cash is actually paid or received. When cash is paid or received, a realized foreign exchange gain or loss is included in income. This approach is not acceptable under US. GAAP.

SFAS 52 requires U.S. companies to use the accrual approach to account for unrealized foreign exchange gains and losses. Under this approach, a firm reports unrealized foreign exchange gains and losses in net income in the period in which the exchange rate changes. SFAS 52 says, “This is consistent with accrual accounting; it results in reporting the effect of a rate change that will have cash flow effects when the event causing the effect takes place.”

Thus, any change in the exchange rate from the date of sale to the balance sheet date results in a foreign exchange gain or loss to be reported in income in that period. Any change in the exchange rate from the balance sheet date to the date of payment results in a second foreign exchange gain or loss that is reported in the second accounting period.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

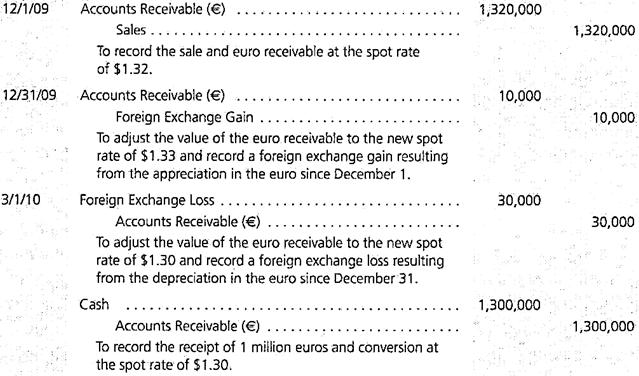

Amerco makes the following journal entries under the accrual approach:

The net impact on income in 2009 is a sale of $1,320,000 and a foreign exchange gain of $10,000; in 2010, Amerco records a foreign exchange loss of $30,000. This results in a net increase of $1,300,000 in Retained Earnings that is balanced by an equal increase in Cash over the two-year period.

One criticism of the accrual approach is that it leads to a violation of conservatism when an unrealized foreign exchange gain arises at the balance sheet date. In fact, this is one of only two situations in U.S. GAAP in which it is acceptable to recognize an unrealized gain in income. (The other situation relates to trading marketable securities reported at fair value.)

SFAS 52 requires restatement at the balance sheet date of all foreign currency assets and liabilities carried on a company’s books. In addition to foreign currency payables and receivables arising from import and export transactions, companies might have dividends receivable from foreign subsidiaries, loans payable to foreign lenders, or lease payments receivable from foreign customers that are denominated in a foreign currency and therefore must be restated at the balance sheet date.

Each of these foreign currency denominated assets and liabilities is exposed to foreign exchange risk; therefore, fluctuation in the exchange rate results in foreign exchange gains and losses.

Many U.S. companies report foreign exchange gains and losses on the income statement in a line item often titled Other Income (Expense). Companies include other incidental gains and losses such as gains and losses on sales of assets in this line item as well. SFAS 52 requires companies to disclose the magnitude of foreign exchange gains and losses if material.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For example, in the Notes to Financial Statements in its 2005 annual report, Merck indicated that the income statement item Other (Income) Expense, Net included exchange gains of $16.1 million, $18.4 million, and $28.4 million in 2005,2004, and 2003, respectively.